Dialectics has its origins in ancient Greece and means the "way between ideas". It consists of a method of seeking knowledge based on the art of dialogue. It is developed from distinct ideas and concepts that tend to converge towards secure knowledge.

From the dialogue, different ways of thinking are evoked and contradictions emerge. Dialectics elevates the critical and self-critical spirit, understood as the core of the philosophical attitude, questioning.

The origin of dialectics

The origin of dialectics is a matter of dispute between two Greek philosophers. On the one hand, Zeno of Elea (ç. 490-430 a. C.) and, on the other hand, Socrates (469-399 a. C.) has attributed to itself, the foundation of the dialectical method.

But, without a doubt, it was Socrates who made famous the method developed in the ancient philosophy, which influenced the entire development of Western thought.

For him, the method of dialogue was the way in which philosophy developed, constructed concepts and defined the essence of things.

Nowadays, the concept of dialectic has become the ability to perceive the complexity and, more than that, the contradictions that constitute all processes.

The history of dialectics

From the importance given to the dialogue proposed in the socratic method, the dialectic, for a period, lost strength. Many times, it was configured as secondary or as an accessory method to the scientific method.

Mainly, during the Middle Ages, knowledge was based along a stratified social division. Dialogue and the clash of ideas was something to be repressed, not encouraged. Dialogue was not understood as a valid method for acquiring knowledge.

With the Renaissance, a new reading of the world that denied the previous model made dialectics return to being a respectable method for knowledge.

The human being came to be understood as a historical being, endowed with complexity and subject to transformation.

This conception is opposed to the medieval model that understood man as a perfect creature in the image and likeness of God and, therefore, immutable.

This complexification brings with it the need to resort to a method that would account for the movement in which human beings found themselves.

Since the Enlightenment, the apogee of reason, made dialectics a method capable of dealing with human and social relations in constant transformation.

It was the Enlightenment philosopher Denis Diderot (1713-1784) who realized the dialectical character of social relations. In one of his essays he wrote:

I am the way I am because it was necessary for me to become that way. If you change the whole, necessarily I will also be changed."

Another philosopher responsible for strengthening the dialectic was Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). He realized that society was unequal, often unfair, and made up of contradictions.

Based on this thought, Rousseau started to propose a change in the social structure that could be in favor of the majority, and not look after the interests of a minority.

Thus, the "general will" preached by Rousseau goes further and preaches the convergence of ideas to achieve the common good.

These ideas echoed across Europe and found their materialization in the French Revolution. Politics and dialogue served as principles for establishing the new mode of government.

With Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), the perception of setbacks is related to the proposal to establish limits for human knowledge and reason.

With this, Kant believed he had found a solution to the problem between rationalists and empiricists, the conception of the human being as a subject of knowledge, active in understanding and transforming the world.

Thoughts without content are empty; intuitions without concepts are blind.

From Kantian thought, the German philosopher Hegel (1770-1831) stated that the contradiction (the dialectic) is not found only in the being of knowledge, but constitutes the objective reality itself.

Hegel's Dialectic

Hegel realizes that reality restricts the possibilities of human beings, who are realized as a force of nature capable of transforming it through the work of the spirit.

The Hegelian dialectic is made up of three elements - thesis, antithesis and synthesis.

1. Thesis

The thesis is the initial statement, the proposition that presents itself.

2. Antithesis

The antithesis is the refutation or negation of the thesis. It demonstrates the contradiction of what was denied, being the basis of dialectics.

3. Synthesis

The synthesis is composed from the logical convergence (dialectical logic) between the thesis and its antithesis. This synthesis, however, does not assume a concluding role, but as a new thesis capable of being refuted, continuing the dialectical process.

Hegel shows that work is what separates humans from nature. The human spirit, based on ideas, is able to dominate nature through work.

Let's look at the example of bread: nature offers the raw material, wheat, human beings deny it, transforms wheat into pasta. This dough after roasting becomes bread. Wheat, like the thesis, remains present, but takes another form.

Hegel, as an idealist, understands that the same happens with human ideas, they advance dialectically.

The true is the whole.

Marx's dialectic

the german philosopher Karl Marx (1818-1883), a scholar and critic of Hegel, stated that Hegelian thought lacks a totalizing vision that takes into account other contradictions.

Marx agrees with Hegel on the aspect of work as a humanizing force. However, for him, work from a capitalist perspective, post-industrial revolution assumes an alienating character.

Marx builds a materialist thought in which the dialectic takes place from the class struggle in its historical context.

For the philosopher, dialectics needs to be related to the whole (reality) that is the history of humanity and the class struggle, as well as the production of tools for the transformation of this reality.

Philosophers have limited themselves to interpreting the world; the important thing, however, is to transform it.

This larger totality is not completely defined and finished, as it is limited to human knowledge. All human activities have these dialectical elements, what changes is the scope of the reading of these contradictions.

Human activity is composed of several totalities with distinct ranges, the history of humanity being the broadest level of dialectical totalization.

Dialectical consciousness is what allows the transformation of the whole from the parts. Education assumes that the reading of reality is composed of at least two contradictory (dialectical) concepts.

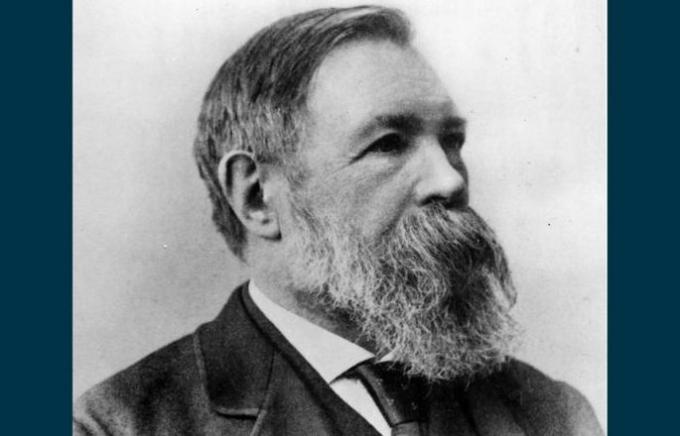

Engels' Three Laws of Dialectics

After Marx's death, his friend and research partner Friedrich Engels (1820-1895), from the ideas present in The capital (first book, 1867), sought to structure the dialectic.

For this, it developed its three fundamental laws:

- Law of passage from quantity to quality (and vice versa). Changes have different rhythms and may change in quantity and/or quality.

- Law of interpretation of opposites. Aspects of life always have two contradictory sides that can, and should, be read in their complexity.

- Law of denial of denial. Everything can, and must, be denied. However, the denial does not stand as a certainty, it must also be denied. For Engels, this is the spirit of synthesis.

According to the materialist conception of history, the determining factor in history is ultimately the production and reproduction of real life.

Leandro Konder and dialectics as 'dragon seed'

For the Brazilian philosopher Leandro Konder (1936-2014), dialectics is the full exercise of the spirit critical and the method of questioning capable of dismantling prejudices and destabilizing thought current.

The philosopher uses the thought of Argentine writer Carlos Astrada (1894-1970) and states that dialectics it is like "seed of dragons", always contesting, capable of disturbing all the most structured theories. And the dragons born of this constant contestation will transform the world.

Interested? Here are other texts that can help you:Dragons seeded by dialectics will frighten many people around the world, they may cause riots, but they are not inconsequential rioters; their presence in people's consciousness is necessary so that the essence of dialectical thought is not forgotten.

- Rhetoric

- The concept of alienation in sociology and philosophy

- Marxism

- social division of labor

- Concept of added value for Marx

- Questions about Karl Marx