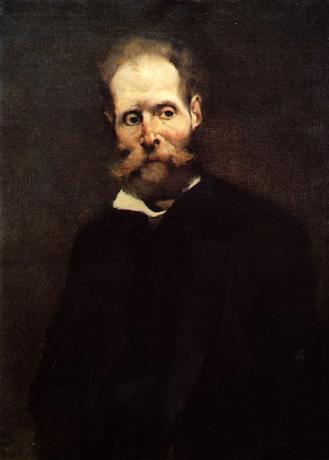

Antero de Quental he was born on April 18, 1842, in Ponta Delgada, on the Portuguese island of São Miguel. He studied law at Coimbra, but later worked as a typographer in France, which brought him closer to the reality of workers. Thus, in 1875, he was one of the founders of the Portuguese Socialist Party.

Belonging to the generation of 70, he participated in the famous intellectual debate known as the Coimbrã Question, and its text common sense and good taste was a big highlight in this discussion. despite being one of the introducers of rrealism in Portugal, the author, who committed suicide on September 11, 1891, produced works that also have romantic traits.

Read more: Realism in Brazil – characteristics and works of this aesthetic in Brazilian lands

Biography of Antero de Quental

Antero de Quental was born on April 18, 1842, in the city of Ponta Delgada, island of São Miguel, belonging to Portugal. At the age of 10, he began studying at António Feliciano de Castilho's school (1800-1875) in Lisbon. In the year he turned 16, he moved to Coimbra, where

did law school. In 1861 he published his first book of poetry — Antero's Sonnets.Upon finishing college, he lived in Lisbon and then in Paris. In the French city, he exercised the profession of typographer, in 1867. Back to Portugal, started to attend the Cenacle meetings, a group of intellectuals who discussed art, politics, science and customs. He became one of the main names in this group, which also had the presence of Eça de Queirós (1845-1900).

Do not stop now... There's more after the advertising ;)

Quental, in 1870, with Oliveira Martins (1845-1894), created the republic, the “newspaper of Portuguese democracy”. Five years later, he was one of the founders of the Portuguese Socialist Party and the Western Magazine, which sought to encourage the exchange of ideas between Portuguese and Spanish intellectuals.

With health problems, he spent time in treatment in France between 1878 and 1879. Back to Lisbon, ran for deputy for the Socialist Party. In addition, he adopted the girls Albertina and Beatriz, daughters of a deceased friend.

For the next 10 years, he lived with them in Vila do Conde. So if devoted, diligently, to his poetic production. Until, in 1890, he joined the short-lived Northern Patriotic League movement. The following year, he returned to live in his native land, where he decided to end his own life on September 11, 1891.

Read too: José Saramago – Portuguese author winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature

Coimbra issue

Coimbra issue was the name given to literary discussions among authors, on the one hand, defenders of realismand, on the other, of romanticism. These Portuguese intellectuals, in their dispute, used periodicals to defend their ideas through the publication of open letters, articles and poems, in the years 1865 and 1866.

Most of these writers attended the University of Coimbra, hence the origin of the name of the dispute. The leader of the romantics was António Feliciano de Castilho. The most powerful voice in opposition to this writer was, precisely, Antero de Quental, who published the scathing text Common sense and good taste: letter to the Excellency Mr. António Feliciano de Castilho.

To get an idea of the state of mind of these intellectuals, let's read, below, an excerpt from the end of this letter from Quental to Castilho:

“I still had a lot to say: but I fear, in the ardor of the speech, I lack respect for you. ex., to your white hair. I'm even careful that I've missed a phrase or two not as reverent and as flattering as I'd wished. But I really don't know how to say, without seeming to teach, certain elementary things to a sixty-year-old man; say them with my twenty-five! V. ex. he put up with me in time at his Colégio do Portico, I was still ten years old, and I confess that I owe to his great patience what little French I still know. [...]. But I see with disgust that we often have to deny the twenty-five years of worship of the authorities of the ten; and that knowing how to explain Telemachus well to children is not precisely enough to give the right to teach men what reason and taste are. [...]. It is for all these reasons that I regret from the bottom of my soul that I cannot confess, as I wished, to you. ex. neither admirer nor respectful.”

Quental and, by extension, his comrades attacked what they called "ultraromanticism". Thus, fought against the conservatism of the romantics. It was, therefore, the new generation, full of revolutionary ideas, that fought the old and outdated. As in any rupture, insults were inevitable, however delicately disguised.

Literary Characteristics of Antero de Quental

A member of the 70's generation, Quental produced works that present, contradictorily, romantic and realistic features. Therefore, despite being considered by some critics as a realist writer, it is correct to state that Antero de Quental was an author of transition between these two aesthetics.

THE romantic utopia is present in the poet's first works, which, sympathizer of the socialism, ended up resorting to sociopolitical criticism in his evolution as a writer. Furthermore, your sonnets, as a form, show signs of rationality. Some of his poems have romantic elements, such as melancholy, pessimism, morbidity, loving idealization and mysticism.

Works by Antero de Quental

![Cover of the book “Antero de Quental”, Best Poems collection, by Global Editora.[1]](/f/97c9657ca802ac54772553b563ea7440.jpg)

Antero's Sonnets (1861)

Beatriceand fiat lux (1863)

modern odes (1865)

common sense and good taste (1865)

The dignity of letters and official literature (1865)

letter defense andncyclic of swow santiquity Pius IX (1865)

Portugal before the Spanish Revolution (1868)

Causes of the decay of peninsular peoples (1871)

romantic springs (1872)

Considerations on the philosophy of Hstory thereiterary Pportuguese (1872)

poetry today (1881)

the complete sonnets (1886)

The philosophy of nonature of naturists (1886)

General trends in philosophy in the second half of the 19th century (1890)

rays of extinct light (1892)

See too: Star of a lifetime - compilation of poems by Manuel Bandeira

Antero de Quental's Sonnets

We will now analyze two sonnets by Antero de Quental. The first is “I don't know", in which O me lyric talk to an unknown god, which would be a “dreamed vision”. The poetic voice seeks to find this god on earth, characterized as a being of intense brightness, merciful, immortal, compared to a look of pity and a drop of honey; and finally, challenges this god to show himself in heaven if he really exists:

What mortal beauty resembles you,

O dreamy vision of this ardent soul,

That you reflect on me your great brilliance,

There, how over the sea does the sun shine?

The world is big — and this urge advises me

Looking for you on earth: and I, poor believer,

I'm looking for a forgiving God throughout the world,

But the Ara only finds you... naked and old...

It's not mortal what I adore about you.

What are you here? look of pity,

Drop of honey in a bowl of poisons...

Pure essence of the tears I cry

And dream of my dreams! if you are true,

Discover yourself, vision, in heaven at least!

That poem features decasyllable verses (10 poetic syllables) — a hallmark of realistic Parnassian poetry — but also traces of romanticism, such as: sentimentality, theocentrism, exclamations, reticence and excess of adjectives.

These same features can be seen in the sonnet "Aspiration”. In it the lyrical self does reference to the passage of days, which pass without pleasure and without pain. He affirms that life is beautiful and full of love, but there is an even greater beauty, the “eternal homeland”, that is, the afterlife, which the soul of the lyrical self wants to reach. However, as in the previous sonnet, he asks God for confirmation:

My days go slowly

No pleasure and no pain, and it even seems

That the inner focus already fades

And it falters with doubtful rays.

Life is beautiful and the years are beautiful,

And never in the breast lover love dies...

But if beauty appears here,

Soon another reminds of purer enjoyments.

My soul, O God! to other heavens aspires:

If a moment held her deadly beauty,

It is for the eternal homeland that he sighs...

But the feeling gives me the certainty,

Give it to me! and serene, although the pain hurts me,

I will always bless this sadness!

Phrases of Antero de Quental

Let's read, below, some sentences by Antero de Quental, taken from his famous text Common sense and good taste: letter to the Excellency Mr. António Feliciano de Castilho:

"The intelligence of the skilful, the prudent, the very clever is often blind because it lacks a very small thing—good faith."

"The pilot wants his eyes unveiled to read in the stars the path of the ship through the uncertain waves."

"The great modern geniuses are grotesque and despicable to the dull eyes of the banal Portuguese meter."

"Age does not make her gray hair, but maturity of ideas, flair and seriousness."

"The futility in an old man dislikes me as much as the gravity in a child."

Image credit

[1] Global Editorial Group (reproduction)

by Warley Souza

Literature teacher