Artur Costa e Silva was the second president of Brazil during the period of Military dictatorship, ruling the country from 1967 to 1969. Costa e Silva's government marks the beginning of the development measures that led to the “economic miracle”, besides being marked for having started the “years of lead”, period of greatest repression of the Military Dictatorship.

Costa e Silva government

Artur Costa e Silva assumed the presidency on March 15, 1967, after winning the indirect election that was contested in 1966 and for which he was the only candidate. Costa e Silva's victory to assume the presidency was the result of a campaign within the Army itself to increase the apparatus of repression of the Dictatorship.

The government of his predecessor, Castello Branco, is wrongly seen as a time of little repression, but in fact recent studies show that it was a transitional period in which the repressive apparatus was established in a way that would not cause a rupture between the regime and society. civil.

Also access: Government of Humberto Castello Branco

Even so, Castello Branco was pressured by the Armed Forces to leave power, and the transition was carried out with the nomination of Costa e Silva. Paradoxically, the election of Costa e Silva was seen by certain elements of society as a hope of liberalization of the regime, and the marshal himself stated that he would prepare an “authentically Wow".1

Despite the speech, the Costa e Silva government consolidated the transition to the most repressive period of the dictatorship, expanding the repressive apparatus of the movement, pursuing student and workers movements and concluding this process with the decree of Institutional Act No. 5 at the end of the year 1968.

Economic policy

The Costa e Silva government broke, in part, with the economic policy of the previous government. The predecessor Castello Branco had an economic policy characterized by a squeeze, with the freezing of wages and government spending and reduced credit to reduce consumption and, consequently, inflation. Castello Branco took tough measures, mainly on the worker's salary, which made the salary increase always smaller in relation to the previous year's inflation.

From the Costa e Silva government onwards, a developmental economic policy, in other words, that it would promote a rapid economic development of the country, similar to those applied in the 1950s, but with another ideological inspiration. In addition, Costa e Silva's economic policy aimed to stimulate consumption and public investment.

This policy inaugurated by Costa e Silva in 1967 gave birth to the period known as “economic miracle”, which ran from 1968 to 1973. This period was characterized by a rapid heating of the economy and very high economic growth rates. Regarding the “economic miracle”, historians Lilia Schwarcz and Heloísa Starling make the following consideration:

The miracle had an earthly explanation. It mixed, with the repression of opponents, the censorship of newspapers and other media, in order to prevent the airing of criticism of the economic policy, and added the ingredients of the agenda of this policy: government subsidy and export diversification, denationalization of the economy with the growing entry of foreign companies into the market, control of price adjustments and centralized fixing of wage adjustments.2

The results for the economy during the “economic miracle” were expressive: in 1968, the GDP grew 11.2%, and in 1969 the growth was 10%3, but the price to be paid was very high. During this period, one tolong process of income concentration, intensifying the inequality of society and the government indebtedness, which began to soar.

opposition grows

From 1967 onwards, opposition to the regime grew on several fronts and organized itself. The result was an imminent confrontation between the government and these opposition groups, which led to the hardening of the regime, consolidating a process that had been underway since Castello Branco took office, in 1964.

At the political field, important cadres who had supported the coup began to break with the regime. Among them stand out Ademar de Barros and Carloslacerda, two names in Brazilian conservatism who openly supported the 1964 coup. Carlos Lacerda even went so far as to say: “I had a duty to mobilize the people to correct this error in which […] I participated.4

The action taken by Carlos Lacerda was to organize the Wide Front, which was active during the years of Costa e Silva's government. The Frente Amplio was a political movement that basically defended Brazil's return to democracy, in addition to proposing the continuation of an economic policy that would promote the country's development.

The Broad Front had the support of juscelinoKubitschek and JoãoGoulart – both harshly criticized by Lacerda during his administrations. From the perspective of the Frente Amplio, new presidential elections should be held, with the fight against the threat that surrounded the country – the dictatorship. Banned from acting after 1968, the Frente Amplio represented an effort by Carlos Lacerda to create a bridge of dialogue with the regime with the aim of redemocratizing the country.

Do not stop now... There's more after the advertising ;)

Read too: JK governmentandJango government

O student movement during the 1967/1968 cycle, it played an extremely important role in the struggle against the regime. The protests got stronger from March 1968, when student Edson Luís was killed by the police during a small protest in the city of Rio de Janeiro. This fact caused a commotion, and his wake was attended by thousands of people.

Then began a series of gigantic protests, which lasted until mid-July 1968. The protests of the following months were harshly repressed by the police and the clashes with students were quite violent. A defining moment took place on June 26, in what became known as Hundred Thousand March, which had wide participation of students, artists and intellectuals.

The government's response was repression: in July protests were banned, and in August there was an invasion of the University of Brasília (UnB). The hardening of this repression made several student groups join the armed struggle as a form of resistance to the regime.

Finally, another opposition movement that acted consistently during a certain period of the government of Artur Costa e Silva was the labor movement. The wage freeze implemented from 1964 on had a strong impact on workers' income. The continuity of this situation led to two important strikes in the country: one in Minas Gerais and another in São Paulo.

The strike in Minas began in April 1968, in a steel plant located in Contagem (the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte). The movement took the government by surprise and mobilized around 16,000 workers. The government was forced to negotiate and agreed to readjust wages by 10%, but there was still repression, with the arrest of workers and occupation of the city of Contagem.

Three months later, another strike broke out in Osasco, in the state of São Paulo, and started with 10,000 workers crossing their arms. This time, the government did not negotiate and the repression was very harsh: the city was occupied, with hundreds of workers imprisoned, and the union leaders had to disappear underground. Government repression put the labor movement to sleep for a decade.

Institutional Act No. 5

The regime's response to the strengthening of opposition movements was to institutionalization of repression. Institutional Act No. 5 (better known as AI-5) was enacted on December 13, 1968. The trigger for his decree was the action of lawmakers in opposing the punishment of deputy Márcio Moreira Alves.

In September 1968, this deputy had criticized the regime, calling the army a “valcouto of torturers” (equivalent to asylum, refuge, shelter for torturers). The government demanded that the politician be prosecuted, but the government's action was defeated in the Chamber of Deputies by 216 votes to 141 votes5. With the threat that the regime would lose control over political cadres, the answer was to toughen up.

The meeting that defined the AI-5 decree was known as “Black Mass”, and the Institutional Act was read on the radio throughout the country by the Minister of Justice, Gama e Silva. Lilia Schwarcz and Heloísa Starling define this Institutional Act as follows: “The AI-5 was a tool for intimidation by fear, it had no term and would be used by the dictatorship against the opposition and the disagreement".6

End of the Costa e Silva government

Artur Costa e Silva's government lasted until March 1969, when the military president suffered a stroke that permanently removed him from the presidency. As a result of this episode, he died a few months later. Until October 1969, Brazil was governed by a Provisional Military Junta, which transferred power to emiliO Garrastazu medical.

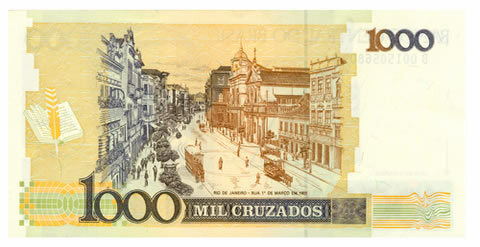

*Image credits:FGV / CPDOC

1NAPOLITANO, Marcos. 1964: history of the military regime. São Paulo: Context, 2016, p. 86.

2 SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz; STARLING, Heloisa Murgel. Brazil: a biography. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015, p. 452-453.

3 FAUSTO, Boris. history of Brazil. São Paulo: Edusp, 2013, p. 411.

4 NAPOLITANO, Marcos. 1964: 1964: history of the military regime. São Paulo: Context, 2016, p. 84.

5 Idem, p. 93

6 SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz; STARLING, Heloisa Murgel. Brazil: a biography. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015, p. 455.

By Daniel Neves

Graduated in History