Gregory of Matos he was one of the best-known poets in the literature made during the 17th century, a period of Brazilian colonial culture. It's also the big expression of the baroque movement in Brazil and the patron of chair number 16 at the Academia Brasileira de Letras.

Many of his verses are acidic, satirical and reflect a critical posture to the colonial administration – excessively localist and bureaucratic – to the Brazilian nobility, to the clergy moralist and corrupt and who most made up the degraded colonial society, which earned him the nickname in mouth of hell.

Read too:Baroque in Brazil - the particularities of the occurrence of this movement on Brazilian soil

Biography

Son of two Portuguese noblemen, Gregório de Matos and Guerra was born inDecember 20, 1636 in Salvador (BA), then capital of the colony. He studied Humanities at Colégio dos Jesuitas and then left for Coimbra, where he graduated from law School and he wrote his doctoral thesis there, all in Latin.

![Portrait of the poet Gregório de Matos made in the 19th century by F. Brigit. [1]](/f/c3531ea2e4283a6300491eaa7c642385.jpg)

Still in Portugal, he held the positions of criminal judge and curator of orphans, but, ill-adapted to life in the metropolis, returnor to Brazil in 1683. In Bahia, the first Archbishop D. Gaspar Barata granted him the positions of vicar general (an occupation linked to the Episcopal Court, responsible for investigating crimes and for the administration of justice) and chief treasurer. However, his refusal to complete ecclesiastical orders prevented him from remaining in office.

He fell in love with the widow Maria de Povos, with whom he first lived in calm and until he fell into poverty. It was considered, in its time, a infamous man but an excellent poet. He fell into the bohemia, embittered, mocking and satirizing everything and everyone, especially those who had power, whom he annoyed so much that he was deported to Angola in 1685 and banned from returning to Brazil until 1694. He settled in Recife (PE), in 1696, where he ended up passing away on November 26 of the same year.

Read too: Brazil Colony, period of history in which Gregório de Matos lived

Do not stop now... There's more after the advertising ;)

literary features

The work of Gregório de Matos has two aspects: the satirical, composed of the mocking verses by which he became known and which earned him the nickname Boca do Inferno, and the lyrical-loving, whose poems are divided between sacred themes It's from sensual love. The poet reverberates in his work literary characteristics of the Barrocco, as the moralization of earthly life, the character counter-reformist, dualism and human anguish.

Gregório de Matos wrote sonnets, blocks, sextiles and poems in different forms, always rhyming and generally following the regular metric scheme, in force at the time (and which facilitated memorization). It is us sonnets which is mainly to baroque influence of his work, with syllogisms, abundant use of speech figures, word games and oppositions (sacred-profane, love-sin, sublime-grotesque, etc.).

Construction

According to professor and researcher João Adolfo Hansen, one of the main specialists in the literature of the Brazilian colonial period, he is not known no manuscript in his own hand written by Gregório de Matos. All of his texts, like other contemporary poets, were collected in compilations made by your admirers, so that the author himself edited nothing in life.

In the 17th century, the circulation of books was scarce and often prohibited or censored, and there were few literate citizens in Brazil. The poems of Gregório de Matos were, as a rule, written in pamphlets, that circulated through the city of Salvador. These pamphlets were collected by some collectors and then stitched together into a type of document known as a codex. The satirical verses, on the other hand, were commonly pasted (with cassava flour glue) on the doors of churches and those who knew how to read would declaim them – easily memorized, they served to inspire new poems.

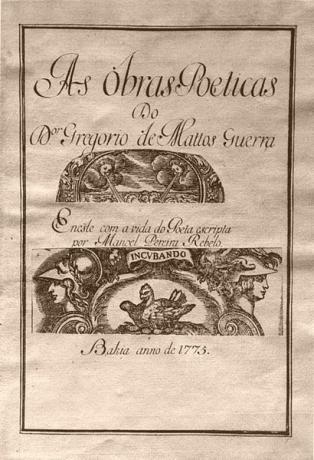

There are more than 700 texts attributed to Gregório de Matos, but there is no way of confirming his authorship. The publication of a first compilation of his verses, titled The Life of the Excellent Lyrical Poet, Doctor Gregório de Matos e Guerra, made by the Bahian Manuel Pereira Rabelo. This collection of poems was, however, forgotten until 1841, when Canon Januário da Cunha Barbosa, member of the recently founded Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, he published two comic poems of this compilation.

The so-called Rabelo Codex is probably the main source for the publication of chosen poems, work published in 2010 with selection, preface and notes by Professor José Miguel Wisnik. Also worth mentioning is the Gregório de Matos Collection, organized by João Adolfo Hansen and Marcello Moreira, composed of five volumes bringing together the poetry attributed to the author from the Codex Asensio-Cunha.

Read too:Arcadianism – post-baroque literary movement

Topics covered and poems

There are three main themes addressed by Gregório de Matos: love poetry, religious poetry and satirical poetry.

→ Lyric Loving Poetry

Love is approached by Gregório de Matos frequently from the flesh/spirit duality, in which carnal love represents the fleeting temptation of sexual passion, understood as sinful by Catholicism, sowing a feeling of guilt and an anguish perception of the instability and inconstancy of matter – everything ends, the body deteriorates, human existence is finite. The beauty of the female figure is often associated with elements of nature.

In the poem below, entitled "The D. Angela", we can clearly see these characteristics: the evocation of feminine beauty compared to the flower, element of nature, in a play on words with the girl's name, which, in turn, refers to the divine presence of the figure angelic. However, the poet's conclusion, “you are an Angel who tempts me, and does not keep me”, reminds us that beauty, although it has divine, angelic traits, is the result of the temptation of the flesh.

The D. Angela

Angel in the name, Angelica in the face,

This is to be a flower, and an Angel together,

Being Angelica Flower, and Angel Florent,

In whom, if not in you?

Who would see a flower that had not cut it

With a green foot, with a flowering branch?

And whoever an Angel turns so bright,

That by his God, he had not worshiped him?

If as an Angel you are of my altars,

You were my custodian, and my guard,

Delivered me from diabolical misfortunes.

But I see, how beautiful, and so gallant,

Since Angels never give regrets,

You are an Angel, who tempts me, and does not keep me.

There are also several love-lyric poems based on a reflective and meditative posture of the poet, writing in games of meanings in light of the dualism characteristic of the Baroque period: life and death, ferocity and compassion.

The poet wandered through those retreats philosophizing in his misfortune without being able to detach the harpies of his just feeling

Who saw bad like mine without active means!

For in what sustains me, and mistreats me,

It's fierce, when death stretches me,

When life takes me away, it's compassionate.

Oh my high reason to suffer!

But oh my ungrateful pity martyrdom!

Once fickle because it kills me,

Often cruel, as it has me alive.

There is no longer any remedy for trust;

That death to destroy has no breath,

When life becomes warped, there are no changes.

And want my evil doubling my torments,

May you be dead to hope,

And that walks alive for the feelings.

→ religious poetry

The Catholic theme is present in several verses by Gregório de Matos, always imbued with a counter-reformist spirit also very characteristic of the baroque. It relies on the features of the movement: matter/spirit duality, inconstancy (and dangers) of earthly life, anguished perception of mortality and of human smallness before the divine greatness, salvation/sin, submission to the church, contrition and repentance of sins.

We can see these characteristics in the poem below, "On Ash Wednesday", in which the poet evokes a specific day in the Roman Catholic calendar to expound his ideas, glorifying The divine grandeur and its power (representation of the perennial, the spiritual, the eternal) before the ephemeral human existence (mortal, non-lasting and fickle), condemning the villains and sins of men. The low, small vessel, is used as a figure of speech to represent the dangers and temptations of life human, hostage to the "seas of vanity", in opposition to the solid land of the Catholic faith, representing the solidity of salvation divine.

the day of ash wednesday

that you are earth, man, and on earth you shall become,

God reminds you today for his Church;

From dust it makes you a mirror, in which to see yourself

The vile matter from which I wanted to form you.

Remember God that you are dust to humiliate you,

And as your low always weakens

In the seas of vanity, where he fights,

Puts you in sight of the land, where to save yourself.

Alert, alert, therefore, that the wind screams.

The vanity blows and the cloth swells,

In the bow the land has, softens and irons.

All dead wood, low human,

If you are looking for salvation, take land today,

That the land of today is a sovereign port.

→ satirical poetry

It is for this category of poems that Gregório de Matos is best known and acclaimed in the national literary canon. Biting critic of colonial society, no one escaped his scorns: Brazilian noblemen who prided themselves on their Portuguese blood (but they were mestizos), clerics who defended morals and the good customs (but they were corrupt, libidinous, lazy and sinful), authorities who abused power (colonial and centralized), even blacks, mestizos and citizens common. with your incisive vocabulary and compositions of burlesque rhymes, the satirical poems mocked and mocked everything and everyone, denouncing the vices of the colony.

See some excerpts from the 100 verses of the poem “The poet has already embarked for his exile, and set eyes on his ungrateful homeland sings farewell to him from the sea", written, as the title says, when Gregório de Matos was expelled from Brazil. In it, the poet attacks the entire Bahian capital and the formation of an unscrupulous colony; against the planters; against the Portuguese and the Brazilians – the latter, workhorses supporting Portugal –; against the colonial nobility proud of a racial purity it does not possess, hypocritical and flattering, and which lives by being flattered as well.

The poet has already embarked for his exile, and set his eyes on his ungrateful homeland, he sings farewells from the sea.

Goodbye Beach Goodbye City

and now you will owe me,

Rogue, bid me goodbye,

to whom I owe the demo to give.

that now, that you owe me

bid you goodbye, like someone falling,

since you're so down,

that not even God will want you.

Goodbye People, goodbye Bahia,

I mean, you infernal bastard,

[...]

go visit friends

in each one's mill,

and eating them by one foot,

never take your foot out of there.

That Brazilians are beasts,

and will be working

all life to keep

maganos of Portugal.

[...]

In Brazil the nobility

in the good blood it is never,

not even in the proper procedure,

as soon as it can be?

It consists of a lot of money,

and it consists of saving it,

each one keep it well,

to have to spend badly.

It consists of giving it to magicians,

that they know how to flatter you,

saying, which is descendant

of the Vila Real house.

[...]

We can see that the condemnation of exile in Angola comes from a series of verses against the governors and citizens of Bahia, as in the excerpts presented below from the poem “Redefining the poet's bad ways of working in the governance of Bahia [...]”, in which he makes a list of social ills that plagued the colony and its capital, Savior. No one escapes: from rulers to slavers, passing through the blacks, the flawed judicial system, the clergy corrupt and ambitious, comparing Bahia to a sick and dying body, given the collection of ills of which suffers.

The poet again defines the bad ways of working in the governance of Bahia, especially in that universal hunger that the city suffered

What is missing in this city... Truth

What more for your dishonor... Honor

There's more to be done... Shame.

The demo to live exposes itself,

as much as fame exalts,

in a city, where

Truth, Honor, Shame.

Who put her in this partnership... Business

What causes such perdition... Ambition

And the biggest part of this madness... Usury.

remarkable misadventure

of a foolish people, and Sandeu,

that you don't know, that you lost it,

Business, Ambition, Usury.

What are your objects... black

Do you have other more massive goods... mestizos

Which of these are you most grateful... Mulattoes.

I give the demo the fools,

I give the demo we asnal,

what esteem for capital

Blacks, Mestizos, Mulattoes.

[...]

And that justice protects... bastard

Is it distributed free... sold

What is it that frightens everyone... Unfair.

God help us, what it costs,

what El-Rei gives us for free,

that justice walks in the square

Bastard, Sold, Unfair.

What goes for the clergy... Simony

And for the members of the Church... Envy

I took care, what else was there... Nail.

Seasoned Periwinkle"

at last that in the Holy See

what is practiced is

Simonia, Envy, Nail.

[...]

Is the sugar gone... downloaded

And the money died out... went up

Have you already convalesced... Died.

Bahia happened

what happens to a patient,

falls into bed, evil grows on him,

Down, Up and Died.

by Luiza Brandino

Literature teacher