Baroque in Brazil it took place between 1601 and 1768, and was influenced by the measures of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, which took place in Europe. Its main features are the fusionism, the cult of contrast, O cultism it's the conceptualism. Thus, the main literary works of this style in Brazil are Prosopopoeia, by Bento Teixeira; the sermons, by Father António Vieira; in addition to the poetry of Gregório de Matos. In art, it is possible to point out the works of the famous sculptor Aleijadinho, the painter Mestre Ataíde and the conductor Lobo de Mesquita.

In Europe, baroque emerged at the end of the 16th century and lasted until the 18th century. Although this style is from italian origin, the main European authors are the writers Spanish Luis de Góngora and Francisco de Quevedo, from which the terms “gongorismo” (cultism) and “quevedismo” (conceptism) come from. Furthermore, it is also necessary to highlight the authors portuguese Francisco Rodrigues Lobo, Jerónimo Baía, António José da Silva, Soror Mariana Alcoforado, among others.

Read too: Classicism – European cultural movement prior to the Baroque

Historical context of baroque in Brazil

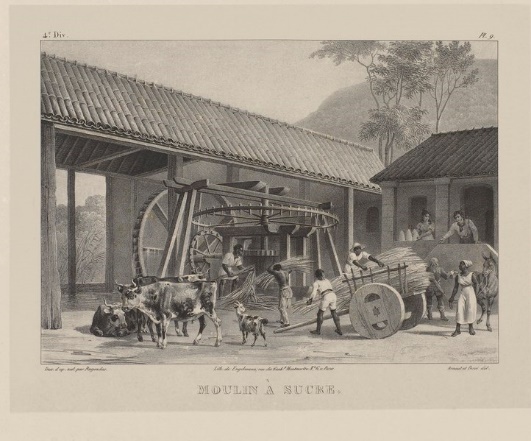

At the Brazil Colony, at the XVII century, the baroque aesthetic started to influence artists in Brazilian territory. In this period, Salvador and Recife were the main urban centers, as the country's economy was based on the exploitation of sugar cane, concentrated in the Northeast. Salvador was the capital of Brazil, the center of power, and the two main writers of Brazilian baroque lived there.

THE slavery of indigenous natives and African blacks, started in the previous century, was ongoing in the country. The work in the production of sugar cane was, therefore, carried out by slaves. There was still no idea of Brazil as a nation, the country's identity was under construction. The main cultural influence was Portuguese. In this way, the Christian religiosity dictated behavior of the people of the time, commanded by the Catholic Church.

At Europe, in the previous century, the Protestant Reformation provoked the reaction of the Catholic Church in what became known as Counter-Reform, creating measures to combat Protestantism, including the creation of Company of Jesus. The Jesuits, responsible for the catechization of indians, arrived in Brazil in the 16th century and remained in the country, where they exerted great political influence, until the 18th century, when they were expelled. the baroque author Father António Vieira (1608-1697) was one of the most important.

Baroque Characteristics

![The inspiration of Saint Matthew (1602), by the Baroque and Italian painter Caravaggio (1571-1610). [1]](/f/81364da30b8ff14a6060d66d6a458fd3.jpg)

Baroque in Brazil officially lasted from 1601 to 1768 and presented the following characteristics:

fusionism: combination of medieval and renaissance views.

contrast cult: opposition of ideas.

Antithesis and paradox: opposition figures.

Pessimism: negative attitude towards materiality.

feism: obsession with unpleasant images.

refining: excessive ornamentation of language.

Hyperbole: overkill.

Synesthesia: sensory appeal.

Cultism or gongorism: play on words (synonyms, antonyms, homonyms, puns, figures of speech, hyperbatics).

Conception or quevedism: game of ideas (comparisons and ingenious argumentation).

Morbidity.

feeling of fault.

carpe diem: enjoy the moment.

Use of the new measure: decasyllable verses.

Main themes:

human frailty;

time fleeting;

criticism of vanity;

contradictions of love.

Read too: Arcadianism in Brazil – a literary school whose main characteristic was bucolicism

Baroque works in Brazil

Prose

The bookthe sermons (1679), by Fr. António Vieira, is the main work of Brazilian and Portuguese baroque prose, as this author is part of the literature of both nations. They are conceptist texts, that is, with an ingenious argument in defense of an idea. To defend his point of view, Vieira used comparisons, antitheses and paradoxes. In the Baroque style, contrasting and contradictory, the priest combined faith with reason, since the content of His texts were religious, but also argumentative, that is, his Christian faith was defended through the reason.

Thus, the famous “Sermão de Santo António” — “Preached in S. Luís do Maranhão, three days before he secretly embarked for the Kingdom” —, among other things, criticism of bad preachers from metaphors (implicit comparisons), such as "the salt of the earth", where the "salt" is the preacher and the "earth" is the hearer of the preaching:

“You, says Christ our Lord, speaking with preachers, art the salt of the earth: and he calls them salt of the earth, because he wants them to do on earth what salt does. the salt effect is prevent corruption; but when the earth is as corrupt as ours is, there are so many in it who have salt craft, what will be, or what may be the cause of this corruption? or is it because the salt does not salt, or because the earth does not allow itself to be salted.”

Already in “Sermão de Santo António” — “Preached in Rome, at the Igreja dos Portugueses, and on the occasion when the Marquês das Minas, Ambassador Extraordinary of the Prince of Our Lord, made the Embassy of Obedience to the Holiness of Clement X” —, it is possible to see, as a mark of baroque, the paradox, when Vieira says that Santo António is “an Italian Portuguese” and “a Portuguese Italian”. Then he explains the contradiction: “From Lisbon [Portugal], because he gave birth to you; from Padua [Italy], because he gave her the grave”, where one can also see the antithesis in the opposition between “birth” and “burial”.

Next, the priest uses the metaphor "light of the world" to indicate that the saint led to christian faith for the world, because, as a good Portuguese, he did not stay in the land where he was born, as the Portuguese are famous for their achievements during the Great Navigations. So the priest honors both Church and nation Portuguese. It is also possible to perceive the paradox when Vieira says that the saint left Portugal to be great, and then says that he was great and, therefore, left:

“And if Antonio was light of the world, how could I not leave the motherland? This was the second move. He left the world as a light, and he came out as a Portuguese. Without leaving, nobody can be great: [...]. It went out to be big, and because it was big, it came out. [...]. That's what the great spirit of António did, and that's what he was obliged to do, because he was born Portuguese.”

Poetry

Although not considered to be of great value by critics, the book that inaugurated Brazilian baroque is the epic poem Prosopopoeia (1601), of Bento Teixeira (1561-1618). The biggest representative of baroque poetry in Brazil is Gregory of Matos (1636-1696), who did not publish books in his lifetime|1|, although the author was well known and talked about in his day — mainly because of his satirical poetry — due to the manuscripts shared among its readers at the time. In addition to this critical poetry, the poet also wrote sacred poetry (religious) and lyrical-philosophical poetry (of varied themes, including love ones).

As an example of your lyrical-philosophical poetry, let's read a sonnet classic, metric and with the use of the new measure (ten poetic syllables), in which the lyrical self makes the comparison of a woman by name Angelica common Angel is flower, very cultist style, with the play on words around the name Angelica, which comes from an angel and is also the name of a flower:

Angel in the name, Angelica in the face!

This is to be a flower, and an Angel together,

Being Angelica Flower, and Angel Florent,

In whom, if not in you, will he be uniform:

Whoever had seen such a flower, who hadn't cut it,

Green foot, from the flowering branch;

And whoever an Angel turns so bright,

That by his God he had not worshiped him?

If then as an Angel you are of my altars,

You were my custodian, and my guard,

Delivered me from diabolical misfortunes.

But I see, that because of beauty, and because of gallantry,

Since Angels never give regrets,

You are an Angel, who tempts me, and does not keep me.

As a copy of your sacred poetry, let's read the sonnet To Jesus Christ our Lord, which brings the theme of sin and of the fault. In this text, the lyrical self demonstrates that, however much he sins, he will be forgiven by God, as forgiveness is what makes this divinity a great being. Furthermore, it presents antitheses and paradoxes, as in the first verse, in which the lyrical self says that it sinned, but not sinned.

I sinned, Sir; but not because i have sin,

Of your high mercy I stripped me;

Because the more delinquent I have,

you have the to forgive more committed.

If it's enough to make you so angry sin,

To slow you down, a single moan remains:

that the same fault, who has offended you,

have you for the forgiveness flattered.

If a lost sheep is already charged,

Glory such is such a sudden pleasure

He gave you, as you affirm in sacred history,

I am, Lord, the stray sheep,

Collect it; and do not want, Divine Shepherd,

Lose your glory in your sheep.

Finally, as an example of your satirical poetry, let's read the sonnet the things of the world. In it, the lyrical self criticizes the human corruption, exemplified in the dishonesty of enrichment, hypocrisy, and false appearances. The sonnet is marked by the cultism (word play), as can be seen in the last stanza, with the pun involving the words "troop", "rag" and "gut":

In this world, the richest the most rapa:

Whoever is cleaner has more scale;

With his tongue, the nobleman the vile cuts off:

The biggest rogue always has a cape.

Show the rogue of the nobility the map:

Whoever has a hand to grasp, a quick climb;

Whoever speaks the least can, the more incredibly:

Anyone who has the money can be the Pope.

The low flower is inculcated with a tulip;

Cane in hand today, garlopa yesterday,

The more impartial is shown the one that sucks the most.

For the troop of the rag I empty the gut

And I don't say more, because Muse agrees

In apa, epa, ipa, opa, upa.

Authors of Baroque in Brazil

Bento Teixeira

There is little information about the author's life. So far, it is known that was born in Porto (Portugal), in 1561, about. He was the son of Jews converted to Catholicism, a new christian, therefore. He came to Brazil with his parents in 1567 and studied at a Jesuit college. He later became a professor in Pernambuco, but was accused by his wife of carrying out Jewish practices.

For that reason (or for her committing adultery), Bento Teixeira murdered the woman and took refuge in the Monastery of São Bento, in Olinda, where he wrote his only book. He was then arrested, sent to Lisbon, probably in 1595, and sentenced to life in prison in 1599. In the same year of his conviction, he was released on parole; but, without possessions and ill, he returned to prison to die in July 1600.

Gregory of Matos

Son of a rich family of Portuguese origin, the poet was born in Salvador, on December 20, 1636. In Brazil, he studied at a Jesuit college and later studied at the Coimbra University, in Portugal. Graduated in Law, he worked as a curator of orphans and criminal judge, but returned to Bahia to assume the positions of vicar general and chief treasurer of the Cathedral.

He was removed from office by unyieldedness and created many enmities due to criticisms he made in his poems, which earned him the nickname of mouth of hell. In 1694 he was deported to Angola. He later obtained permission to return to Brazil, but not Bahia, and died in Recife, in November 26, 1696 (or 1695).

Fr. António Vieira

Born in Lisbon (Portugal), on February 6, 1608. Son of a family without possessions, he came to Brazil in 1615. In savior, studied at a Jesuit college and entered the Company of Jesus in 1623. He pursued a diplomatic career in Lisbon, in 1641, and became friends with Dom João IV. But he also made enemies in Portugal by defend the jews.

Then he returned to Brazil. However, pursued by condemn Indian slavery, returned to Portugal in 1661, where he was condemned by Inquisition for heresy, but pardoned in 1669. From then onwards, he lived for a time in Rome, then again in Portugal, and finally returned to Brazil in 1681, where he died in Salvador that day. July 18, 1697.

See too: Parnassianism – poetic literary movement from the second half of the 20th century. XIX

Baroque in art

Baroque art in Brazil had its peak in XVIII century. Inspired by baroque European, Brazilian artists imprinted in their works typical elements of our growing culture (such as Nossa Senhora da Porciúncula, by Ataíde, with mulatto traits), characterizing the rococo — more subtle than Baroque, with softer colors, symmetrical strokes and less excess — a transition to neoclassical style. Originally, Baroque art is characterized by the exaggeration in ornamentation and colors, presence of twisted features and predominance of religious theme.

In Brazil, architecture favored the symmetry, as occurred in the sculptures of cripple, the most famous Brazilian Baroque artist. In his works, the duality it showed itself by combining symmetry (reason) with the religious theme (faith). Baroque-Rococo was strongly present in cities such as Mariana, Ouro Preto, Tiradentes (Minas Gerais) and Salvador (Bahia), in architecture of its churches, which, by the way, house the painting of artists of the period.

![Statue of the prophet Daniel, by Aleijadinho, in the Bom Jesus de Matosinhos Sanctuary, in Congonhas (MG). [2]](/f/430f39de11f14739d97806761fc6096b.jpg)

You main artists of baroque-rococo in Brazil are:

Mestre Valentim (1745-1813): sculptor.

Mestre Ataíde (1762-1830): painter.

Francisco Xavier de Brito (?-1751): sculptor.

Aleijadinho (Antônio Francisco Lisboa) (1738-1814): sculptor.

Lobo de Mesquita (1746-1805): musician.

Baroque in Europe

Although the baroque is from italian origin, the main European authors of this style are the Spanish Luis de Góngora (1561-1627) and Francisco de Quevedo (1580-1645). As for the Portuguese baroque (1580-1756), it is possible to point out the following authors:

Francisco Rodrigues Lobo (1580-1622): The prhyme (1601).

Jerónimo Bahia (1620-1688): poem To the boy God in a metaphor of candy.

António Barbosa Bacelar (1610-1663): sonnet to an absence.

António José da Silva (1705-1739), “the Jew”: Works of the pierced hand devil.

Gaspar Pires de Rebelo (1585-1642): The tragic misfortunes of the constant Florinda (1625).

Teresa Margarida da Silva and Orta (1711-1793): Adventures of Diophanes (1752).

D. Francisco Manuel de Melo (1608-1666): Metric works (1665).

Violating Heavenly Sor (1601-1693): Romance to Christ Crucified (1659).

Soror Mariana Alcoforado (1640-1723): Portuguese letters (1669).

Summary about baroque

- Historical context:

Brazil Colony;

-

Counter-Reform.

- Characteristics:

fusionism;

cult of contrast;

antithesis and paradox;

pessimism;

feism;

refining;

hyperbole;

synesthesia;

cultism or gongorism;

conceptism or quevedism;

morbidity;

guilt;

carp diem;

-

use of the new measure.

- Authors and works:

Prosopopoeia, by Bento Teixeira;

the sermons, by Fr. António Vieira;

-

sacred, lyrical-philosophical and satirical poetry by Gregório de Matos.

- Top artists:

Master Valentine;

Master Athaide;

Francisco Xavier de Brito;

Aleijadinho (Antonio Francisco Lisboa);

Wolf of Mosque.

solved exercises

Read the poetry below to answer questions 1 and 2.

TEXT

“The inconstancy of the world's goods”, by Gregório de Matos:

The sun rises, and it doesn't last more than a day,

After the Light follows the dark night,

In sad shadows beauty dies,

In continual sadness, joy.

However, if the sun ends, why did it rise?

If the Light is beautiful, why doesn't it last?

How is beauty thus transfigured?

How does the pen taste like that?

But in the Sun, and in the Light, the firmness is lacking,

In beauty, don't be constant,

And in joy feel sadness.

The world finally begins through ignorance,

And have any of the goods by nature

Firmness only in inconstancy.

MATOS, Gregory of. selected poems. São Paulo: FTD, 1998. for. 60.

Question 1 – (UFJF - adapted) In the poem read by Gregório de Matos, we can certify the following baroque characteristic:

A) cultism, due to the resources of far-fetched language.

B) medieval religiosity and paganism.

C) the resource of prosopopeia in the personification of the Sun and Light.

D) the conflict between the idealization of joy and the realization of sadness.

E) awareness of the fleetingness of time.

Resolution

Alternative E. In the sonnet, the “awareness of the fleetingness of time” is recurrent, as the lyrical self demonstrates its anguish in the face of the passage of time and the finitude of things.

Question 2 – (UFJF) Still in the poem by Gregório de Matos, the 2The stanza expresses, through rhetorical questions, the feeling of the lyrical self. Which option best expresses this feeling?

A) commotion

B) Resentment

C) Nonconformity

D) Vulnerability

And joy

Resolution

Alternative C. In the second stanza, it is possible to notice the nonconformity of the lyrical self due to his questions: “However, if the sun ends, why did it rise? / If the Light is beautiful, why doesn't it last? How is beauty thus transfigured? How does the pen taste like that?”. By asking such questions, he demonstrates that he does not conform to the finitude or inconstancy of things.

Question 3 – (Unimonts)

“See how the style of preaching in heaven says, with the style that Christ taught on earth. Both are sowing; the land sown with wheat, the sky strewn with stars. The preaching must be like one who sows, and not like one who tiles or tiles.” (Sermon of the Sixtieth, for. 127.)

With the fragment highlighted, Fr. António Vieira considers that

A) the preacher must use natural elements in the composition of the art of preaching.

B) the preacher must despise human actions to be successful in his preaching.

C) the preacher must use cultured vocabulary and sublime examples to compose his sermons.

D) the preacher must opt for clarity of words, abandoning verbal games and inversions.

Resolution

Alternative D. When saying that “The preaching must be like someone who sows, and not like someone who tiles or tiles”, Vieira opts for simplicity, for naturalness, that is, for the clarity of words.

Note

|1|The Academia Brasileira de Letras published the first edition of poems by Gregório de Matos (or attributed to him), in six volumes, between 1923 and 1933.

Image credits:

[1] PhotoFires / Shutterstock.com

[2] GTW / Shutterstock.com

by Warley Souza

Literature teacher

Source: Brazil School - https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/literatura/o-barroco-no-brasil.htm