it is understood by black literature the literary production whose subject of the writing is the black himself. It is from the subjectivity of black men and women, their experiences and their point of view that the narratives and poems thus classified.

It is important to emphasize that the literature black emerged as a direct expression of black subjectivity in countries culturally dominated by white power – mainly those who received the African diasporas, forced immigrations by the regime of the slave trade. This is the case in Brazil, for example.

The so-called official or canonical Brazilian literature, that is, that which corresponds to “classic” books, included in school curricula, reflects this paradigm of white cultural domination: is overwhelmingly written by whites portraying white characters.

The presence of black characters is always mediated by this racial distance and generally reproduces stereotypes: is the hypersexualized mulatto, the rogue, the victimized black, etc. This is the case of the black characters of Monteiro Lobato, for example, portrayed as servants without family (Tia Anastácia and Tio Bento), and apt to trickery as a natural factor (such as Saci-Pererê, a young man with no family ties who lives deceiving people from the place).

Thus, it is through black literature that the black and black characters and authors regain their integrity and its totality as human beings, breaking the vicious circle of racism institutionalized, ingrained in literary practice until then.

“Discrimination is present in the act of cultural production, including literary production. When the writer produces his text, he manipulates his memory collection where his prejudices reside. This is how a vicious circle takes place that feeds existing prejudices. The breaks in this circle have been carried out mainly by its own victims and by those who do not refuse to reflect deeply on race relations in Brazil”. |1|

![Cadernos Negros was created in order to compile and disseminate productions by black authors.[1]](/f/10c11a88879cdec93983fee79db344cd.jpg)

Origins: brief historical overview

The concept of black literature was consolidated in the mid-twentieth century, with the emergence and strengthening of black movements. Researcher Maria Nazareth Soares Fonseca points out that the genesis of black literary manifestations in quantity took place in the 1920s, with the so-called North American Black Renaissance, whose strands – BlackRenaissance, newBlack and HarlemRenaissance – rescued the links with the African continent, despised the values of the American white middle class and produced writings that constituted important instruments of denunciation of social segregation, as well as were directed to the struggle for civil rights of the black people.

According to Fonseca, this effervescent literary production was responsible for the affirmation of a awareness of being black, which later spread to other movements in Europe, the Caribbean, the Antilles and several other regions of colonized Africa.

It is important to emphasize that there is various literary trends within the concept of black literature. The characteristics change according to the country and the historical context in which the text is produced, so that the literature produced in the The beginning of the 20th century in the United States was different from that produced in Cuba (the so-called Negrismo Crioulo), which in turn differed from the publications of the Negritude movement, born in Paris, in the 1930s, as well as the black-Brazilian production had its own peculiarities, because the experience of being black in each of these territories is also diverse..

Although the concept of black literature only appeared in the 20th century, literary production made by blacks and addressing the black issue exists in Brazil since the 19th century, even before the end of the slave trade. It is the case of the few remembered (and abolitionists) Luiz Gama and Maria Firmina dos Reis, the first black novelist in Latin America and certainly the first female abolitionist author of the Portuguese language.

This is also the case for the famous Cruz e Sousa, icon of symbolist movement, of pre-modernLima Barreto and the greatest writer of Brazilian literature, Machado de Assis – The latter, constantly whitened by the media and publishers, to the point that many people were unaware that he was black.

More than three centuries of slavery normalized, in Brazil, the complete exclusion of the black population from citizen participation and its incorporation into official means of culture. Resisting on the fringes of this system, the black intelligentsia founded, in 1833, the newspaper the colored man, an abolitionist publication, one among several that manifested themselves in an increasing number throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, claiming guidelines that other media vehicles do not contemplated.

THE black press, in fact, is a cornerstone of the Brazilian press, so that the Brazilian Press Association (ABI) itself was founded by a black writer, Gustavo de Lacerda.

Know more:Three great black Brazilian abolitionists

black notebooks

An important milestone for the consolidation of black literature in Brazil was the emergence ofblack notebooks, poetry and prose anthology, first released in 1978. Born of the Unified Black Movement against Racial Discrimination – which later became simply MNU (Unified Black Movement) -, one of the various social instruments of political engagement of the era. You notebooks emerged mainly in favor of aself-recognition, political awareness and fight so that the black population had access to education and cultural goods.

THE first edition, formatted in pocket size and paid for by the eight poets that figured in it, received a great release, circulated in a few bookstores and also from hand to hand. Since then, one volume per year of the collection was released, whose editing is done by Quilombtoje, a group of writers committed to the dissemination and circulation of black literary production in Brazil.

“The day Brazilian literature critics are more attentive to writing the history of Brazilian literature, whether they like it or not, they will incorporate the history of the Quilombhoje group. It has to be incorporated. In the area of Brazilian literature as a whole, it is the only group that [...] has had an uninterrupted publication for 33 years. [...] I think that when historians, critics who have a broader view of literature emerge, it will be incorporated. This is the debt that Brazilian literature owes to the Quilombhoje group.” |2|

It was in the mid-1970s that the young black people began to occupy the universities in large numbers - even so constituting an exception in the face of the black population as a whole, which continued to be spatially excluded, as it constantly pushed to the peripheries from the housing programs of governments and municipalities, in addition to being also economically and culturally.

“That young black man arriving at university and not finding representations of his people in literature, in historical and sociological studies, asks himself: why? Until then, there was the image - common sense - that black people did not produce literature and knowledge [...]" |3|

Read more:The myth of racial democracy at the service of veiled racism in Brazil

Voices of Black Brazilian Literature

There are many exponents of black literature in Brazil today. Below, you will find a brief list of some of the best known authors, in order of birth, with a sample excerpt of their work.

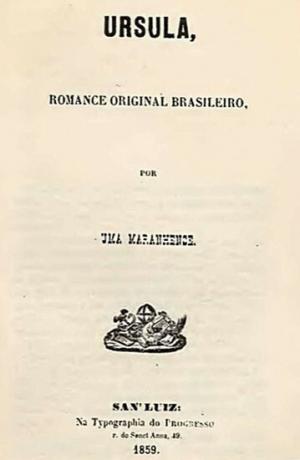

Maria Firmina dos Reis (São Luís – MA, 1822 – Guimarães – MA, 1917)

First woman to publish a novel in Brazil, the work of Maria Firmina dos Reis was a precursor of Brazilian abolitionist literature. Signed with the pseudonym "uma maranhense", Ursula was released in 1859.

The author, daughter of a black father and a white mother, was raised in her maternal aunt's house, in direct contact with literature from childhood. In addition to being a writer, Maria Firmina dos Reis was also a teacher and even taught mixed classrooms – boys and girls, whites and blacks, all in the same class – a great innovation in the 19th century, and also a confrontation with institutions patriarchal and slavers of the time.

“I and three hundred other companions of misfortune and captivity were thrust into the narrow and tainted hold of a ship. Thirty days of cruel torment, and the absolute lack of everything that is most necessary for life, we spent in this grave until we approached the Brazilian beaches. to fit the human merchandise in the basement we went tied up standing and so that there would be no fear of revolt, chained like the ferocious animals of our forests, which take themselves to the playground of the potentates of Europe. They gave us water that was filthy, rotten and given with stinginess, bad food and even more dirty: we saw many companions die beside us for want of air, food and water. It is horrible to remember that human beings treat their fellow men like this and that it does not give them the conscience of taking them to the grave asphyxiated and hungry!”

(Excerpt from the novel Ursula)

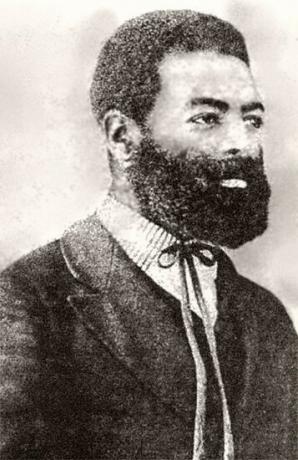

Luiz Gama (Salvador – BA, 1830 – São Paulo – SP, 1882)

great abolitionist leader, Luiz Gama was the son of a Portuguese father and Luiza Mahin, a black woman accused of being one of the leaders of the Malês revolt, a great slave uprising that took place in Salvador in 1835. Sold by father at age 10, he was a domestic slave until he was 18 years old, when he managed to prove that, being educated and the son of a free woman, he could not be captive. He joined the Public Force of the Province of São Paulo and later became a clerk at the Police Secretariat, where he had access to the police officer's library.

self-taught, became renowned lawyer, acting in the courts for the release of several blacks illegally held in captivity or accused of crimes against you. He also gave conferences and wrote controversial articles in which raised the banner of abolitionism and he directly struggled against society's whitening ideals. He published poems under the pseudonym “Afro”, “Getulino” or “Barrabás”, and released his first book in 1859, a collection of satirical verses named after him. Getulino's First Burlesque Trovas.

So the fettered slave sings.

Tibulum

Sing, sing Coleirinho,

Sing, sing, evil breaks;

Sing, drown so much hurt

In that voice of broken pain;

cry slave in the cage

Tender wife, your little son,

Who, fatherless, in the wild nest

There it was without you, without life.

When the purple dawn came

Meek and gentle, beyond the hills,

Of gold bordering the horizons,

Shading the vague curls,

— Along with the son, the sweet wife

Sweetly,

And in the sunlight you bathed

Fine feathers — elsewhere.

Today, sad no longer trills,

As in the past on palm trees;

Today, slave, in the manor houses

The bliss does not lull you;

Don't even marry your chirps

The moan of white drops

— Through the black bald rocks —

From the cascade that slides.

The tender son doesn't kiss you,

The mild source does not inspire you,

Not even from the moon the serene light

Come your silver irons.

Only shadows loaded,

From the cage to the perch

Comes the captivity tredo,

Grief and tears wake up.

Sing, sing Coleirinho,

Sing, sing, evil breaks;

Sing, drown so much hurt

In that voice of broken pain;

cry slave in the cage

Tender wife, your little son,

Who, fatherless, in the wild nest

There it was without you, without life.

(Getulino's first burlesque ballads)

Solano Trindade (Recife - PE, 1908 - Rio de Janeiro - RJ, 1974)

Francisco Solano Trindade was poet, activist, folklorist, actor, playwright and filmmaker. Founder of the Frente Negra Pernambucana and the Centro de Cultura Afro-Brasileira in the 1930s, he was a precursor of the black movement in Brazil. Afterwards, living in Rio de Janeiro, he founded, in Caxias, in 1950, the Teatro Popular Brasileiro (TPB), whose cast it was made up of workers, students and maids, and whose shows were staged inside and outside the Brazil.

In 1960, he moved to Embu, a city in the south of the capital of São Paulo, and its perennial and intense cultural ebullition transforms the territory, attracting artists and developing art and crafts locations. The municipality is now called Embu das Artes, and is a tourist attraction in the region. Solano Trindade has published 9 works and bears the epithet of poet of the people and of the black, for its militant emphasis on the popularization of art and the rescue of black Brazilian identity.

![Solano Trindade brings in his trajectory the important achievement of being one of the forerunners of the Black Movement in Brazil. [2]](/f/a06defc3bc6565bf7ffc5bb0a17089c7.jpg)

I'm black

Dione Silva

I'm black

my grandparents were burned

by the sun of africa

my soul received the baptism of the drums

atabaques, gongh and agogôs

I was told that my grandparents

came from Loanda

as a low-priced commodity

they planted sugarcane for the lord of the new mill

and founded the first Maracatu.

then my grandfather fought

like a darn in the lands of Zumbi

How brave was he?

In capoeira or the knife

wrote did not read

the stick ate

It wasn't a father John

humble and meek.

even grandma

it wasn't a joke

in the Malês war

she stood out.

in my soul was

the samba

the drumming

the swing

and the desire for liberation.

(in the people's poet, 1999)

See too:November 20 - Black Consciousness Day

Carolina Maria de Jesus (Sacramento – MG, 1914 – São Paulo – SP, 1977)

First black Brazilian author to meet fame in the publishing world, Carolina Mary of Jesus had little access to the basic resources of life in society. She only attended the first two years of elementary school and lived a life marked by poverty.

She kept diaries and notebooks where she wrote poems and took notes on the exhausting reality that imposed itself around her. It was discovered by a journalist she when she lived in the Canindé favela, in São Paulo, living as a garbage collector.

![Carolina Maria de Jesus was the first black Brazilian author to gain fame from her publications. [2]](/f/4e2bf0f130f7e979b941174900cc8df7.jpg)

It is mainly about this period that the book is about Eviction Room: Diary of a Favela, the best known of her publications, where the author highlights the marginalized situation in which she lived, fighting against hunger, dirt, racism among favela residents and city passersby, among others ailments.

The work sold more than 10,000 copies in the week of its release, and 100,000 during the year. While still alive, Carolina published three more works, and another four were released after her death.

“May 13th. Today dawned raining. It's a nice day for me. It's Abolition Day. Day we commemorate the liberation of slaves.

...In prisons the blacks were the scapegoats. But whites are now more cultured. And he doesn't treat us with contempt. May God enlighten whites so that blacks may be happy.

It keeps raining. And I only have beans and salt. The rain is heavy. Still, I sent the boys to school. I'm writing until the rain passes, so I can go to Senhor Manuel to sell the irons. With the money from the irons, I will buy rice and sausage. The rain passed a little. I'll go out. ...I feel so sorry for my children. When they see the things to eat they cry:

– Long live mom!

The demonstration pleases me. But I've already lost the habit of smiling. Ten minutes later they want more food. I sent João to ask Dona Ida for a little fat. She didn't. I sent you a note like this:

– “Dona Ida, I ask if you can get me some fat, so I can make soup for the boys. Today it rained and I couldn't pick up paper. Thank you, Carolina”.

...It rained, it got cold. It's winter that comes. And in winter we eat more. Vera started asking for food. And I didn't. It was the rerun of the show. I was with two cruises. I intended to buy some flour to make a turn. I went to ask Dona Alice for some lard. She gave me lard and rice. It was 9 pm when we ate.

And so on May 13, 1958 I struggled against current slavery – hunger!”

(Eviction Room: Diary of a Favela)

Maria of Conceição Evaristo de Brito (Belo Horizonte – MG, 1946)

Professor, researcher, poet, storyteller and novelist, Conceição Evaristo is one of Brazil's most celebrated contemporary authors. She debuted in literature in 1990, promoting her poetry in the black notebooks.

PhD in Comparative Literature from the Universidade Federal Fluminense, she dedicates her research to the critical production of black authors – in Brazil and also in Angola. She released her first novel, Poncia Vicencio, in 2003, and since then her work has been the object of research in Brazil and abroad, with five titles translated into English and French. Her work elects the black woman as the main protagonist, mixing fiction and reality, in a concept that the author called “writings”.

![Conceição Evaristo is a great name in contemporary black literature. [3]](/f/e1f19911b9ee8532b3fbda4b61a0a9e8.jpg)

my rosary

My rosary is made of black and magical beads.

In the beads of my rosary I sing Mama Oxum and I speak

Our Fathers, Hail Marys.

From my rosary I hear the distant drums of the

my people

and encounter in the sleeping memory

the May prayers of my childhood.

The Lady's coronations, where the black girls,

despite the desire to crown the Queen,

had to be content with standing at the foot of the altar

throwing flowers.

My rosary beads turned calluses

on my hands,

because they are accounts of work on the land, in factories,

in homes, in schools, on the streets, in the world.

My rosary beads are living beads.

(Someone said that one day life is a prayer,

I would say however that there are blasphemous lives).

In the beads of my rosary I weave bloated

dreams of hope.

In my rosary beads I see hidden faces

by visible and invisible grids

and I rock the pain of the losing fight on the bills

of my rosary.

In the beads of my rosary I sing, I scream, I keep silent.

From my rosary I feel the bubbling of hunger

In the stomach, heart and empty heads.

When I thrash my rosary beads,

I speak of myself in another name.

And I dream in my rosary beads places, people,

lives that little by little I discover real.

I go back and forth through my rosary beads,

which are stones marking my path-body.

And on this floor of stone beads,

my rosary turns into ink,

guide my finger,

poetry insinuates me.

And after macerating my rosary,

I find myself here myself

and I discover that my name is still Maria.

(Poems of Remembrance and Other Movements, 2006)

Cuti (Ourinhos - SP, 1951)

Luiz Silva, known by the pseudonym Cuti, is one of the most outstanding names of the Brazilian black intelligentsia. Master and Doctor in Letters from Unicamp, Cuti is a researcher of black literary production in Brazil, in addition to being a poet, short story writer, playwright and activist.

He is one of the founders and maintainers of the publications. black notebooks and the NGO Quilombhoje Literatura. His work – fictional and non-fictional – is dedicated to denouncing Brazilian structural racism and rescuing black ancestry and the memory of the black movement.

His is the concept of black-Brazilian literature as opposed to an idea of Afro-descendant literature, pointing out how the remission to Africa further distances the Brazilian black subject from its history and experience. He also authored important studies on the work of Cruz e Sousa, Lima Barreto, Luiz Gama, Machado de Assis, among others.

![Negroesia is a poetic anthology that reflects on the place of black people in Brazilian society. [5]](/f/e64ba5e6dbf8f4c0ea22f14f8a622331.jpg)

broken

sometimes I'm the policeman I suspect

I ask for documents

and even in possession of them

I hold myself

and I hit myself

sometimes I'm the doorman

not letting me in on myself

unless

through the service door

sometimes i'm my own offense

the jury

the punishment that comes with the verdict

sometimes I'm the love that I turn my face

the broken

the backrest

the primitive solitude

I wrap myself in emptiness

sometimes the crumbs of what I dreamed and didn't eat

others I saw you with glazed eyes

trilling sadness

one day it was abolition that I threw myself into the

amazement

later a deposed emperor

the republic of concoctions in the heart

and then a constitution

that I enact myself at every moment

also the violence of an impulse

I turn inside out

with lime and plaster hits

I get to be

sometimes I make a point of not seeing myself

and clogged with their sight

I feel misery conceived as an eternal

beginning

close the circle

being the gesture I deny

the drip that I drink and I get drunk

the pointing finger

and I denounce

the point at which I surrender.

sometimes...

(Negroesia)

Elisa Lucinda dos Campos Gomes (Cariacica – ES, 1958)

Elisa Lucinda is journalist by training, but acts as an actress, poet and singer. Considered one of the artists of her generation who most popularizes the poetic word, she officially debuted in literature with the book of poems the similar (1995), which originated a play of the same name, in which the actress intersected the dramaturgical text with dialogues open to the public.

With more than twelve books published, including short stories and poems, Elisa Lucinda is also known for her several roles in Brazilian soap operas and films, as well as sound recordings of recited poems and songs.

![Elisa Lucinda accumulates in her career participations in theater, television drama, music and literature. [4]](/f/dc02af1c56808f9b42f9c519c5084d4c.jpg)

export mulatto

"But that denies beautiful

And still green eye

Eye of poison and sugar!

Come deny it, come be my excuse

Come on in here it still fits you

Come be my alibi, my beautiful conduct

Come, deny export, come my sugar loaf!

(I build a house for you but no one can know, do you understand my palm?)

my dizziness my bruised story

My confused memory, my football, do you understand my gelol?

Roll well my love, I'm your improvisation, your karaoke;

Come deny, without me having to do anything. Come without having to move

In me you forget tasks, slums, slave quarters, nothing will hurt anymore.

I smell sweet, my maculelê, come deny it, love me, color me

Come to be my folklore, come to be my thesis on nego malê.

Come, deny it, crush me, then I'll take you for us to samba.”

Imagine: I heard all this without calm and without pain.

This former foreman already arrested, I said: "Your delegate…"

And the marshal blinked.

I spoke with the judge, the judge insinuated himself and decreed a small penalty

with a special cell for being this intellectual white...

I said, “Your Judge, it's no use! Oppression, barbarity, genocide

none of that can be cured by screwing a dark one!"

O my highest law, stop screwing up

It won't be an unresolved blank

that will free a black woman:

This white blaze is doomed

because it's not like a pseudo-oppressed

that will ease your past.

Look here my lord:

I remember the slave quarters

and you remember the Big House

and let's sincerely write another story together

I say, I repeat and I don't lie:

Let's clear this truth out

why is not dancing samba

that I redeem you or believe you:

See if you stay away, don't invest, don't insist!

My disgust!

My cultural bait!

My can wash!

Why stop being racist, my love,

it's not eating a mulatto!

(the similar)

Cidinha da Silva (Belo Horizonte – MG, 1967)

Novelist, dramatist, short story writer, researcher, educator, cultural manager are some of the areas in which the artist and activist Cidinha da Silva works. Founder of Instituto Kuanza and for some time in charge of the presidency of GELEDÉS – Instituto da Mulher Negra, the author began her publications with texts aimed at the area of education, like the article in the book rap and education, rap is education (1999) and the chapter in Racism and anti-racism in education: rethinking our history (2001). She was also the organizer of the volume Affirmative Actions in Education: Brazilian Experiences (2003).

In literature, Cidinha debuted with the compilation Each Trident in its placeand other chronicles (2006), and since then it has published at least twelve other works, in the most diverse formats – short stories, chronicles, plays and children's books, in addition to several articles on race and gender relations published in Brazil and in other countries, such as Uruguay, Costa Rica, United States, Switzerland, Italy and England.

Melo of contradiction

The black boy was very sad and told the other boy who had presented medical certificates to the company to be fired. So he intended to pay off his first semester's college debt and shut down his tuition, to get back God knows when.

But this is the problem of every poor young person who studies at a private college, he doesn't have to be black to go through it. That's right, but it turns out that he works as a replenisher of goods in a monumental chain of drugstores in the city and he feels humiliated because the rule is that stockers ascend to the sales position (if they are good employees and he was) within a maximum period of eight months. He has already turned fifteen and all the (white) colleagues who joined him are already salespeople.

Naive, like every 23-year-old dreamer, he thought he would be promoted (rewarded) for passing the entrance exam at a good university and for taking a course related to his professional field. Oh nothing, the manager was insensitive and even said that soon, he would give up this idea of higher education, "a bourgeois thing".

He cried and punched his pillow thinking that the salesman's salary, plus commissions, it would allow you to pay at least five of the seven semester tuition, and the remaining two, the school. would negotiate.

He made another foray, this time to try to lessen his fatigue and transportation expenses. He asked for a transfer to a drugstore unit closest to the college, where no one wants to work, especially those who enjoy the status of working in a downtown store. He received another no. There, he had no choice but to piss off the manager to get fired. He couldn't resign because he would lose his unemployment insurance and then he wouldn't even be able to pay off the debt that plagued him.

Thankfully, the weekend ballads are approaching and with them the warmth of the white girls who think he's a cute, hot little nigga who takes his hat off. And they give him the illusion of being less black and discriminated against, as he appears as a basic little black in the wardrobe.

(Each Trident in its Place and other chronicles)

A-N-A Maria Gonçalves (Ibiá – MG, 1970)

An advertiser by training, Ana Maria Gonçalves left the profession to devote herself fully to literature. Novelist, short story writer and researcher, the author released her first book, Beside and on the sidelines of what you feel for me in 2002.

a color defect was published four years later, in 2006, and its narrative is inspired by the Luiza Mahin's story, a great black character in Brazilian history, heroine of the Revolta dos Malês, and her son, the poet Luiz Gama. The book, which recovers more than 90 years of Brazilian history, was awarded the Casa de las Américas Prize (Cuba), in addition to being elected one of the 10 best novels of the decade by the newspaper The globe.

Ana Maria Gonçalves also worked at foreign universities as a guest writer and was awarded by the Brazilian government, in 2013, with the commendation of the Order of Rio Branco, for national services of its actions anti-racists.

“The longboat carrying the priest was already approaching the ship, while the guards distributed some cloths between us, so that we would not go down naked to the ground, as they also did to the men in the Beach. I tied my cloth around my neck, like my grandmother used to do, and ran through the guards. Before any of them could stop me, I jumped into the sea. The water was hot, hotter than in Uidah, and I couldn't swim well. Then I remembered Iemanjá and asked her to protect me, to take me to earth. One of the guards fired a shot, but I soon heard shouting at him, probably not to lose a piece, as I had no way of escaping except for the island, where others were already waiting for me. Going to the island and running away from the priest was exactly what I wanted, to land using my name, the name that my grandmother and my mother had given me and with which they introduced me to the orixás and the voodoo."

(a color defect)

Image credits

[1] Quilombtoje/ Reproduction

[2] Public domain / National Archives Collection

[3] Paula75/commons

[4] Luis Gustavo Prado (Secom UnB) /commons

[5] Mazza Editions/ Reproduction

Grades

|1| CUTI. Black Brazilian Literature. São Paulo: Selo Negro, 2010, p. 25

|2| Conceição Evaristo in an interview with Bárbara Araújo Machado, in 2010

|3| COSTA, Aline. “A story that has just begun”. Black Notebooks – Three Decades, vol. 30, p. 23

by Luiza Brandino

Literature teacher

Source: Brazil School - https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/literatura/literatura-negra.htm