Tarsila do Amaral he figures among the best known and acclaimed names in national painting, being an icon of the brazilian modernism. Integrating several typical elements of the Brazilian culture, the artist was able to produce her own cultural identity, which assimilated the trends of modern European art, while giving them national colours.

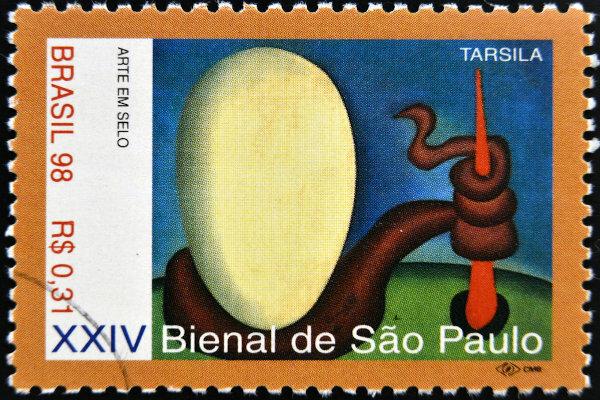

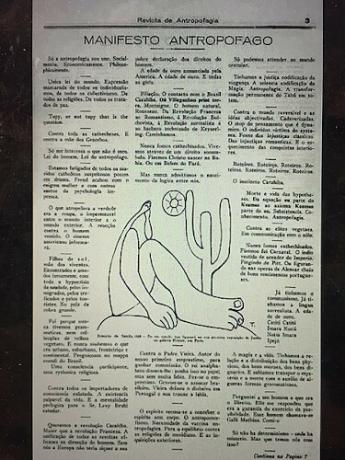

Beyond the modernist period, her most famous work, the abaporu, symbol of the 1928 Anthropophagous Manifesto, is also the most valuable painting in the history of Brazilian art. Furthermore, Tarsila do Amaral is one of the great representatives of Latin American art, with exhibitions dedicated to her circulating in major museums around the world.

Biography

Tarsila do Amaral was born on September 1, 1886, on the São Bernardo farm, in the municipality of Capivari (SP). In wealthy family, heiress of large rural properties in the interior of São Paulo, she grew up, together with seven siblings, listening to her mother play the piano and her father to recite poems in French, a language she learned since childhood. She was sent to the capital to study at Colegio Sion and then to Barcelona to complete her studies. In Spain, she painted her first painting,

Sacred heart of Jesus.Upon her return, she married the doctor André Teixeira Pinto, to whom she was engaged. The husband was bothered by his artistic craft, he imposed a demure and domestic behavior on Tarsila. After the birth of the couple's only daughter, Dulce, Tarsila then decided to separation. Thanks to the enormous influence of her family – who have always supported her career in the arts – she managed, in 1925, to annulment of your marriage (since divorce was not then allowed by law in Brazil).

In 1918, she began to have painting lessons in Pedro Alexandrino's studio, where he met the painter Anita Malfatti. In 1920, she left for Paris, where she remained until June 1922, studying at the Académie Julien and taking lessons with the painter Emile Renard. Was from letters sent by Malfatti that Tarsila became aware of the Modern Art Week, which took place in February 1922.

Back to São Paulo, Malfatti introduced Tarsila to modernist artists, and the “group of five”: Anita Malfatti, Oswald de Andrade, mario de andrade, Menotti del Picchia and Tarsila do Amaral. During this period, Tarsila and Oswald began a romantic relationship, making an official marriage a few years later. It was at this point that Tarsila started to produce modern art.

At the end of 1922, Tarsila returned to Paris, this time to study with cubist masters Albert Gleizes and Fernand Léger. The French-Swiss poet Blaise Cendrars introduced Tarsila and Oswald to the entire Parisian intelligentsia, including great names such as Picasso, the couple Delaunay and the musicians Stravinsky and Erik Satie. During this new stay in France, Tarsila became friends with other Brazilian artists who were there, such as Villa-Lobos and Di Cavalcanti, and also with patrons Paulo Prado and Olivia Guedes Penteado.

In 1925, Oswald released his book of poetry entitled Brazilwood, with illustrations by Tarsila. Oscillating between the great seasons in Europe and trips around Brazil in search of capturing the national colors for their canvases, premiered in 1926 with a solo exhibition in Paris, receiving very favorable reviews.

The big 1929 crisis, however, had inauspicious consequences for Tarsila. His family of farmers, who provided the necessary resources for so many trips to France, was affected by the coffee crisis and forced to sell the properties. Tarsila lost almost all her fortune and beyond that, separated from Oswald, then in love with student Patrícia Galvão, Pagu. Tarsila got a job at the São Paulo State Pinacoteca, a situation that also did not last long, as she was fired with the arrival of Getulio Vargas to power in 1930.

Unemployed and penniless, she sold some paintings and traveled, in 1931, to the Soviet Union, alongside her new husband, the psychiatrist Osório César. During this trip, Tarsila developed a new political conception, more aimed at social questions. Afterwards, she left for Paris, where she actually lived the working experience, working as a wall painter in buildings.

Tarsila divorced yet again, marrying writer Luiz Martins, twenty years her junior. The marriage lasted until the 1960s or so. In 1965, due to severe back pain, the painter underwent a surgical procedure, but due to a medical error, she was unable to walk. The following year, her daughter died of diabetes, which deeply shook Tarsila. Plunged into sadness and depression, Tarsila found the spiritism a relief – she became friends with Chico Xavier and began to donate, to a charity that he managed, everything she raised from the sale of her work.

Tarsila do Amaral died in São Paulo on January 17, 1973.

Read too: Modernism in Brazil – characteristics, phases, works

Tarsila and modernism

Although she did not actively participate in the 1922 Modern Art Week, Tarsila became the great name in the plastic arts of national modernism. It was only from her encounter with modernist artists that Tarsila actually developed the style for which she became known.

His travels through Brazil, especially through the interior of São Paulo and Minas Gerais, in 1923, gave him inspiration for his first influence compositions cubist, in stylized geometric shapes, making use of the colors considered “hillbilly” by their previous masters, linked to academic painting.

In the following excerpt, Tarsila reveals her intentions and her commitment to the search for a truly Brazilian art, modernist enterprise par excellence:

“I feel more and more Brazilian: I want to be the painter of my land. How I am grateful to have spent my entire childhood on the farm. The reminiscences of that time are becoming precious to me. In art, I want to be the caipirinha [from the farm] of São Bernardo, playing with wild dolls, like in the last painting I'm painting.”

(Letter from Tarsila do Amaral to the family, during her stay in Paris, in 1924)

Tarsila do Amaral's work is divided into three main phases: the first, called brazilwood; the second, anthropophagic, and the third, of imprint Social.

redwood phase

It is related to works produced between 1924 and 1928, based on trips to Rio de Janeiro, during Carnival, and to the historic cities of Minas Gerais. It is the application of such "Ribbon colors", rejected by the academic masters of paintings, and Tarsila's great intention in represent rural and urban Brazil in your pictures. The works from this phase expose the influence of Cubism and themes that are above all brazilian landscapes, such as Favela Hill (1924) and Sao Paulo (1924).

Anthropophagic phase

It began in 1928, from the iconic work abaporu – whose name is the combination of the words “aba” and “poru”, meaning “man who eats” in Tupi-Guarani. Painted as a birthday present to her then-husband, Oswald de Andrade, it became much more than that: it was the main inspiration for the writing of the Anthropophagous Manifesto and for the beginning of an artistic movement that had exponents in different segments of national art.

The central idea of the anthropophagous project was devour the influences of European culture, as they did not apply to Brazilian conditions, and from swallowing, modify what was devoured, producing genuinely national art.

Tarsila's anthropophagic painting mixes the modern learning of cubism with a universe of mystical and dreamlike density, quite rooted in Brazilian culture, making use of Vivid colors, such as red, purple, green and yellow. They are part of this phase, in addition to the abaporu (1928), the works the black (1923), which anticipated this phase, The Egg [Urutu] (1928), The moon (1928), Forest (1929), Sunset (1929), among others.

social phase

After her time in the Soviet Union and having worked as a construction wall painter in France, Tarsila began to reflect on her thematic works related to the proletariat, à social inequality, at oppressions suffered by the workers, to the problems of industrial capitalism.

The board the workers (1933) inaugurates this new pictorial phase, characterized by the use of more sober and grayer colors, a reflection of the hopelessness of those who, although working tirelessly, did not have access to basic goods such as health and education. The paintings are also considered a great icon of this phase. Second class (1933) and seamstresses (1936).

Read too:Cubism – the artistic avant-garde that influenced Tarsila

Main works

- the black (1923)

- the cuca (1924)

- Favela Hill (1924)

- Sao Paulo (1924)

- the papaya tree (1925)

- Self-portrait (Manteau Rouge) (1925)

- Manaca (1927)

- abaporu (1928)

- The egg (Urutu) (1928)

- Distance (1928)

- The moon (1928)

- Sleep (1928)

- Anthropophagy (1929)

- Sunset (1929)

- Forest (1929)

- Postcard (1929)

- Workers (1933)

- Second class (1933)

by Luiza Brandino

Literature teacher

Source: Brazil School - https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/biografia/tarsila-amaral.htm