Yellow-green movement or the school of tapir is how an ultranationalist literary current of Brazilian modernism became known. Its creators were the authors Cassiano Ricardo, Menotti del Picchia and Plínio Salgado. Emerged in 1926, the movement peaked in 1929, with the publication of the Manifesto nhengaçu verde-amarelo.

In addition to the nationalist tenor, the yellow-green movement was against academic art and European avant-garde movements. In this context, he produced works such as the novel The foreigner, by Plínio Salgado; the epic Martim Cerere, by Cassiano Ricardo; It is Republic of the United States of Brazil, poems by Menotti del Picchia.

Read too: Modern Art Week of 1922 — official landmark of modernism in Brazil

Topics of this article

- 1 - Summary about the green-yellow movement or the tapir school

- 2 - What was the yellow-green movement?

- 3 - Historical context of the yellow-green movement

- 4 - Green-and-yellow movement or tapir school?

- 5 - Characteristics of the yellow-green movement

- 6 - Who participated in the yellow-green movement?

- 7 - Main works of the yellow-green movement

- 8 - What did the Manifesto of the green-yellowism or the tapir school say?

Summary about the green-yellow movement or the school of the tapir

The green-yellow movement is part of the first phase of Brazilian modernism.

It emerged in 1926 and reached its peak in 1929, with the publication of the Manifesto of Verde-Amarelismo.

The movement is also called the tapir school, an animal symbol of this literary current.

Green-yellow presents boastful nationalism and criticizes academic art.

Its founders and main representatives are the writers Menotti del Picchia, Cassiano Ricardo and Plínio Salgado.

What was the yellow-green movement?

The yellow-green movement was part of the first phase of Brazilian modernism. so he officially appeared on July 25, 1926, in the newspaper São Paulo Mail. And its creators were the modernist writers Cassiano Ricardo, Plínio Salgado and Menotti del Picchia.

The movement reached its peak with the publication, on May 17, 1929, of the Manifesto nhengaçu Verde-Amarelo, also known as the Manifesto of Verde-Amarelismo or of the Tapir School, signed by the Anta Group. The manifesto was published in the newspaper São Paulo Mail.

That literary current defended the boastful, radical and conservative nationalism. Ideologically, it foreshadowed Integralism, a political movement of fascist nature. However, as well as the brazilwood movements It is anthropophagic, the green-yellow movement also valued indigenous primitivism.

Do not stop now... There's more after the publicity ;)

Historical context of the yellow-green movement

The Verde-Amarelo movement was consolidated in 1929 with the publication of the Manifesto nhengaçu Verde-Amarelo, or Manifesto of Verde-Amarelismo or the School of the Tapir. Such a modernist movement appeared on the eve of the Vargas Era, started in 1930. This period of Brazilian history was marked by authoritarianism and an approach to fascism, which appeared in Italy in 1919.

See too: Second phase of modernism in Brazil — art in the context of dictatorship and war

Yellow-green movement or tapir school?

The tapir was the symbol of the yellow-green movement. This is because the animal is part of the Tupi tradition, as a totem. For this reason, in 1927, the green-yellow movement, created a year earlier, came to be called the tapir school. Therefore, the green-yellow movement and the school of the tapir are one and the same.

It should be noted that this literary movement preceded (or foreshadowed) integralism or Brazilian Integralist Action. This far-right, fascist political movement was led by the writer Plínio Salgado. And it was founded in 1932, that is, after the creation of the yellow-green movement.

Characteristics of the yellow-green movement

Valorization of Brazilian primitivism.

Rejection of tradition with a European character.

boastful nationalism.

Antiacademicism.

Criticism of European avant-garde movements.

Analysis of the Brazilian reality.

Who participated in the yellow-green movement?

The main members of the movement are the authors:

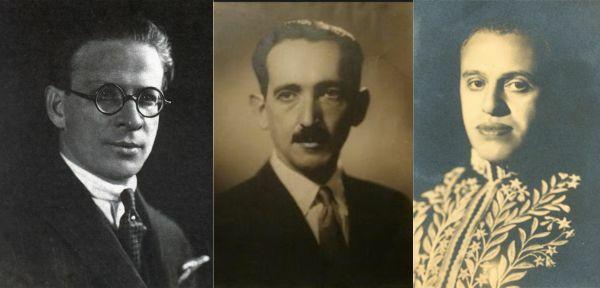

Menotti del Picchia (1892–1988);

Cassiano Ricardo (1895–1974);

Plínio Salgado (1895–1975).

Main works of the yellow-green movement

The foreigner (1926), novel by Plínio Salgado

The tapir and the curupira (1927), manifesto by Plínio Salgado

Martim Cerere (1928), epic poem by Cassiano Ricardo

Republic of the United States of Brazil (1928), poems by Menotti del Picchia

The Republic 3000 (1930), novel by Menotti del Picchia

Know more: Macunaíma — modernist novel that praises Brazilian cultural diversity

What did the Manifesto of the Verde-Amarelismo or the tapir school say?

The Manifesto nhengaçu verde-amarelo, or Manifesto do verde-amarelismo or the tapir school, was published in 1929. This document, the indigenous not considered as an independent people, but as a diluted part of the Brazilian miscegenation process:

The Tupis descended to be absorbed. To dilute themselves in the blood of new people. To live subjectively and transform the kindness of Brazilians and their great sense of humanity into a prodigious strength. Your totem is not carnivorous: Tapir. This is an animal that opens paths, and this seems to indicate the predestination of the Tupi people.

In this way, the Tupi would only exist “subjectively” in the “new people”, that is, the Brazilians. After all, as the manifesto says: “The whole history of this race corresponds [...] to a slow disappearance of objective forms and a growing appearance of national subjective forces.”

Like this, the manifesto does not see indigenous acculturation as something negative: “The Jesuit thought he had conquered the Tupi, and the Tupi had conquered the Jesuit religion for themselves.” And he considers an abstract influence of this people on Portuguese: “[...]; and the Portuguese was transformed, and rose with the physiognomy of a new nation against a metropolis: because the Tupi won within the soul and blood of the Portuguese”.

The idea that the Tupi made a contribution to the emergence of the race is evident in the manifesto. Brazilian, but from the acceptance of foreign rule: “The tapuia isolated itself in the jungle, to to live; and he was slain by the arquebuses and enemy arrows. The Tupi socialized without fear of death; and it was eternalized in the blood of our race. The Tapuia is dead, the Tupi is alive.”

there is no criticism to the colonization process, but the acceptance of the “civilizing” process as something positive:

Tupi nationalism is not intellectual. It's sentimental. And of practical action, without deviations from the historical current. It can accept the forms of civilization, but it imposes the essence of feeling, the radiant physiognomy of its soul. Feel Tupã, Taniandaré or Aricuta even through Catholicism. He has an instinctive horror of religious struggles, before which he smiles sincerely: what for?

In the manifesto, Tupi is part of Brazilian nationality, but only as one more member of the process of formation of the Brazilian people:

The Nation is a result of historical agents. The Indian, the black, the swordsman, the Jesuit, the drover, the poet, the farmer, the politician, the Dutch, the Portuguese, the Indian, the French, the rivers, the mountains, mining, the livestock, agriculture, the sun, immense leagues, the Southern Cross, coffee, French literature, English and American politics, the eight million kilometers square...

The subjective question of the Tupi, according to the manifesto, is related to the disappearance of this individual, so that the Tupi race would have subjectively survived in Brazilian culture. That way, the native is just a symbol, but disregarded as an independent people:

The tapir movement was based on this principle. The Indian was taken as a national symbol, precisely because he means the absence of prejudice. Among all the races that formed Brazil, the autochthonous was the only one that objectively disappeared. In a population of 34 million we do not count half a million savages. However, it is the only one of the races that subjectively exerts over all the others the destructive action of characterizing traits; [...]; it is the transforming race of races, and that is because it does not declare war, because it does not offer any of the others the vitalizing element of resistance.

The manifesto also presents an idealizing or denialist, given that does not recognize the existence of racial and religious prejudice in Brazil:

There are no racial prejudices among us. When it was May 13, there were blacks already occupying high positions in the country. And before, as after that, the children of foreigners from all backgrounds never saw their steps hampered.

We also do not know about religious prejudices. Our Catholicism is too tolerant, and so tolerant, that its extreme defenders accuse the Brazilian Church of being an organization without combative force (v. Jackson Figueiredo or Tristão de Athayde).

All the time, the manifesto repeats the fact that the indigenous are “subjectively” in the Brazilian people and reinforces the acceptance of the domination of this people:

Thus, the Indian is also a constant term in the Brazilian ethnic and social progression; but one term is not everything. He was already dominated, when the nationalist flag was waved among us, - the common denominator of the adventitious races. Putting it as the numerator would be decreasing it. Overlapping it will doom it to disappear. Because he still lives, subjectively, and will always live as an element of harmony among all those who, before disembarking in Santos, threw into the sea, like Zarathustra's corpse, the prejudices and philosophies of origin.

However, the tapir school group, which signed the manifesto, insists on talking about equality and freedom:

The “verdamarelo” group, whose rule is the full freedom of each one to be Brazilian as he wants and can; whose condition is that each one interprets his country and its people through himself, through his own instinctive determination; — the “verdamarelo” group, to the tyranny of ideological systematizations, responds with its manumission and the unhindered breadth of its Brazilian action. Our nationalism is one of affirmation, of collective collaboration, of equality of peoples and races, of freedom of thought, of belief in the predestination of Brazil in humanity, of faith in our value of building national.

image credits

[1] Wikimedia Commons (adapted)

Sources

ABAURRE, Maria Luiza M.; PONTARA, Marcela. Brazilian Literature: times, readers and readings. 3. ed. São Paulo: Editora Moderna, 2015.

CARVALHO, Alexandre Douglas Zaidan de. Fascism and populism between global history and political theory.Society and State, v. 36, no. 1, Jan./Apr. 2021.

CRUZ, Natalia dos Reis. The Vargas government and fascism: approximation and repression.Present Time Bulletin, no. 4, 2013.

PICCHIA, Menotti del et al. Green-yellow Nhengaçu (Manifesto of the green-yellowism or the school of the tapir). Available in: https://icaa.mfah.org/s/es/item/781033#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-2001%2C-1102%2C6551%2C3666.

REISS, Regina Weinfield. Integralism (Brazilian fascism in the 1930s).Business Administration Magazine, v. 14, no. 6, Dec. 1974.

ZEM EL-DINE, Lorenna Ribeiro. The soul and shape of Brazil: São Paulo modernism in yellow-green (1920s). 2017. 220 f. Thesis (Doctorate in History of Science and Health) – Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, 2017.

ZEM EL-DINE, Lorenna Ribeiro. Essay and interpretation of Brazil in yellow-green modernism (1926-1929).Historical Studies, Rio de Janeiro, vol. 32, no. 67, 2019.

By Warley Souza

Literature Teacher

Read the analysis of the book “Macunaíma”. Know its plot, characteristics and characters. Learn a little about the life of its author, Mário de Andrade.

Find out who the modernist writer Menotti del Picchia was. Get to know the main characteristics of his works and, in addition, read some of the author's sentences.

Learn more about Modernism in Brazil, its historical context, its European influences and proposed ruptures. Check out its stages, main works and artists.

Click here, find out what the anthropophagic movement was and find out what its main characteristics are.

Click here and understand what the pau-brasil movement was. Find out what its main characteristics are and find out who its participants were.

Understand how Brazilian racial disparities are reflected in literature and how canonical works portray black characters. Learn more about black literature!

Get to know the first phase of Brazilian modernism. See the historical context in which it was inserted. Find out who their main authors and works were.

Understand what the 1922 Modern Art Week was all about. Find out which artists participated, what happened each day and why this event was so important.

Click here and see what are the main characteristics of the European vanguards. Find out how they came about and what purpose they had.