THE sabinada was one of the provincial revolts that took place in Brazil during the Governing Period. It took place between 1837 and 1838 and was the result of the dissatisfaction of the middle classes in Salvador, mainly. The movement lasted five months, and the government's repression of those involved was great.

Read too: Cabanagem: one of the biggest revolts that took place in the Regency Period

Governing Period

Sabinada was a provincial revolt that happened in the Regency Period, that is, the transition period of the reign of D. Peter I to reign of D. Pedro II in Brazil. This regency phase happened because, when D. Peter I renounced the throne, his son was still a minor and could not be crowned emperor.

As provided for in the Brazilian Constitution (1824), the country should be governed by regents until the son of D. Pedro I was of the minimum age to assume the throne. One of the great brands in Brazil during the Regency Period was the Intense dispute between conservatives and liberals in Brazilian politics.

The Regency Period also brought something new to the country: for the first time Brazil, as an independent country, guaranteed a certain autonomypoliticsto your provinces. However, the lack of an emperor on the Brazilian throne, added to Brazil's socioeconomic problems and political disputes in the provinces, created an explosive situation.

This period was the phase of a federalist experience (a system that guaranteed the autonomy of the provinces), but it was also the period of provincial revolts. As mentioned, these revolts were a sum of popular dissatisfaction and political disputes between elites, but also contained the defense of republican ideals.

Accessalso: Beckman's Revolt — the popular revolt that took place in Maranhão

What were the causes of Sabinada?

THE Bahia in the 1830s was a place of great political turmoil. This Brazilian province had gone through major events, such as the Bahia Conjuration and the Wars of Independence. In the 1830s, two other important events still took place: the federalist uprising in 1832 and the Malês revolt in 1835.

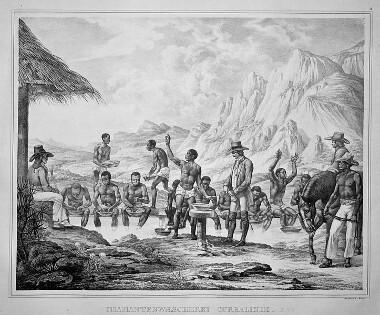

The federalist uprising took place in the Recôncavo Baiano and, on that occasion, federalists dissatisfied with the large presence of Portuguese in Bahia tried to establish a federalist government in the region. The Malês Revolt, on the other hand, involved enslaved Africans who were practitioners of Islam and was marked as the greatest slave revolt in Brazilian history.

We realized, therefore, that Bahia had gone through a lot of political and social unrest, and the context of the Regency Period contributed to this unrest continuing. Historian Keila Grinberg says that, in the 1830s, the president of the province was already aware of the existence of a “disorganizing party”|1|.

THE circulation of ideas in defense of federalism and the republic it happened in dissatisfied groups. In addition, in 1837, a strengthening of conservatives in Brazilian politics began, and the policy of decentralization of the The power practiced by liberals began to wane—Father Feijó's resignation from the regency of Brazil was a clear sign of that.

In addition to the political issues, there was also an economic issue related to the weakening of the local economy, mainly because of the sugar economy crisis. Finally, there was dissatisfaction with the large presence of Portuguese in Bahia, mainly because they occupied important positions in the administration of the province and in commerce.

This dissatisfaction in Bahia mainly affected the classesaverages, and the most dissatisfied groups were "military, doctors, lawyers, journalists, civil servants, artisans and small merchants"|2|.

One of the most dissatisfied groups in this context were the military, mainly the black military, who were irritated by the injustices in the corporation and the difficulty of promotion. The military, in general, also demanded a salary increase and were against the calls for them to go to fight in southern Brazil against the rags.

All these issues led the Salvadorian middle class to rebel in the year 1837. The first step was taken by the military.

Start of revolt

the sabinada started with araisemilitary what happened in November 6, 1837. On that day, the Artillery Corps located at Fort São Pedro rebelled and took over this military installation. The next day, civilians joined the rebel military and together they went to the center of Salvador.

There the Sabinos (as the rebels of that revolt became known) mobilized the police and, together, took control of Palace Square. The Bahia authorities fled the capital and settled in the Reconcavo Baiano region.

The Sabinos then went to the City Council of Salvador and began parliamentary activities, drawing up a manifest, which was signed by 105 men|3|. In this manifest, the official separation from Bahia in relation to the government of Rio de Janeiro and announced that Bahia would become an independent state, which would have elections as soon as possible.

The new government had as president Inocencio da Rocha Galvão, a lawyer who was in exile in the United States and who never effectively took possession of that position. The doctor and journalist FranciscoSabino, the great leader of the Sabinada (from his surname came the name of the revolt), was chosen as secretary of Bahia.

Lastly, João Carneiro da Silva Rego, a lawyer and owner of lands and slaves, was appointed as vice president to make up for Rocha Galvão's absence. We realized, therefore, that the names indicated in the revolt's leadership were people linked to this dissatisfied middle class, and the revolt, at first, had a characterseparatist.

However, this Sabinada separatism was called into question just four days after the manifesto was drawn up. Some of the members of the revolt feared that the movement would weaken, so the vice president received a request from 30 citizens for the original manifesto to be modified.

This made the separatism of the Sabinada become transitory, because a new document announced that the Bahia declared his separation until Pedro de Alcântara reached his majority and was crowned emperor of the Brazil. This new manifesto was approved on November 11, 1837.

At Bahia elites did not join à revolt started in Salvador and gave their support to the authorities who had fled the city and settled in the Recôncavo Baiano. The mill owners joined their efforts with the provincial government to overthrow the sabinos. There was also no popular adhesion, and part of the Salvadoran population left the city, fearing that the revolt would bring violence and hunger to the Bahian capital.

The resistance forces that were forming on the outskirts of Salvador decided not to invade the city. Keila Grinberg says this happened because they didn't have enough weapons to invade it, so decided to fenceAllah to prevent food from arriving. Salvador was also surrounded by the sea. That siege lastedfive months.

Accessalso: Inconfidência Mineira: the revolt generated by dissatisfaction with taxes

End of the Sabinada

On March 14, 1838, the city of Salvador was in a very complicated situation due to the lack of food, and the Sabinos' revolt was weakened. An attack by provincial government forces took place that day, leaving about 1800 dead by the Bahian capital|4|. There was destruction, and fires spread throughout Salvador as a result of the battles.

The surrender took place on March 15, and the Sabinos asked for clemency, but their demand was not met. Of the approximately 1800 dead, 1258 of them were rebels, almost three thousand people were arrested and there were those who were sent to Rio Grande do Sul to fight in the Army, while others were sent to Rio de Janeiro.

The freed blacks who participated in the Sabinada were exiled to Africa; others were sent to Fernando de Noronha. Francisco Sabino, in turn, was sentenced to death by hanging along with six other people. However, Sabino was pardoned, and his sentence was changed to exile to the Rondônia region, but he was sent to Cuiabá.

Grades

|1| GRINBERG, Keila. Sabinada (1837). In.: SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz and STARLING, Heloisa Murgel. Dictionary of the Republic: 51 critical texts. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2019, p. 369.

|2| Idem, p. 371.

|3| Idem, p. 370.

|4| SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz and STARLING, Heloísa Murgel. Brazil: A Biography. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015, p. 259.

Image credits

[1] Thiago Santos and Shutterstock