THE Constitutionalist Revolution it was a civil war that happened in Brazil, in 1932, as a consequence of the political disagreement between the São Paulo state it's the Federal government. This revolt was motivated by São Paulo's dissatisfaction with the Getúlio Vargas government due to the lack of a Constitution and the failure to hold a presidential election in Brazil.

With a balance of up to three thousand dead, the Constitutionalist Revolution is understood as a reaction by São Paulo to the new political arrangement that was established in the country since the 1930 revolution. Dissatisfied with the loss of power and autonomy, the Paulistas rebelled and, in July 1932, began an armed movement against Vargas.

see more: Pests column - movement in opposition to oligarchic politics in Brazil

Context

The Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932 is a direct consequence of the Revolution of 1930 - the armed uprising that toppled Washington Luís from the presidency, prevented Júlio Prestes from taking office, and led Getulio Vargas to the position of president of Brazil. With that, the GovernmentProvisional, that is, a government was set up to lead the transformations in the country until the promulgation of a new constitution and the holding of a new election for president.

Vargas, despite being provisionally named president, has openly demonstrated that had no intention of relinquishing power. Between 1930 and 1932, its measurescentralizing were noticeable, and this began to annoy the political and economic elite of São Paulo. In addition, existing conflicts between lieutenants and the liberals contributed to reinforcing São Paulo's dissatisfaction.

At that time, the great demand made by São Paulo society, especially by the middle class in that state, was the enactment of a new constitution and the holding a new presidential election. The interests of the Paulistas went against the interests of the tenentistas, a group that defended the application of a centralizing policy.

It was this mismatch between the interests of Vargas, the tenentistas and the liberal constitutionalists in São Paulo that led São Paulo to an armed revolt. Vargas, in turn, tried to get around the political crisis that was taking shape in Brazil at that time. In February 1932, a new Electoral Code, and, in March, a decree was published calling for an election for formation of a Constituent in early 1933.

Finally, there was the issue involving the appointment of interventores (presidents of state) to govern São Paulo. In November 1930, Vargas named João Alberto Lins de Barros, a lieutenant, as interventor. This was part of Vargas' effort to maintain the support of the tenentistas, a group that guaranteed his support in power.

The liberal constitutionalist paulistas, however, did not like the appointment of “outsiders” to govern the state, and began to demand the appointment of a paulista and civil interventor. Later, Vargas made the appointment of other people to the Interventory of the State of São Paulo, but the liberals they remained dissatisfied.

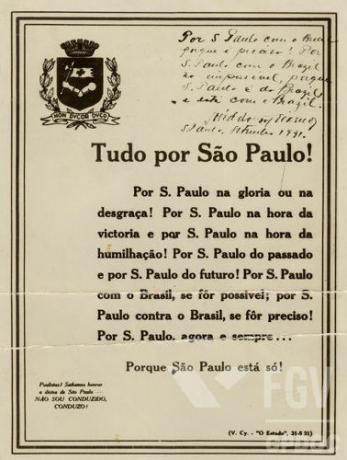

The São Paulo mobilization against the Federal Government was led by the Republican Party of São Paulo (PRP), and, from the beginning of 1932, the São Paulo Democratic Party (PD) joined the chorus of the dissatisfied. The PRP's stance against Vargas clearly demonstrates that this opposition was an attempt by the state's political elite to try to regain power that had been lost in 1930.

Accessalso: Olga Benário Prestes: the life of one of the most memorable people of the Vargas Era

Mobilization in São Paulo

In February 1932, he was trained in São Paulo to São Paulo Single Front (FUP), a group that brought together members of the PRP and the PD. With its emergence, the possibility of an armed uprising against the government began to be debated. At the same time, members of the former Minas Gerais and Rio Grande do Sul oligarchy began to express their irritation with Vargas. This gave encouragement to São Paulo, who began to hope to have both in case of war against Vargas.

Even with all the concessions made by the head of state, the political climate in São Paulo was one of unrest. Reports made by Osvaldo Aranha for the Federal Government they demonstrated the atmosphere of agitation and incitement against Vargas. In May 1932, the trigger for the beginning of the armed uprising in São Paulo happened.

On May 23, young people from São Paulo went murdered in a confrontation with forces supporting Vargas. The initials of the names of four of them gave rise to a secret group that carried out the preparation for war: the MMDC — referring to Martins, Miragaia, Drausius and Camargo.

The mobilization against Vargas was great, mainly in the state capital. Historians Lilia Schwarcz and Heloísa Starling demonstrate the level of mobilization: thousands of volunteers joined the uprising, factories were transformed into war industries, doctors volunteered and even jewelry (approximately 90,000 gold rings) were donated to fund the purchase of weapons|1|.

Raise armed

![Airmen from São Paulo who fought against the Federal Government in 1932. [1]](/f/0bbd02a5aa41bd5f78a09f3e41e3c2ab.jpg)

The uprising in São Paulo was triggered on the day July 9, 1932, under the leadership of the interventor from São Paulo, PeterinToledo, and the general IsidoreDayslopes. The expected support from miners and gauchos against the Vargas government ended up not happening.

Historian Thomas Skidmore points out that the reason for this was that both states were unprepared for the uprising and therefore chose not to get involved. With that, gauchos and miners joined the federal forces|2|. Mention may also be made of the fact that, despite being dissatisfied, Gauchos and miners were afraid to rise up against the government they had helped to establish two years earlier.

Vargas handed over the Army command to Goes Monteiro, who tried to take actions to prevent any kind of uprising from happening in the capital. Goés Monteiro also acted to interrupt the march of São Paulo troops towards Rio de Janeiro. During the war, planes were used to bomb areas dominated by the rebellious Paulistas.

Federal troops attacked the Paulistas by sky, land and air. The lack of resources was essential for the Paulistas to be defeated. Its troops were surpassed by the Federal Government in number of soldiers, quantity of weapons and ammunition. As the conflict spread, the possibility of an attack on the city of São Paulo became more real.

Cornered and without the resources to continue the war, the Paulistas signed their surrender to the Federal Government in October 1, 1932. The uprising in São Paulo lasted less than 90 days and caused the death of thousands of people.

Accessalso: The main events of the Estado Novo (1937-1945)

Results

Despite the military defeat, the Vargas' reaction to São Paulo was reasonably mild. Vargas had understood from the conflict that it was not possible to sustain a centralized government with dissatisfied São Paulo elites. Thus, he sought to put an end to any feeling of opposition among the Paulistas, giving them a series of concessions.

However, also took steps to punish some of those involved with the uprising. As Lilia Schwarcz and Heloísa Starling demonstrate, Vargas “arrested the rebels, expelled army officers, impeached civil rights of the main people involved in the uprising, sent the political and military leaders of the state into exile” etc.|3|.

Thereafter, Vargas gave assurances of what he had assumed before the armed uprising and guaranteed the holding of presidential election and of the formation of a Constituent. From this Constituent the 1934 Constitution, a very democratic and advanced letter for the time. Vargas also appointed a São Paulo and civilian interventor — Armando Salles — to the liking of the local population and assumed the debts made by the Paulistas during the war.

Grades

|1| SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz and STARLING, Heloísa Murgel. Brazil: a biography. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015. P. 364.

|2| SKIDMORE, Thomas E. From Getúlio to Castello (1930-1964). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2010. P. 5051.

|3| SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz and STARLING, Heloísa Murgel. Brazil: a biography. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015. P. 366.

Image credits

[1] FGV/CPDOC