On November 1, 1755, the city of Lisbon, in Portugal, it was hit by a earthquake of large dimensions. The destruction of the city was almost complete and the reconstruction went on for centuries. The reconstruction project was headed by Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, later known as marquis of pombal. Until today this occurrence is considered one of the greatest natural tragedies that hit Portugal.

The long-term impacts of this earthquake in Portugal were numerous. In politics, the earthquake consolidated Carvalho e Melo's position as secretary of state (head of state) of Portugal. The reconstruction also gave another face to the Portuguese capital, as the reconstruction was carried out in what became known as pombaline style. In addition, the Lisbon earthquake contributed to consolidate studies in the area of seismology.

Also access: Discover the history of the European who reported his trips to Brazil in the 16th century

Disaster

Lisbon in the 18th century was a city with the air of a medieval city, full of small, winding and dirty streets. The earthquake that hit it in 1755 occurred on November 1st, on a sunny morning. Reports say that, around 9:30 am, the city was shaken by a major earthquake.

The effect of the earthquake in a city in this condition was devastating, and reports say that the tremors extended for up to seven minutes, although there are reports to suggest that it may have extended for 15 minutes. O epicenter this earthquake was about 200 km to 300 km from Lisbon, more precisely to the southwest of mainland Portugal, in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Specialists in the field, even today, cannot precisely pinpoint the epicenter of this earthquake.

There is a theory that suggests that the first tremor happened in this area mentioned above and that a second tremor would have happened at the mouth of the Tagus River, but the most accepted theory suggests that there was no such tremor at the mouth of the Tagus. Current studies estimate that the 1755 quake reached 9 degrees on the Richter scale (the scale goes up to 10).

The magnitude of this earthquake contributed to the total destruction of the city. Many people in despair and fleeing the landslides and fires that hit other parts of the city fled to downtown Lisbon. There, these people were hit a tsunami that affected the entire region.

Thus, many of those who did not die in landslides and fires died as a result of the tsunami that flooded this part of Lisbon. Regarding the earthquake, historian João Lúcio de Azevedo narrated the following:

On the altars the images oscillate; the walls dance; beams and columns are unsoldered; the walls crumble with the bald sound of crumbling limestone and crushed human bodies; on the ground where the dead rest, the pits are engulfed, to engulf the living […]. The whole horror of hell in woes and torments. Disorderly escape with fatal accidents, and I keep stumbling over rocks and corpses […]. everywhere ruins|1|.

Among the landslides, the fire that consumed the city and the waves brought by the tsunami that flooded downtown Lisbon, specialists point to a high number of deaths. At the time, Lisbon had about 200,000 inhabitants and the number of deaths varies a lot, as there are those who point to around 10,000 dead, while others suggest more than 50 thousand dead in the disaster.

In addition to human lives, the material destruction was huge. The Royal Library was destroyed with more than 70,000 volumes of items stored there. The Tejo Opera House, inaugurated that year, was destroyed and the destruction of 35 churches, 55 palaces were listed and throughout the city it is believed that around 10,000 buildings were reduced to ruins.

Also access: Discover the war caused by the dispute over territories in colonial Brazil

Lisbon Reconstruction

Emergency actions after the earthquake were taken immediately through the energetic action of Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, future Marquis of Pombal. The actions taken on that occasion are understood as the first emergency action taken by the Portuguese State. The city's reconstruction works continued until the mid-19th century.

The first major action taken was to prevent the spread of disease and, thus, it was necessary to bury the dead. Most of the bodies were incinerated with the gigantic fires that spread across Lisbon, but many stayed below the ruins. To get rid of the bodies, the dead were buried in mass graves and many were cast into the sea with weights attached to make them sink.

One step taken to contain the proliferation of chaos brought about by the earthquake was to avoid the withdrawals. This was even part of a list of fourteen measures adopted by order of Carvalho e Melo. Those caught looting some house were hanged by the troops of the Kingdom.

The buildings that received priority in the reconstruction were the Churches – a fact that demonstrates the high degree of devotion to Catholicism in Portuguese society. Churches were the only buildings that had the right to innovation in the façade. All other buildings that were rebuilt had strict guidelines to be followed, with a fine provided for in case of non-compliance.

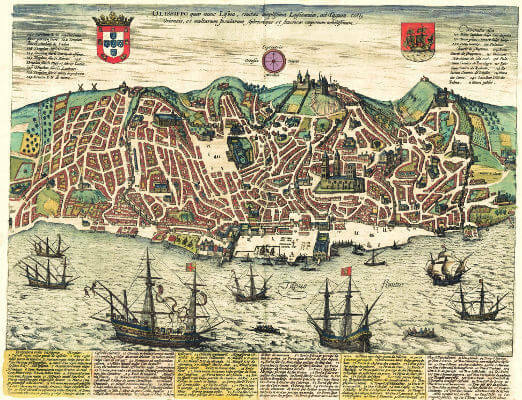

Map of Lisbon from 1598 shows the outline of the city's streets. The Lisbon before the earthquake was disorganized and had narrow, winding streets.**

The city of Lisbon was remodeled during the rebuilding process. The old medieval city, full of small, crooked streets and alleys was replaced by a Pombaline style with linear and wide streets and the facades of the buildings, as mentioned, followed guidelines determined by the State. The new architectural project and the reconstruction of the city were in charge of Carlos Mardel, Manuel da Maia and Eugênio dos Santos.

The Pombaline style determined linear and wide streets for Lisbon and the structure of the buildings' facades was predetermined by the government.

Downtown Lisbon, the most destroyed area, was known as Low Pombaline and received a great innovation for the time: the designed buildings received an anti-seismic structure. This structure became known as “pombaline cage”. This technique consisted of incorporating a wooden structure along the masonry walls.

The earthquake had a big impact on the Portuguese economy and the reconstruction needed to be financed in some way. Thus, Carvalho e Melo determined the increase in taxes in mining zones in the region of Minas Gerais. This action, in the long run, contributed to increasing the colonists' dissatisfaction with Portugal.

read more: Meet the character who symbolized dissatisfaction with Portugal in the 18th century

Repercussion of the disaster

Convento do Carmo is one of the great symbols of the destruction caused in Lisbon in the 1755 earthquake.

The Lisbon earthquake of 1755 had great international repercussion. Historians claim that, after the city's destruction, countless people from other countries went to Portugal to observe and report the destruction that Portugal's capital had suffered. The earthquake influenced the thinking of countless intellectuals such as Voltaire and Kant.

The Portuguese king – d. José I – started to suffer the rest of his days with claustrophobia. He survived the disaster, because at the time of the earthquake he was on the outskirts of Lisbon. The sight of destruction and reports of thousands of people buried dead made the king fearful of living indoors.

D. José I was king of Portugal until 1777 and until the end of his days he lived in a tent complex built in a Lisbon site called Alto da Ajuda. This location was chosen because it is high and has suffered little destruction and the tents built there became known as Royal Help Tent. This complex existed until the end of the 18th century, when a fire destroyed it.

In popular culture, the earthquake caused many to see the disaster as divine punishment and the case of Gabriel Malagrida is well known. Malagrida was a Jesuit priest and published a pamphlet treating the earthquake as a punishment from God. He was eventually denounced in the Inquisition, accused of heresy, and burned to death in 1761.

In another relevant aspect, the Lisbon earthquake contributed to the seismology development, the field of knowledge that studies earthquakes. That's because Carvalho e Melo sent inquiries to the parish priests in the region hit by the earthquake. The purpose of this survey, which had 13 questions, was to investigate the impacts of the earthquake.

Little was left of Lisbon from before the earthquake and everything you have today has been rescued by archeology. Buildings that remained standing and objects used by common people before the disaster are extremely important in reconstructing the events that happened with this natural disaster. One of the symbols of the earthquake is the ruins of the Carmo Convent, never rebuilt and which now houses a museum.

|1| AZEVEDO, José Lúcio de. The Marquis of Pombal and his times. Annuario do Brasil, Seara Nova, Portuguese Renaissance: Rio de Janeiro, Lisbon, Porto, 1922, p. 142.

*Image credits: commons

**Image credits: commons

By Daniel Neves

Graduated in History

Source: Brazil School - https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/historiag/terremoto-lisboa-1755.htm