O Civil-Military Coup of 1964 is the name given to the coup movement that, between March 31 and April 9, 1964, took power, subverting the existing order in the country and starting the Military dictatorship, a dictatorial regime that extended in Brazil from 1964 to 1985 and was characterized by censorship, kidnappings and executions committed by agents of the Brazilian government. During the coup carried out in 1964, the then inaugurated president, João Goulart, was removed from his post.

Historical context

O 1964 coup was the result of a coup political articulation carried out by civilians and military in the passage from 1961 to 1962. It is important to clarify that, despite this conspiracy having actually emerged in 1961, the Fourth Brazilian Republic it was marked by different attempts at subversion of the order carried out by the UDN.

The path that led to the 1964 coup began to be followed with the possession of João Goulart (Jango) in 1961.

Several obstacles were created for Jango's inauguration as president, who only took over because a parliamentary system that reduced the Executive's powers was hastily implemented.Because of Jango's close relationship with Brazilian unionism, society's conservative groups they saw the Gaucho politician with extreme suspicion and often accused him of being a communist by the conservatives. The political crisis of the Jango government was also strengthened by reforms that were defended by the government – the Basic Reforms.

Jango's inauguration was not only a nuisance for conservative groups in Brazil, but also annoyed the government of United States, which considered João Goulart a politician “too far to the left” of what was expected of a president Brazilian.

Two actions by Jango's government increased this opposition from the American government, which started to finance coup movements in Brazil. The first action was the 1962 Profit Remittances Act, which prevented multinationals from sending more than 10% of their profits abroad. The second measure that the Americans disliked was the continuation of Brazil's independent foreign policy and practiced by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, San Tiago Dantas.

With that, from 1962 onwards, the United States began to actively finance conservative groups and politicians in Brazil. Two groups that received extensive American funding became known as the “Ipes-Ibad complex”, with Ipes being the Institute for Research and Social Studies, and Ibad the Brazilian Institute of Action Democratic.

Ibad was even the target of a CPI in 1962 because it received millions from the US government to fund the campaign of more than 800 politicians during that year's elections. The supported politicians were conservative politicians, and the objective was to create a parliamentary front that would block João Goulart's government in every way. Under Brazilian law at the time, this type of financing was illegal.

Ipes, on the other hand, was a group that played a decisive role in the success of the civil-military coup in 1964. In its public facade, Ipes acted as an institution that made intellectual production of books and documentaries, but the Ipes' secret role in Brazil's political framework is summarized by historians Lilia Schwarcz and Heloísa starling:

[…] Ipes acted against Goulart with a two-pronged policy. The first was the preparation and execution of a well-orchestrated government destabilization effort that included funding a propaganda campaign. anti-communist, fund anti-government public demonstrations and support, including in the financial sphere, opposition or far right1.

THE destabilization of Jango's government it was also largely carried out by the Brazilian press. The large circulation newspapers in Brazil united in a coup-like articulation that received the ironic name of Rede da Democracy (Democracy Network). The mobilization for the press coup was based on the following reading of the Brazilian political reality:

[…] newspapers became key players in the conspiracy from the end of 1963 onwards. Traditionally linked to the liberal-conservative line, the large Brazilian press consolidated the reading that the country was heading towards communism and subversion at the heart of power, that is, the presidency of the Republic2.

Read too: Difference between Right and Left

political radicalization

The ongoing conspiracy against João Goulart's government was the result of the fear of conservative groups with the rise of social movements, such as the movements of peasants, workers and students. Brazilian society was ideologically split between right and left, and one of the main targets of debate was the Basic Reforms.

At Basic Reforms they were a program stipulated by the Jango government that created an agenda and promoted a debate about structural obstacles in Brazilian society. They stipulated agrarian, tax, electoral, banking, urban and educational reform. Among all these proposals, the one that had the most advanced discussion in Brazilian political frameworks was the agrarian one.

THE land reform it dominated the national political debate from March to August 1963 and divided left and right. Peasant workers groups were formed and started to invade rural properties and to pressure the government to carry out the reform – even if by force. The owners, in turn, were against agrarian reform.

The proposal defended by the left stipulated that lands with more than 500 hectares that were unproductive would be the target of reform and that the expropriation of these lands would be carried out through indemnification of public debt bonds to be redeemed in the long term. deadline. The right, on the other hand, even accepted negotiations, but defended that agrarian reform should take place in accordance with the constitutional mechanisms, that is, upon payment of indemnity in cash and in cash according to the value of Marketplace.

This made the debate stall, and the failure to carry out agrarian reform aggravated the situation. Property invasions spread to different parts of Brazil. In addition, because of the wear and tear generated by the debate, Jango's parliamentary base linked to the PSD turned to the udenista opposition.

The difficulties of the Jango government increased with the intransigence of many groups on the left who wanted to carry out the Basic Reforms at all costs. This wing had the great name LeonelBrizola – João Goulart's brother-in-law, he had been governor of Rio Grande do Sul and, as of 1963, he became Federal Deputy for Guanabara.

This radical left action in defense of the Basic Reforms was exploited by the groups that articulated the coup. Thus, a speech spread across the country:

To justify a possible coup from the right, the idea of a coup from the left in the making was increasingly widespread. […] the trick of the right was to build equivalence between the reformist agenda that called for more social justice and more democracy, […] and a blow to freedom and democracy itself. This assertion led to a logical conclusion: the eventual coup by the right would, in fact, be merely reactive, therefore, legitimate defense of democracy and of “Western and Christian” values against the “radicals” of the left3.

The great paradox of this whole situation was that, even with the coup speech articulated by the press, civil and military groups, popular support for João Goulart's government was consistent. Data from Ibope for March 1964 indicate that 45% considered the current government “good” or “great”, and the voting intentions for a possible candidacy of Goulart for the presidential race in 1965 were of 49%4.

Read too:What is a coup d'état?

Jango's weakening

At the end of 1963, the situation in Brazil was chaotic. Peasants and urban workers were in revolt, the left demanded the expansion of reforms and defended a more energetic posture of the government, and the rights articulated with the Armed Forces for the seizure of power. In this context, João Goulart showed signs of weakness.

On September 12, 1963, the Sergeants' Revolt. This revolt was motivated by the dissatisfaction of the sergeants, who had been prohibited by the Federal Supreme Court (STF) from occupying positions in the Legislative. Rebel sergeants seized government buildings in Brasilia, but they were quickly contained, and the situation was brought under control. As no punitive action was taken by Jango, the government conveyed an air of impunity to a certain wing of the Armed Forces if there were other rebellions.

The second show of weakening occurred in October 1963, when João Goulart presented to Congress a proposal for a decree of state of siegefor 30 days. There is a lot of divergence in the historiography about this measure taken by Jango.

American historian Thomas Skidmore claims that Jango had been induced by his military ministers to intervene against violence caused by social movements and to intervene in the State of Guanabara because of statements by Carlos Lacerda against the military Brazilians5. Journalist Elio Gaspari treats this as an attempted coup by João Goulart6.

The proposal was rejected by lawmakers from all major parties (UDN, PSD and PTB). Three days later, Jango withdrew the proposal from Congress. The sum of the two events deeply shook Jango's image.

March 1964 and the coup

THE situation in Brazil remained extremely unstable and, in March 1964, the actions that defined the country's destiny were taken. The conspiracy of the far-right groups was in full swing, and an action by Jango unleashed the coup in Brazil in advance. On March 13, 1964, the Central do Brasil rally.

This rally mobilized from 150,000 to 200,000 people. In it, João Goulart reassumed his commitment to carrying out the Basic Reforms. Jango's speech implied that the president had abandoned the conciliation policy and that he would defend the Basic Reforms with the social movements.

The rconservative action was immediate and took place on the streets on March 19 with the Family March with God for Freedom. This march mobilized more than 500 thousand people in São Paulo against communism and demanding the intervention of the military in Brazilian politics. This march was organized by Ipes and made clear the extension of the power of the coup groups and the fear of the middle class with the reforms and with the social movements that sprang up across the country.

Read too:Church and the Military Dictatorship in Brazil

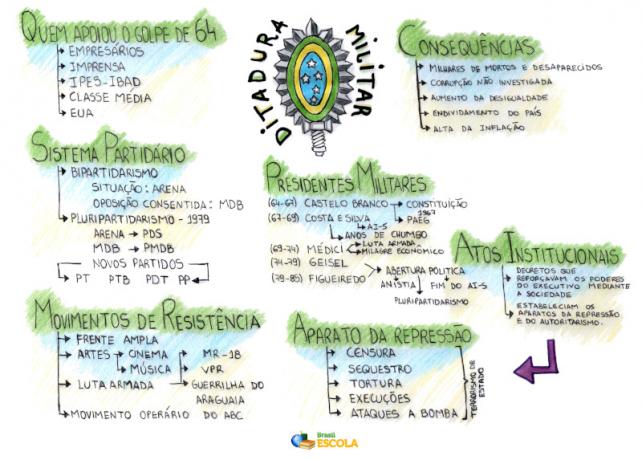

Mind Map: Military Dictatorship

*To download the mind map in PDF, Click here!

The coup against João Goulart was organized to take place around the 10th of April, in a joint action by the military, members of Ipes and the USA (the Americans organized themselves from Operation Brother Sam), but things did not turn out as foreseen. On March 31, a rebellion organized by Olympio de Mourão started the civil-military coup.

Olympio Mourão was the commander of the 4th Military Region and started a rebellion in Juiz de Fora. His troops marched towards Rio de Janeiro with the aim of overthrowing the government. The Mourão rebellion had the support of the governor of Minas Gerais, Magalhães Pinto, and, at first, it was viewed with suspicion by members of the Armed Forces, such as Castello Branco.

During these events, João Goulart remained totally inert and took no effective action to detain the military who marched against his government. The groups on the left were waiting for a superior order for possible resistance, but that order never came. Jango was aware that the ongoing coup had US support and knew that a resistance would start a civil war – a possibility rejected by the president.

Jango's great ally in the army, Amaury Kruel, withdrew his support from Jango, which placed him in isolation and removed the possibilities of internal resistance within the ranks of the Armed Forces. While the military marched against the government, Brazilian parliamentarians decided to act and, on April 2, 1964, Auro de Moura, Senator of the Republic, declared the presidency of the Republic vacant and opened the way for the Military Junta to take over the power of the Brazil. On April 9th, the Institutional Act No. 1 and the Military Dictatorship in Brazil began to take shape.

Grades

1 SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz and STARLING, Heloísa Murgel. Brazil: A Biography. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015, p. 441.

2 NAPOLITANO, Marcos. 1964: History of the Brazilian Military Regime. São Paulo: Context, 2016, p. 46.

3 Idem, p. 50.

4 Idem, p. 47.

5 SKIDMORE, Thomas E. Brazil: from Getúlio to Castello. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2010, p. 306.

6 GASPARI, Elio. The embarrassed dictatorship. Rio de Janeiro: Intrinsic, 2014, p. 49.

Image credit

[1] Evandro Teixeira/Moreira Salles Institute

By Daniel Neves

Graduated in History

Source: Brazil School - https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/historiab/golpe-militar.htm