THE Revolt of the whip it was a military agitation in the Brazilian Navy, which took place in Rio de Janeiro, from November 22 to 27, 1910.

The fight against physical punishment, low wages and terrible working conditions are the main causes of the revolt.

Historical context

At the time, it is worth noting that in the Brazilian Navy, sailors were mainly black slaves who had recently been freed. These were subjected to an arduous work routine in exchange for low wages.

Any dissatisfaction was punishable and discipline on the ships was maintained by the officers through physical punishment, of which “lashing” was the most common punishment.

Despite having been abolished in most of the world's armed forces, physical punishment was still a reality in Brazil.

The dissatisfaction of the sailors grew after the officers received salary increases, but not the sailors.

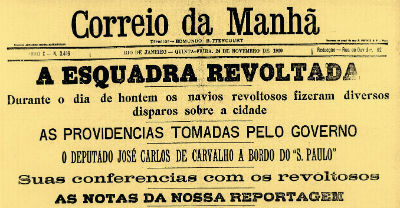

Front page of the newspaper Correio da Manhã, on November 24, 1910.

In addition, the new and modern battleships that the Brazilian government had ordered, the "Minas Gerais" and the "São Paulo", demanded an even larger number of men to be operated on, overloading the sailors. These two warships were the most powerful and modern in the Brazilian fleet.

Thus, with the increase in the salaries of officers and the creation of a new table of services that did not reach the lower ranks, some sailors began to plan a protest.

the uprising

In the early hours of November 22, 1910, the sailors of the Battleship "Minas Gerais" rebelled.

The trigger came after watching the punishment of the sailor Marcelino Rodrigues Menezes, whipped until he passed out with 250 lashes (the normal was 25) for assaulting an officer.

The uprising was led by the experienced João Cândido Felisberto, Black and illiterate sailor. The mutiny ended with the death of the ship's commander and two other officers, who refused to abandon the warship.

That same night, the Battleship "São Paulo" joined the mutiny. In the following days, other vessels joined the movement, such as the "Deodoro" and the "Bahia", large warships.

In turn, in Rio de Janeiro, the president Hermes da Fonseca he had just taken office and was facing his first crisis. Rebel ships bombed the city of Rio de Janeiro to demonstrate that they were not dissembling.

In a letter to the government, the rebels requested:

- the end of physical punishment;

- better food and work conditions;

- amnesty for everyone involved in the revolt.

Thus, on November 26, President Marshal Hermes da Fonseca accepted the demands of the mutineers, ending that episode of the revolt.

However, two days after handing over the weapons, a “state of siege” was decreed, initiating the purge and imprisonment of those sailors considered undisciplined.

End of Revolt

João Cândido, third from left to right, on the third day of the revolt.

The sailors were arrested on Ilha das Cobras, headquarters of the Naval Battalion. Feeling betrayed, the sailors mutinied on December 9, 1910.

The government's response was harsh and the prison was bombed and destroyed by the army, killing hundreds of marines and prisoners.

The mutineers, totaling 37 people, were taken to two solitary confinements, where they died of suffocation. Only João Cândido and another fighting companion survived.

As a result, in 1911, those who joined the movement had already been killed, imprisoned or expelled from military service. Many of those involved were sent to forced labor camps in the Amazon rubber plantations and in the construction of the Madeira-Mamoré railway.

As a result, the conflict left more than two hundred dead and wounded among the mutineers, of which about two thousand were expelled after the revolt. In the legalist portion, about a dozen people died, including officers and sailors.

As for the leader, João Cândido, after surviving imprisonment and being acquitted, he was considered unbalanced and interned in a hospice. For his audacity, the press at the time called him the Black Admiral.

He would be acquitted of conspiracy charges on December 1, 1912, but was expelled from the Navy.

He survived as a fisherman and seller until journalist Edmar Morel rescued his story from oblivion and released the book "The Chibata Revolt", in 1959.

Only on July 23, 2008, the Brazilian government understood that the causes of the revolt were legitimate and granted amnesty to the sailors involved.

Curiosities

- The Chibata Revolt was inspired by the mutiny of the sailors of the Russian Imperial Navy, carried out on the battleship Potemkin, in 1905.

- The music "The Master of the Seas", composed by João Bosco and Aldir Blanc, in 1975, was made in honor of the leader of the Chibata Revolt. The lyrics were censored by the military regime.

- Currently, there is a statue of João Cândido in Praça XV, in Rio de Janeiro, placed there in 2008.

read more:

First Republic

Petropolis Treaty