Wars in modernity: nationalism and imperialism

The period from the beginning of the AgeModern (16th century) until the formation of the nationalisms and imperialisms of the nineteenth century brings together a vast succession of wars, especially because it is during this period of time that the process of globalization began, that is, the integration of all the continents of the globe terrestrial. From the point of view of wars, we can divide this long period into two main phases:

1) From the 16th to the 18th century, when wars had three main factors, which are as follows: (1) the eminently aristocratic, as the territorial definition of the absolutist kingdoms; (2) those that implied divergences between the overseas colonies and their respective metropolises (Thewar for independence of the United States, for example, occurred in the second half of the 18th century); and finally, (3) the factors that implied conflicts of interest between the European metropolises, as was the case with the conflicts between the Portuguese and the Spanish against the Dutch in the 17th century.

2) From 1789 to 1870, when there was the advent of war models different from those of the Ancien Regime. These models had their notorious development during the RevolutionFrench and the warsNapoleonic and, later, they grew with the formation of nationalist states, of which the processes of German and Italian unification and the processes of independence in Hispanic America are major examples. It is noteworthy that the Franco-Prussian War, arising from the UnificationGerman, was the last great European war before the First World War and that the great wars throughout the history of the American continent also took place in the nineteenth century: the Warfrom Paraguay and the WarCivilAmerican.

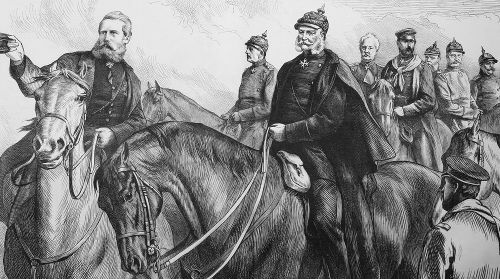

King of Prussia on the battlefield with his generals

typology of conflicts

From the first division we made above, we can list the main conflicts, separating them into three topics based on the themes we highlighted. Are they:

1) the eminently aristocratic: War of Austrian Succession, War of Spanish Succession, War of the Polish Succession, Thirty Years War and Seven Years War;

2) those that implied divergences between the overseas colonies and their respective metropolises: War of Emboabas, Balaiada War, War of the cabins, Guaranitic Wars, Tejucopapo Battle, the boston tea party and the United States War of Independence;

3) the factors that implied conflicts of interest between the European metropolises themselves: Luso-Dutch War.

With regard to the second phase of our division, which begins with the French Revolution, it is important to make it clear that the wars that followed this revolution are “daughters”, in large part, of the Revolution Industrial. Therefore, their main feature was a gigantic modernization, both in terms of armaments and infrastructure. Furthermore, they are wars with a strong “totalizing” bias, that is, they are part of “total mobilizations”, which involve almost the entire society and not just members of the aristocratic army. Starting from this idea, there are historians who defend that the Napoleonic wars, and not the FirstWar World, they actually made up the “first total war”.

One of the most prominent supporters of this thesis is David Bell, who underscores the uniqueness of this type of war and its relationship to the Industrial Revolution. If in the Napoleonic wars the carnage was already tremendous due to the evolution of armaments, a hundred years later, the First War would reveal something even worse. Says Bell:

So the language that justified the fighting, including the language of 'war to end all wars', had a real effect. On battlefields profoundly transformed – in relation to Napoleonic fields – by the Industrial Revolution, this language stimulated armies Europeans to persist in a carnage that Napoleon himself, despite his contempt for the 'life of a million men', could never to imagine.[1]

GRADES

[1] BELL, David. Total War I – Napoleon's Europe and the birth of international confrontations as we know them. (trans. Miguel Soares Palmeira). Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2012. p.422.

By Me. Cláudio Fernandes