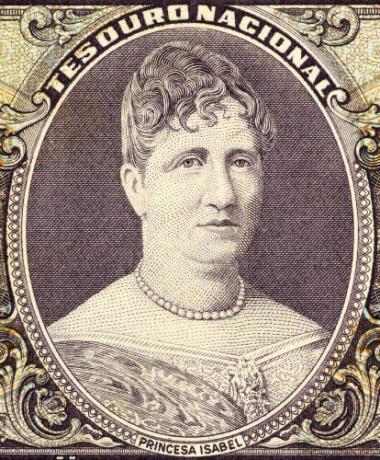

A abolition of slavery was one of the most remarkable events in the history of Brazil and determined the end the enslavement of blacks in Brazil. The abolition of slave labor took place through the Lei Áurea, approved on May 13, 1888 with the signature of the regent of Brazil, Princess Isabel. The abolition of slavery was the conclusion of a popular campaign that pressured the Empire to have the institution of slavery abolished in our country.

Also access:What is racism and how can it manifest itself?

Summary on the abolition of slavery

The abolition of slavery was a topic that crossed the political debate in Brazil during the 19th century.

In 1850, as a result of pressure from the British, the Eusébio de Queirós Law was approved in Brazil, a law that prohibited the slave trade.

Great names in Brazilian abolitionism were Luís Gama, André Rebouças and José do Patrocínio.

The Abolitionist Confederation was the largest abolitionist association in the country and organized actions for the cause in Brazil.

Some abolitionist laws approved during the course were the Free Womb Law and the Sexagenarian Law.

The abolitionist movements organized themselves in different ways, such as disseminating pamphlets, organizing conferences, etc.

Slaves also resisted, organizing escapes, revolting against their masters, etc.

The abolition took place on May 13, 1888, when the Lei Áurea was signed by Princess Isabel.

Historical context of the abolition of slavery

The abolition of slave labor was a subject debated in our country throughout the 19th century. This subject was already discussed by some personalities in the first years of our independence, like José Bonifácio, and dragged along the entire monarchical period. But the first issue that took on real importance in the political scenario of our country was the prohibition of the slave trade.

Trafficking existed in Brazil since the mid-16th century, however, in the 19th century, the British began to pressure, first, Portugal and then Brazil for the slave trade to be prohibited here. British pressure made Brazil assume commitments with the prohibition of slave trade, in the 1820s.

This commitment resulted in the Feijó Law of 1831, but even so, the slave trade continued, landing thousands of Africans every year in Brazil. In 1845, England, enraged by Brazil's permissive stance on the slave trade, enacted the Aberdeen Bill, a law that allowed British vessels to invade our territorial waters to seize slave ships.

The risk of a war between Brazil and England due to Bill Aberdeen led to the approval of a law, in 1850, known as the Eusébio de Queirós Law. This law decreed a definitive prohibition on the slave trade in Brazil, but allowed the Africans who arrived after the 1831 law to continue as slaves. With this law, the repression of the slave trade was effective and, from 1851 to 1856, “only” 6900 Africans arrived in Brazil|1|.

With the prohibition of trafficking, a transition process began, since, once the source that renewed the numbers of slaves in Brazil ended, it was natural that over time slavery in the country would be abolished, since there was no natural renewal of the slave population in the country. country. The slaveholders' intention was to make this transition as long as possible.

In the 1860s, pressure on the Empire to end slavery was enormous., because Russia had ended serfdom on its territory, and the United States had abolished slavery after the civil war. This made Brazil, Puerto Rico and Cuba the last slaveholding places on the American continent.

In this context, the abolitionist movement began to structure itself, but, politically, the agenda did not advance due to the war in paraguay. With the end of the conflict, in 1870, the abolitionist movements gained strength and the debate for the end of Slavery, in addition to becoming an important agenda in politics, has also become a relevant debate in society. Brazilian.

Also access: The trajectory of three important black abolitionists in Brazil

Abolitionist movement in Brazil

The abolition of slavery in Brazil was not the result of the benevolence of the Empire, as many believe. This achievement was the result of popular engagement against this institution, and popular pressure on the Empire was the factor that caused slavery to be abolished on May 13, 1888.

As the abolitionist movement gained strength, slaveholding groups articulated politically to stop the advance of abolitionism. The debate in the political field led to the approval of a law, in 1871, known as the Lei do Ventre Livre.

This law declared that everyone born to a slave, after 1871, would be declared free, but provided time of service, being released with eight years (with compensation) or with twenty-one years (without indemnity).

This law was enacted to meet a series of interests of slave owners, but it was used often by abolitionist lawyers and rábulas (lawyer without academic training) in defense of enslaved. This performance in the law was one of the forms of popular resistance against the institution of slavery in our country. Another law created by slaveholders to meet their interests in a gradual transition was the Sexagenarian Law of 1885.

The abolitionist mobilization, in turn, was not reclusive to this. Between 1868 and 1871, 25 associations appeared that defended the abolition in different provinces of Brazil|2|. One of the names that was already involved with these associations was Luís Gama, a black lawyer who worked hard in defense of abolition.

The growth of the abolitionist cause began in the 1870s, but in the 1880s this was the most debated issue in the country. The growth of abolitionism is expressed in data that points out that, between 1878 and 1885, 227 abolitionist associations emerged in the country|3|. This number of associations helped to spread the cause publicly and made the country's popular classes begin to defend abolitionism.

Among these associations, the largest and most important of them was the Abolitionist Confederation, an association created by André Rebouças and José do Patrocínio. Historian Ângela Alonso alleges that the Abolitionist Confederation “coordinated propaganda on a national scale, grouping associations and triggering the liberation campaign”|4|.

Resistance against slavery also took place in “illegal” ways (according to the legislation at the time) and it was common for people to shelter escaped slaves and these abolitionist associations organized movements that stole slaves from their owners and took them to Ceará (where abolition took place in 1884). If you are interested in knowing more about this, we suggest reading this text: Caifazes and popular abolitionism.

These abolitionist groups created escape routes for slaves, disseminated pamphlets, published texts in defense of the cause in newspapers, organized conferences and public events, forged manumission papers, etc. Intellectualized groups, such as writers, lawyers and journalists joined the cause, but also popular groups, such as workers' associations.

The movement against slavery did not happen only by the free population of Brazil, but also had the support of fundamental involvement of slaves. According to historian João José Reis|5|, the action of slaves was fundamental, as it imposed limits on slave owners and openly contributed to the abolition of slavery in 1888.

Throughout the 18th century, but mainly from the 1870s onwards, slaves organized and rebelled against slavery. Among the forms of resistance are escapes that could be individual or collective, revolts that demanded improvements in their treatment and there were revolts that resulted in the death of slave owners.

the andrunaway slaves sheltered in quilombos which, in the second half of the 19th century, spread throughout the country, especially in regions such as Santos and Rio de Janeiro. In one of these quilombos – Quilombo do Leblon – the symbol of the abolitionist movement emerged in the 1870s and 1880s: the white camellia.

The white camellia was a flower cultivated by the quilombolas of Quilombo do Leblon and became a symbol of abolitionism in Brazil.

In that quilombo, slaves grew white camellias to sell and, over time, this flower became a symbol of the cause. This was the result of abolitionist propaganda and, according to historians Lilia Schwarcz and Heloísa Starling stated, “carrying a camellia in the buttonhole of your jacket or growing it in the garden at home was a gesture political"|6|. This gesture demonstrated that the person supported the abolitionist cause.

Slavery Abolition Day

The Lei Áurea was passed after Princess Isabel signed the law, on May 13, 1888.*

The adherence of different groups to abolitionism made the cause gain strength at the national level. This action, as we can see, mobilized the slaves themselves, had the support of different groups in society and took up space in the political debate. In 1887, the situation was unsustainable: slave revolts were spreading across the country and the authorities were no longer able to control them.

The abolitionists even called the population to arms to defend the abolitionist cause, and, in beginning of 1888, part of the political groups that defended slavery ended up joining the cause abolitionist. The project for abolition was proposed by the Conservative Party politician João Alfredo, and, after being approved by the Senate, it was taken to the regent of Brazil, the Princess Isabel signed the Golden Law, on May 13, 1888.

With the approval of the Lei Áurea, the people's festivities spread through the streets of Rio de Janeiro and lasted for days. The popular festivals did not only happen in Rio de Janeiro, but spread across the country and took place in places like Recife and Rio de Janeiro and in rural areas of the country.

Grades

|1| ALENCASTRO, Philip. Africa, Atlantic traffic figures. In.: SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz and GOMES, Flávio (eds.). Dictionary of slavery and freedom. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2018, p. 57.

|2| ALONSO, Angela. Political processes of abolition. In.: SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz and GOMES, Flávio (eds.). Dictionary of slavery and freedom. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2018, p. 359.

|3| Same, p. 360.

|4| Same, p. 360.

|5| REIS, Joao Jose. “We find ourselves in the field dealing with freedom”: black resistance in nineteenth-century Brazil. In.: MOTA, Carlos Guilherme (org.). Incomplete Journey: the Brazilian experience. São Paulo: Editora Senac, 1999, p. 262.

|6| SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz and STARLING, Heloísa Murgel. Brazil: A Biography. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015, p. 309.

*Image credits: Georgios Kollidas It is Shutterstock

By Daniel Neves

Graduated in History

Source: Brazil School - https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/historiab/abolicao-da-escravatura.htm