GilbertoFreyre was one of the most important sociologists in Brazil, having built a work entirely dedicated to analysis of social relations in Brazilian colonial period and how these relationships contributed to the formation of the Brazilian people in the 20th century. His prominence was given for defending a theory that miscegenation would form a better and stronger population, contrary to what the theories thought. ethnocentric, hygienists and eugenics of nineteenth- and twentieth-century anthropologists and intellectuals.

While it was common at the time to think that there should be racial purity, Freyre goes against it saying that miscegenation is positive. However, his work, despite having an anti-racist basis, contributed to the criticism of anti-racist movements for having formulated a kind of myth of racial democracy in colonial Brazil and in republican Brazil, pointing to miscegenation as the foundation for this ideology.

Read too: Emergence of sociology in Brazil and worldwide

Biography of Gilberto Freyre

Brazilian anthropologist and sociologist Gilberto Freyre was born in the city of Recife, Pernambuco, on March 15, 1900. From a traditional family in Recife society, his father, Alfredo Freyre, was a teacher, lawyer and judge. Freyre studied at the former Colegio Americano Gilreath, now Colegio Americano Batista, a traditional educational institution run for some time by his father. Freyre emerged early as a talent for the literature and the human sciences. While still in high school, the sociologist participated as editor and editor of the newspaper O Lábaro, produced by Colégio Americano Gilreath.

Freyre studied sociology, but not in Brazil, as the first higher sociology course in the country had not yet been founded, which only happened in 1933. in 1918 the intellectual left for the United States, where he studied, at Baylor University, a BA in liberal arts and a specialization in political and social sciences. At Columbia University, Freyre pursued a master's and doctoral degree in political, legal and social sciences, defending his doctoral thesis entitled Social life in Brazil in the mid-19th century.

In the 1920s, he returned to Brazil after his studies in the United States and several trips around Europe, he also returned to live in Recife. in 1926 participated in the formulation of theManifestRegionalist, contrary group to 1922 Modern Art Week, of nationalistic character. The regionalists were against the “swallowing” of European culture to formulate a Brazilian culture, defended by the modernists, valuing only what was originally Brazilian.

Between 1927 and 1930, Freyre was Chief of Staff of the Governor of Pernambuco, Estácio Coimbra, and, in 1933, in political exile provoked by the 1930 revolution and with the arrival of Getulio Vargas to power, he published his most famous book: Casa Grande and Senzala. In 1946 he was elected constituent federal deputy. Freyre received several awards and doctorates honoris causa and was awarded the title of knight of the british empire, awarded by Queen Elizabeth II of England.

Do not stop now... There's more after the advertising ;)

What did Gilberto Freyre stand for?

Freyre went against almost all anthropological theories that emerged in the nineteenth century through intellectuals like Herbert Spencer. Classical anthropological theories were ethnocentric and advocated the supremacy of the white “race” over others. Brazilian politicians and intellectuals brought such ideas of “racial purity” to Brazil and tried, in the beginning of the 20th century, a “whitening” of the Brazilian population as a proposal for the improvement of society.

For Gilberto Freyre, the miscegenation was positive. As a scholar of anthropology, Freyre was a supporter of the theories of the German anthropologist, based in the United States, Franz Boas. Boas argued that the culture of a people should be studied not in comparison with the anthropologist's own culture, but with an immersion of that professional in that culture as if he were part of it. This would allow the scholar to look at it closely and without prejudice.

For Freyre, colonial Brazil presented a society that mixed and integrated Africans, Indians and whites, and that was what would have formed a stronger race, more intellectually capable and with a more elaborate culture.

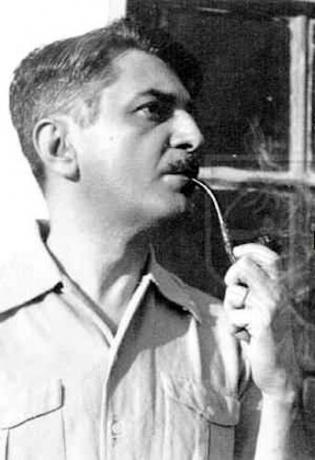

![Gilberto Freyre still receives harsh criticism for the concept of racial democracy. [1]](/f/038a3f8f7f9f954c005425c8c7de5d5e.jpg)

Theoriesby Gilberto Freyre

Gilberto Freyre's most widespread theory permeated all of his work. In big house and slave quarters, it began to be discussed, although it has not yet been uttered. It was the theory of racial democracy, criticized by defenders of the fight against racism for presenting itself as a myth that there was democracy in the relations between masters and slaves in the colonial period. For Freyre, miscegenation was a corroborative factor for thinking about a democratic relationship between masters and slaves, despite the bond of slavery impregnated between the two.

Read more: Black movement: fight against racism and for the social equality and rights of black people

Casa Grande and Senzala

The work Casa-Gande and Senzala went to Gilberto Freyre's most widespread, being translated into more than 10 languages. The writing of the book began at a time when the author went into exile in Portugal, due to the political divergence with the new government of Getúlio Vargas, which came to power with a coup in 1930.

In Casa-Gande and Senzala, Freyre tried to get away from the obvious in social analyses.: politics, economy, society in general. He preferred to delve into other themes: domestic life, family constitution, formation of the large houses (where the masters lived whites) and senzalas (where the blacks lived), to understand the sugar mill and rural property as the centers of Brazil colonial.

One mystification that Freyre helped to promote, perhaps through the influence of his professor of anthropology at Columbia, was that of that the miscegenation and geographic location of Brazil (in the tropical line) were negative factors that put the country in a lower position than Europe. The theory of racial democracy is an ideological mystification that Freyre, unfortunately, helped to build based on the mistaken idea that the relationship between masters and slaves was peaceful, that the Indians accepted colonization peacefully and that this promoted a democratic relationship and miscegenation.

This Freyrean vision, despite having some value for understanding colonial life in Brazil, does not materialize. Current analysis on the social inequality, even truly associate inequality and exclusion with the social issue. Perhaps Freyre's starting point that led him to formulate the theory of racial democracy (and which was the racial relationship explicitly segregationist in the United States) has led him to perceive a racial democracy in Brazil because there is a milder relationship between black and white.

However, veiled and structural racism never ceased to exist here, and the social inequality shows itself as a factor strongly provoked by slavery and by the relationship of submission to which blacks and Indians were forced by the white man. Therefore, the main thesis of Casa-Gande and Senzala it does not seem to hold up, while the book is an interesting tool for understanding the everyday life of colonial society.

Quotes by Gilberto Freyre

“Knowledge must be like a river, whose fresh, thick, copious waters overflow the individual and spread out, quenching the thirst of others. Without a social purpose, knowledge will be the greatest of futility.”

"Nowhere in Brazil has the formation of the family proceeded as aristocratically as among sugarcane fields."

"Cooking is one of the greatest expressions of human behavior, human knowledge, human creativity, a lot of human knowledge is in what you eat."

“Brazil is the most advanced racial democracy in the world.”

“From the cunhã, the best of indigenous culture came to us. Personal cleanliness. The hygiene of the body. The corn. The cashew. The porridge. The Brazilian of today, a lover of bathing and always with a comb and a little mirror in his pocket, his hair shiny with lotion or coconut oil, reflects the influence of such remote grandparents.”

Image credit

[1] Public domain / National Archives Collection

by Francisco Porfirio

Sociology Professor