During the first decades after the discovery of gold in the region of Minas Gerais, the colony of Portugal in America came under closer inspection by the employees of the Portuguese Crown. The exploration of gold, its commercialization and circulation among the inhabitants of the towns of the Minas region, without strict supervision, did not please the Portuguese metropolis. The creation of taxes and the intensification of their collections also did not please the inhabitants of the region. It was in this context of social tension that the Vila Rica Revolt, also known as Filipe dos Santos Revolt.

The situation was so tense in Minas that the region was described as follows:

“(...) the earth seems to evaporate turmoil; the water exalts riots; gold exchanges insults; the air pours freedom; the clouds spew insolence; the stars influence disorder; the climate is a tomb of peace and a cradle of rebellion; nature walks restless with itself, and mutinous inside, it's like hell”. [1]

In 1719, the Portuguese Crown began to intensify the collection of the fifth through the Foundry Houses. The fifth consisted of the delivery to the Metropolis of a fifth part (20%) of the gold extracted in the mines. In the Foundry Houses, the gold was smelted in bars, which facilitated the control over its circulation, guaranteed the efficiency of collection and avoided smuggling, usually carried out with the gold powder.

These measures of greater control over inspection displeased a good part of the population of Vila Rica, both the higher strata of society and the lower strata. With this dissatisfaction, in July 1720, the seditious began the Vila Rica Revolt. Armed groups formed by slaves and free men descended from the surrounding hills towards the city center, where they invaded houses to increase support for the struggle. The seditious also invaded the village Ombudsman's house, destroying official papers, in front of the revolting crowd. A few days later, Vila Rica was in the hands of the rebels.

Among other participants in the revolt were military, religious, doctors, chamberlains and merchants, as well as blacks and/or Indian archers. Among them was Filipe dos Santos, a drover of Portuguese origin, who earned his living working in the exchange of goods provided. by the internal trade that developed in that colonial period, fueled by the wealth of gold and the incipient urbanization of the Minas region.

Their objective was to extinguish the Foundry Houses, to force the withdrawal of D. Pedro de Almeida, Conde de Assumar, from the position of governor of the captaincy of Minas, in addition to accusing several other Crown officials at the site of corruption. As the Count was not in Vila Rica, but in Vila do Carmo, it was there that the rebels went to see their demands met.

Conde de Assumar received the rebels and began negotiations, stating that he would respond to their demands. Such a posture was nothing more than a way to buy time to gather military forces capable of confronting the groups that had risen. On July 17, 1720, the Count of Assumar decreed the arrest of the leaders of the Revolt, after managing to gather around 1500 armed men who went to Vila Rica. Within two days, the rebellion was suppressed and the leaders arrested.

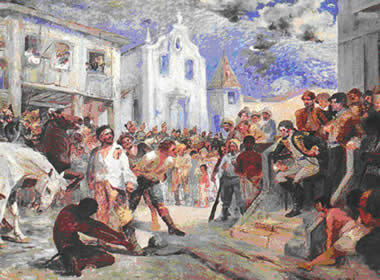

Canvas by Antônio Parreiras (1860-1937) portraying the trial of Filipe dos Santos

On July 19 and 20, Filipe dos Santos was tried and sentenced to death for his participation in the Revolt. He was dragged through the city streets and dismembered. The goal was for his death to serve as an example to those who dared to stand up to the officials and the Crown Portuguese, mainly with regard to the collection of taxes on the exploitation of the mineral wealth of the Cologne.

The consequences of the Vila Rica Revolt were the separation of the mine region from the captaincy of São Paulo and increased inspection of gold extraction, thus ensuring the shipment of gold to the Metropolis.

[1]Historical and political discourse on the uprising that took place in Minas in the year 1720. Belo Horizonte: João Pinheiro Foundation, 1994. Critical study by Laura de Mello e Souza. P. 97. Apud. MATHIAS, Carlos Leonardo Kelmer. Games of interests and action strategies in the context of the Vila Rica mining revolt, c. 1709 – c. 1736. Masters dissertation. Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ, 2005.

By Tales Pinto

Master in History

Source: Brazil School - https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/historiab/revolta-vila-rica.htm