THE law of the free womb was approved in September 28, 1871 and determined that the children of slaves born after the promulgation of the law would be considered free. The law still determined how this freedom would take place and even provided for compensation for the slave master in a certain scenario.

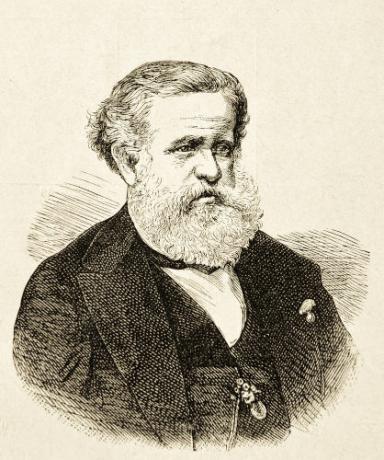

She is considered one of the abolitionist laws which were approved from 1850 onwards. It was part of the idea of carrying out a transition to abolition that would be slow and gradual so as not to generate economic impacts for the large farmers and not to generate revolt and social disorder. The bill for this law came from the Viscount of Rio Branco.

Accessalso: Did abolition solve the problem experienced by blacks in Brazil?

Context

THE abolitionist question it was one of the most heated discussions in Brazilian society in the 19th century. After the promulgation of the Eusébio de Queirós Law, in 1850, the political debate in that decade was dominated by the actions to be taken to definitively end the slave trade. The Brazilian government took affirmative action to suppress the traffic, and the last known slave ship tried to land Africans in Brazil in 1856.

The 1860s then turned to other debates regarding the slavery, and these discussions revolved around ways to abolish it. But what was behind these ideas to abolish slave labor?

First, it is important to identify that slave traders, mainly from the Southeast, still resisted these ideas. However, a certain political climate was beginning to emerge in this regard. The proposals that started to appear still brought the idea of promoting a abolition gradually, that did not generate heavy losses for the large farmers. The idea of gradual change was also aimed at maintaining social order.

It is also worth noting that, on the international scene, there was still a certain role of england in taking a stand for the abolition of slave labor in Brazil. Furthermore, the 1850s and 1860s were marked by initiatives abroad that moved in this direction. Portugal abolished slavery in its colonies in 1858, the US abolished slave labor in 1865, the Netherlands carried out the abolition of Suriname in 1863, the Russians ended serfdom in 1861, etc.

At that moment, only the Brazil and two Spanish colonies (Cuba and Puerto Rico) still used slave labor and in them there were already proposals for reforms or the abolition of slavery. Finally, Brazil still suffered from constraints in Paraguay War for being the only nation that still kept slaves. This isolation in the issue of slave labor was a stain on the country's international image.

Against this backdrop, many began to advocate this aforementioned gradual transition. This is because - it was argued at the time -, if abolition were carried out immediately, the country's economy would suffer a terrible impact., as abolition would deregulate production, and compensation paid to large farmers would deplete the national coffers.

Many planters criticized that this debate was being raised to the political level because it would serve as a motivation for slave rebellions. Many even believe that slave rebellions influenced this debate, but historian José Murilo de Carvalho claims that, in In the matter of Ventre Livre, the slave revolts had no influence because in that decade (1860) there were no movements of this type significant.

At slave revolts, however, served as an argument for defenders that a debate about abolition, even if gradual, should take place. They claimed that the abolition of slave labor should happen slowly and gradually through reformism, because if this did not happen, the slaves would rebel and we would have in Brazil a scenario similar to what happened in Haiti or even in the United States, where the issue of slave labor resulted in civil war.

readmore: Slave trafficking, the activity responsible for bringing millions of Africans to Brazil

proposal for reforms

It was this scenario that paved the way for a reform to take place. The first step towards this was taken by the emperor. In 1865, Dom Pedro II requested the José Antônio Pimenta Bueno a study that debated proposals to promote the abolition of slave labor in Brazil. The emperor was one of those who defended the reformist path to carry out this slow and gradual abolition.

Pimenta Bueno carried out this study, delivering to the emperor five different proposals in 1866. The emperor sent them to the Council of State, presided over by the Marquis of Olinda, but the agenda was not accepted. The following year, the agenda was again taken to the Council of State, and Pimenta Bueno's proposal was received in a divided manner.

Pimenta Bueno had proposed that the children of slave mothers would be freed at age 16, for girls, and at 21, for boys. However, his proposal noadvanced because of the scenario that Brazil was experiencing. Parliamentarians argued that this type of reform should only be raised after the Paraguayan War was over, and the idea remained shelved until 1871.

Still, the abolitionist debate has not lost steam. The emperor made pronouncements in 1867 and 1868 in favor of the question of abolition and there were some proposals on abolition suggested by deputies. In 1869, a law was passed banning slave auctions and that couples were separated, as well as the separation of children under fifteen from their parents was also banned.|1|.

In 1870, the Paraguayan War ended, which paved the way for this debate to be rescued. The “free womb” agenda returned to the political scene, when the Viscount of Rio Branco sent a proposal that defended the emancipation of the children of slaves. This proposal was based on what had been put forward by Pimenta Bueno and similar measures that had been implemented in places like Cuba. However, it was met with a lot of resistance, and the Viscount came under fire on the grounds that the argument he brought up could motivate slave rebellions in the country. Historian Boris Faust claims that this proposal was an initiative of the emperor and his advisers to guarantee greater loyalty from the slaves and prevent revolts from happening.|2|.

Accessalso: How was the life of ex-slaves after the Golden Law?

law of the free womb

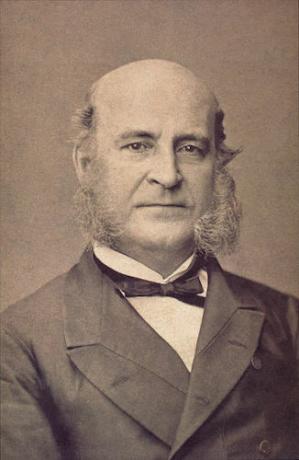

The bill proposed by the Viscount was debated and approved by the deputies. Boris Fausto says they were 51 votes for your approval and 36 against. Most of the votes in favor came from deputies from the Northeast, and the votes against came — the majority — from the South and Southeast, an indication of the differences in interest of the two regions.|3|. José Murilo de Carvalho presents the same scenario, but says that the vote had 61 votes in favor of the law and 35 votes against|4|.

![The Free Womb Law was enacted on September 28, 1871, freeing all children of slaves born after that date.[2]](/f/7e69ac49cfed9bb11ea763aa845271de.jpg)

The Free Womb Law was approved and entered into force on September 28, 1871. Through it, a fund was created to pay compensation for the freedom of the children of slaves. The scenario that the law presented was the following: slaves born from that date would be considered free, but they would be under the tutelage of their mother's lord, achieving their emancipation full when:

- reached 8 years of age (if they were freed at that age, the slave master would receive an indemnity);

- turn 21 years of age (release in this case was mandatory, and the slave master would not be compensated).

The indemnity provided for by law was 600 thousand réis, with a 6% annual readjustment within a maximum period of 30 years. The reality is that few slave masters turned over their female slaves' children at the age of 8 because it was more profitable to exploit their labor until they turned 21.

The law also obliged the slave master to maintain a registrationof your slaves. For this, a registry was created for these enrollments to take place. Slaves who were not duly registered in this registration would be considered free after one year of enactment of the law. This had many negative repercussions (for slave owners), as we shall see, but it worked as a legalization of slaves who had illegally entered Brazil after 1831.

Another important mechanism of the law was the ensure the release of slaves who suffered excessive abuse.. Slave masters were also obliged to free their slaves if they had the amount to indemnify their masters. These points of the law were openly explored by the abolitionist movement in the following years, he hired lawyers to guarantee the freedom of slaves.

Historian Joseli Maria Nunes Mendonça says that the abolitionist movement searched the records for irregularities to go to court against slave masters and provided legal support for slaves who found it difficult to pay for their manumission|5|. These were found ways to fight slavery that were very popular in the 1880s.

The law, however, was of characterconservative and demonstrated a willingness to maintain slavery for a while longer in Brazil. Historian Christiane Laidler also states that the way the law was drafted showed a great concern to not leave loopholes that could undermine the authority of slaveholders.|6|.

In any case, slavery had its days numbered in Brazil. In the 1880s, the pressure to end slavery was very great, and the abolition was enacted on May 13, 1888.

Grades

|1| MENDONÇA, Joseli Maria Nunes. Emancipationist legislation, 1871 and 1885. In.: SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz and GOMES, Flávio (eds.). Dictionary of slavery and freedom. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2018, p. 279.

|2| FAUSTO, Boris. Concise history of Brazil. São Paulo: Edusp, 2018, p. 122.

|3| Idem, p. 122.

|4| CARVALHO, José Murilo de. Building order: the imperial political elite. Shadow theater: imperial policy. Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Civilization, 2008, p. 310.

|5| MENDONÇA, Joseli Maria Nunes. Emancipationist legislation, 1871 and 1885. In.: SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz and GOMES, Flávio (eds.). Dictionary of slavery and freedom. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2018, p. 281-282.

|6| LAIDLER, Christiane. The Free Womb Law: interests and disputes around the “gradual abolition” project. To access, click on here.

Image credits

[1] commons

[2] National Archive of Brazil