THE War of the Rags, also known as Revolt of the Farrapos or RevolutionRagamuffin, was one of the provincial revolts that took place in Brazilian territory during the Governing Period. It gained notoriety for its longest duration (10 years), and, in addition, it was one of those that presented the greatest threat to the Brazilian territorial integrity.

Organized as a movement of the gaúcho elite, the Farrapos War ended after the government had negotiated peace between the gaúcho ranchers. The terms of surrender became known as the Poncho Verde Treaty.

Accessalso: Malês Revolt – the biggest slave revolt in Brazilian history

Causes

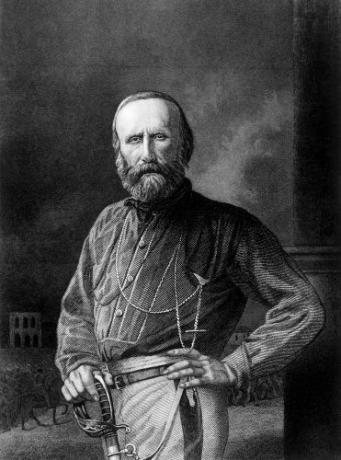

![In September 1836, the Farrapos declared the separation of Rio Grande do Sul from Brazil and the foundation of the Republic of Piratini. [1]](/f/c0f5118584960ba9f1e4b2a90f987f80.jpg)

The Farrapos War happened mainly because of the Gaucho ranchers' dissatisfaction with fiscal policy of the Brazilian government. In the 19th century, the province of Rio Grande do Sul had as its main product jerky (dried meat), which was sold as the main food for slaves in the Southeast and Northeast of Brazil.

The jerky was produced by the charqueadores, who bought the beef from the ranchers, the cattle raisers of Rio Grande do Sul. Their great dissatisfaction was related to the collection of taxes carried out by the government on the production of jerky in the region. Gaucho jerky received a heavy tax, while what was produced by Uruguayans and Argentines had a low tax.

This frame made the Gaucho productless competitive, since its price was higher. The main requirement of the ranchers was that foreign jerky be taxed to make competition between domestic and foreign products fairer. However, other reasons help to understand the beginning of this revolt:

Dissatisfaction with the taxation on cattle on the Brazil-Uruguay border;

Dissatisfaction with the creation of National guard;

Dissatisfaction with the government's refusal to assume the damages caused by a plague of ticks that attacked cattle in the region in 1834;

Dissatisfaction with the centralization of government and the lack of provincial autonomy;

Circulation of federalist and republican ideals in the region.

The sum of these factors led the gauchos to rebel against the central government on September 20, 1835. At first, the revolt was not separatist, but as the situation progressed, the breakaway gained strength.

Summary of events

As we have seen, the revolt carried out by the Farrapos began in September 20, 1835 and spread over a considerable part of the territory of Rio Grande do Sul. However, the announcement of the separation of the province only took place in September 1836, giving rise to the Rio Grande Republic, also known as RepublicinPiratini.

The Farrapos War was led by the rancher Bento Gonçalves, who was even the president of the Rio-Grandense Republic for some time. Other important names were the Italian GiuseppeGaribaldi and the one of the Brazilian military DavidCanabarro. Both were responsible for taking the war against the empire to the province of Santa Catarina, founding the Julian Republic, in July 1839.

The Julian Republic, however, was short-lived, as this region was retaken by the imperial government in November of the same year. The Farrapos War, despite its long duration and its extension to another province in southern Brazil, had, in general, low intensity combat. This is noticeable because, over 10 years, about three thousand people died (a cabin, for example, in five years, it resulted in 30 thousand deaths).

An important point is that there is no consensus among historians about whether the Farrapos really wanted to separate from Brazil or whether they just wanted to guarantee more autonomy for their province. Another point that deserves to be considered is that the fight of the Farrapos did not have the support of the entire Gaucho population (the city of Porto Alegre, for example, did not support them), because, as stated by Boris Faust:

[…] the revolt did not unite all sectors of the population of Rio Grande do Sul. It was prepared by border ranchers and some middle-class figures in the cities, gaining support mainly from these social sectors. The charqueadores that depended on Rio de Janeiro — Brazil's largest consumer center for jerked beef and leather — were on the side of the central government|1|.

The fighting focused on cavalry clashes, among which the victory of the Farrapos in the Battle of Seival. However, as the imperial reaction consolidated, the rags lost strength and left for the guerrilla war. Gaucho professor and journalist Juremir Machado da Silva says that the Farrapos assumed this strategy from 1842, when, according to him, the conflict was already settled in favor of the Empire Brazilian|2|.

To contain the revolt in the province of Rio Grande do Sul, the Brazilian government appointed Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, the Baron of Caxias (future Duque de Caxias). Caxias' action in front of 12,000 men was very efficient, as he managed to suffocate the rags with strategic military actions and, with diplomacy, lead them to negotiation.

Accessalso: How many coups have there been in Brazil since independence?

End of the Farrapos War

Peace was signed in Green Poncho Treaty, in which the Farrapos put an end to the revolt and, as defeated, accepted the terms proposed by the government.

The agreement between the Brazilian government and the Farrapos stipulated:

25% tax on foreign jerky;

Amnesty for those involved in the revolt;

Incorporation of the Farrapos military into the imperial army, maintaining their rank;

Provincials would have the right to choose their own provincial president (however, this was not fulfilled);

The slaves who fought on the side of the Farrapos would be freed (also an item not fulfilled).

Accessalso: November 15th – day of commemoration of the Proclamation of the Republic

Were the Farrapos abolitionists?

Historians now know that, alongside the Farrapos, there was a large participation of slaves and freed blacks. Such participation occurred due to the ability of many of them in important functions. However, many of these slaves also joined the ranchers' struggle for (false) promises of freedom that had been done to them.

The revolt carried out by the Farrapos it was not an abolitionist movement, since many of the ranchers and charqueadores had a large amount of slave workers, and therefore, for them, abolition was not economically viable. There were, yes, rags that defended the abolitionism, but the movement itself did not have on its agenda to promote the abolition of slavery, if they were victorious.

This issue is mainly elucidated by Juremir Machado da Silva, who claims that part of the Farrapos War was financed with the sale of slaves in Uruguay|3|. Another great controversy that divides historiography was the event of Battle of Porongos, on November 14, 1844.

The Battle of Porongos took place during the peace negotiations, and in it the group of black spearmen from the David Canabarro's troops were allegedly attacked by surprise by the imperial troops led by Moringue. However, some historians point to evidence that this attack was agreed between the Farrapos leaders and the government.

This attack, according to this interpretation, was the way to put an end to a controversy that hindered negotiations, since the imperial government refused to grant the freedom for runaway slaves who had joined the revolt, as this would be a precedent that could encourage slave escapes and revolts in other parts of the country. Brazil. The “surprise attack” had the objective of liquidating blacks and was, therefore, the way found to deal with this issue.

Grades

|1| FAUSTO, Boris. history of Brazil. São Paulo: Edusp, 2013. p.145.

|2| Juremir: “many commemorate the Revolution without knowing the history”. To access, click on here.

|3| Same as note 2.

Image credit

[1] commons

By Daniel Neves

History teacher

Source: Brazil School - https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/historiab/revolucao-farroupilha.htm