Brazil only became a sovereign nation, in fact, with the Independence, declared in September 7, 1822 by the then Prince Regent Pedro de Alcantara, who became our first head of state under the title of D. Peter I. Since then, episodes of intense turmoil have not been lacking in our political scenario.

Since Independence, we have had various types of revolts, attempted coups and coups effectively applied. In this text we will deal with these last ones, the effective blows. If one coup d'etat is defined as a subversion of the institutional order, so we can say that, in the period discussed here (from 1822 to the present day), we had at least nineblows in Brazil. See what they were!

1) The “Night of Agony”: dissolution of the Constituent Assembly of 1823

A little over a year after Independence, Brazil experienced the first coup, given by Emperor D. Pedro I against the first Brazilian Constituent General Assembly. This Assembly was elected and installed on May 3, 1823 with the objective of preparing the first constitutional text for Brazil.

D. Pedro I watched, from the windows of the Imperial Palace, the movements of the Constituent Assembly.

The main reason for the dissolution was related to the internal political disputes of the constituents, which were divided between liberals (moderate and radical) and conservatives. One of the members of the Constituent Assembly, José Bonifácio de Andrade e Silva, was minister of D. Pedro I and began to make direct access between conservatives and the Emperor himself difficult. D. Pedro I then removed Bonifácio from the position. The latter, in turn, reacted violently against the government through newspaper articles.

Under pressure, the Emperor opted for the dissolution of the Assembly, which occurred in the morning of the day November 12, 1823, which became known as “the night of agony”. D. Pedro I, with military help, ordered a siege to be made to the building where the constituent deputies were meeting. Many of those present resisted the emperor's onslaught and ended up imprisoned and later exiled.

To complete the work of preparing the constitutional text, D. Pedro I organized a Council of State, composed of men of his entire confidence. This Council presented the final draft of the Constitution on December 11, 1823. In March 25, 1824, the emperor approved the Imperial Constitution without this being appreciated by an Assembly.

2) Coup of Majority (1840)

The second coup d'état we had was the Coup of Age, which took place on July 23, 1840. This coup happened in Governing Period, a mode of government formed after the Abdication of D. Peter I, in 1831. The heir to the throne, the future D. Pedro II, was just a child of six years of age and, therefore, had to reach the age of majority to be able to govern.

Just like today, the age of majority at that time was 18 years old. As long as the emperor was not of that age, the leadership of the country was entrusted to regents, who had the legal support of the Imperial Constitution of 1824 to exercise their function. This same Imperial Constitution also determined, in its article 121, that the emperor could only assume power at 18 years of age.

The advance of the coronation of D. Pedro II is also configured as a coup d'état.

The Regency Period, however, was marked by intense political complications. The dispute between liberals and conservatives was at its height. In this tense climate, a group of deputies and senators, led by men like JosephMartinianinAlencar and NetherlandsCavalcanti, they organized the so-called “Major Club” with the aim of advancing the inauguration of Pedro II, then 15 years old.

Members of this group presented proposals to reform the Constitution and other projects aimed at enthroning the young emperor. However, all were rejected. It remained for them to appeal for an articulation with the emperor himself, who was persuaded by his tutor to want to ascend to the throne soon. With the adhesion of Pedro II himself to the majority group, the then regent BernardPereirainVasconcelos ended up giving in to pressure from the majorists, even though their proposals were unconstitutional. Dom Pedro II became emperor on July 23, 1840.

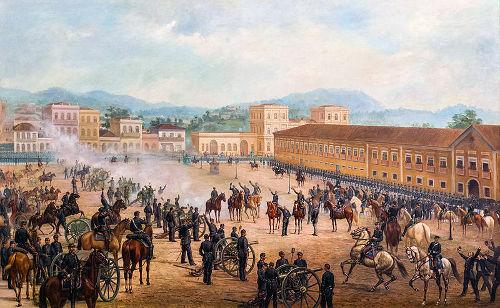

3) Proclamation of the Republic (1889)

what we commonly know as "Proclamation of the Republic", occurred on the day November 15, 1889, was, in fact, a military coup that ended the monarchic regime in Brazil. The republican movement in Brazil dates back to colonial times, but it became really intense at the time of the Second Reign. Some prominent leaders of this movement were linked to the Brazilian army, as was the case of Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Constant.

The Proclamation of the Republic was a military coup that deposed Emperor Dom Pedro II.

Republicans were intimately influenced by the positivism of augustComte, which implied the idea of a strong State, antimonarchic and dissociated from the Church. For the coup against the monarchy to be successful, the republicans needed the support of the main military authority of the time: the marshal Deodoro da Fonseca. It turns out that Deodoro was a royalist and a personal friend of the emperor.

In order to convince Deodoro to "proclaim the Republic", the conspirators, such as Benjamin Constant, used the argument of damages that the decisions of the then minister of Pedro II, Viscount of Ouro Preto, entailed the Army – which was in poor condition at the time. Furthermore, the marshal was told that, in place of Ouro Preto, a former personal enemy of Deodoro would be named, Gaspar da Silveira Martins. Faced with this situation, Deodoro gathered a few hundred soldiers and marched on the city of Rio de Janeiro with the aim of overthrowing the Ouro Preto ministry.

This gesture, on November 15, 1889, put an end to the monarchy in Brazil.

4) Coup of November 3, 1891

Given the coup of November 15, Deodoro, the monarchist who overthrew the monarchy, ended up being the interim head of the republic until it had a Constitution. The republican constitutional text was approved in February 14, 1891. Deodoro da Fonseca was indirectly elected President of the Republic. Second, there was another marshal, Floriano Peixoto, like vice.

In his first year as president-elect, Deodoro da Fonseca, to solve the problem of the pressure that the opposition was exerting on his government, dissolved, via decree, the CongressNational in November 3, 1891. Then, to complete the coup, he instituted, with another decree, State of siege in Brazil, which authorized the army to surround the Chamber and Senate and arrest opposition politicians.

5) The curious case of Floriano Peixoto

Twenty days after the November 3 coup, Deodoro da Fonseca resigned as president, in response to the reaction of the Brazilian navy, which threatened to bomb the city of Rio de Janeiro if the president remained in office. This navy reaction became known as First Armada Revolt.

In place of Deodoro, he took the vice, Floriano Peixoto. As there was not yet a year of Deodoro's mandate, what the Constitution provided for was the calling of new presidential elections. However, Marshal Floriano did not call new elections with the justification that the Constitution of 1891 had provisions that determined the call of new elections only if the president had been directly elected by the people, which did not happen in the case of Deodoro da Phonseca.

This curious constitutional impasse kept Floriano in power, who had to face the Second Armada Revolt and a series of other uprisings against his government with "an iron fist". Even having rehabilitated the National Congress, Floriano assumed an undeniable dictatorial profile in the time he was in power, which makes the discussion about the coup he would have done or not enough complex.

6) 1930 Revolution

THE 1930 revolution it was a civil-military coup led by leaders from the states of Paraíba, Rio Grande do Sul and Minas Gerais, who together fought against the rest of the country.

The trigger for the explosion of the 1930 Revolution was the presidential elections of that year. As usual in the years of old republic, the election result was rigged and the candidate of the situation, Julius Prestes, appointed as successor to the then president Washington Luis, the new president was elected.

The Revolution of 1930, which toppled President Washington Luis, was also a coup.

The opposition candidate (called Liberal Alliance), defeated, was the gaucho Getúlio Dorneles Vargas. Contrary to what had happened before, the opposition did not accept the fraudulent result and went for physical confrontation. The event that caused the greatest revolt and exacerbated the conflicts was the death of the governor of Paraíba, João Pessoa. After this event, members of the state police in Minas, Rio Grande do Sul and Paraíba, as well as some sectors of the army, joined the revolutionaries.

The government, as historian José Murilo de Carvalho says:

“[...] had military superiority over the rebels, but the high command lacked the will to defend legality. The military leaders knew that the sympathies of the young officers and the population were with the rebels. A junta made up of two generals and an admiral decided to depose the President of the Republic and hand the government over to the head of the insurgent movement, the defeated candidate of the Liberal Alliance. Without major battles, the First Republic fell, at 41 years of age.” (Oak, José Murilo de. Citizenship in Brazil: the long way. Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Civilization, 2015. P. 100).

Thus ended the “First Republic”, or “Old Republic”, by means of yet another coup d'état.

7) "Estado Novo" (1937)

After being indirectly elected President of the Republic in 1934 (therefore 4 years after the Revolution that brought him to power), Vargas had to deal with other problems. The main one was the call Communist intent, led by young army officers associated with the National Liberating Action (communist body created by Luís Carlos Prestes). Intentona broke out in states such as Rio Grande do Norte, Rio de Janeiro and Pernambuco, but was soon taken over by government forces.

The problem is that, in the years that followed, the communism it's the tenentism associated with him, they were still considered by the top Army leadership and by civilian leaders close to Vargas as the main targets to be fought. In 1937, an alleged plan for a communist revolution to be carried out in Brazil was discovered, the so-called Cohen Plan. This plan would have been forged by the captain Olímpio Mourão Filho in order to provoke public opinion and justify a coup d'état and the formation of thenew state.

It is unclear whether this document was really a forged plan or just a report of Olímpio Mourão, but the fact is that the finding of its existence provoked opportunistic reactions by part of Army Staff. Vargas's minister of war, Eurico Gaspar Dutra, read the Cohen Plan to the radio audience on the program Voz do Brasil. This was enough for the approval of the National Congress on September 30, 1937, the state of war, which suspended constitutional rights.

In mid-October, the war ministry supported Vargas' project to pressure states that did not yet have their military forces subordinate to the federal government to do so. One of the last resistances to be overcome was that of Gaucho Military Brigade, led by wedge flowersIn October, Vargas already had the support of the army, the Integralists and many sectors of civil society, and no significant regional military resistance to oppose him.

On November 10, through a public statement, Vargas decreed the closing of the National Congress and canceled the presidential elections that would be held in January 1938. Through this coup, the Vargas dictatorship lasted until 1945.

8) Deposition of Getúlio Vargas in 1945

Virtually the same military that supported the 1937 coup removed Vargas as head of state in 1945. The context of the coup that deposed Vargas as president in October 29, 1945 it was the end of Second World War. As is well known, Vargas was from 1937 to 1945 a dictator in the mold of European fascism, having even approached Nazi Germany at the beginning of the Estado Novo.

In the middle of the second world conflict, Vargas broke with Germany and started to support the allied powers, such as the USA, England and the USSR, which won the war. Therefore, it would not be appropriate to continue a regime along the lines of the Estado Novo. Under pressure, Vargas then began a process of democratic opening, which enabled the creation of new political parties, such as the UDN (National Democratic Union), the PCB (Brazilian Communist Party), which returned to legality) and the PSD (Social Democratic Party), and perspective of new general elections.

Vargas, however, decided to lead this transition process with a view to obtaining political support from other bases in society and, thus, managing to remain in power in other ways. In this way, in a controversial way, Vargas approached the PCB and the urban workers bases, contradicting the liberal and military leaders. This approach to the PCB resulted in the "querism", a popular movement that wanted Vargas to remain in power and demanded the formation of a new National Constituent Assembly.

In the midst of these turbulent events, Vargas committed a gesture considered to be the “drop of water” for his deposition: he removed him from the Federal District's police chief. João Alberto Lins de Barros and put in his place his brother BenjaminVargas, known for being truculent. the general Gois Monteiro, who had helped make the 1930 Revolution, from the War Ministry, reacted to Vargas' gesture and mobilized troops in the Federal District.

Gaspar Dutra and other soldiers, seeking to avoid bloodshed, proposed to Vargas that he sign a document to resign from office. The Gaucho politician did so and was able to take refuge in his hometown, São Borja, without having to go into exile in another country.

9) March 31 to April 2, 1964

The debates around the 1964 coup are quite controversial, but the facts are as follows: João Goulart, in 1963 and 1964, presented a controversial posture by inciting low-ranking military personnel, such as sergeants, to insubordinate themselves against the hierarchy military. This was made explicit in his meeting with warrant officers and sergeants in the Automobile Club, on March 30, 1964, considered the last straw for the coup.

João Goulart had the government overthrown between March 31 and April 2, 1964.

In addition to supporting demands for reforms within the military structure, Goulart also had proposals for basic reforms in other sectors, such as the agrarian sector. These reforms had, in the eyes of their critics, a radical content that was very close to the communist political perspective. In addition, there were movements of guerrilla outbreaks in Brazil, such as the leaguesPeasants in Franciscojulian – popular leader who had visited Fidel Castro in 1961 – who put the military on alert.

In the midst of this ambience, the episode of the Automobile Club, mentioned above, was enough for the general to, in the early morning of March 31, Olímpio Mourão Filho mobilize its troops from Juiz de Fora against the government. At the same time, in Rio de Janeiro, Costa e Silva led another offensive, independent of that of Mourão.

Goulart, the day after these actions, had not yet manifested. On April 2, the National Congress, thinking that the president had gone into exile, declared the presidency vacant. The President of Congress, RanieriMazzili, he took over the post. The problem was that Goulart had not left the country, but it was too late. The decision of the Congress was taken and more than that: the decision of the generals was taken, given that they installed the Supreme Revolutionary Command and chose, through the Institutional Act No. 1, a new president for Congress.

The problem with understanding the 1964 coup is, therefore, in three points:

1. Could Goulart have given way to a communist/military coup (similar to the Communist Intentona of 1935) and, therefore, was there a reaction from the Brazilian generals?

2. Did Congress err in declaring the chair of the presidency vacant too soon?

3. Did the military err in instituting the Supreme Revolutionary Command, not respecting the National Congress, which had already placed Renieri Mazzili at the head of the country?

These issues are still exhaustingly debated by historians, politicians and journalists. However, as there was a break with the institutional order, the actions from March 31 to April 2, 1964 can indeed be classified as a coup.

By Me. Cláudio Fernandes

Source: Brazil School - https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/historia/quantos-golpes-estado-houve-no-brasil-desde-independencia.htm