THE Proclamation of the Republic happened on the day November 15, 1889 and it was the result of an articulation between military and civilians dissatisfied with the monarchy. There was dissatisfaction among the military with salaries and careers, in addition to demanding the right to express their political positions (something that had been prohibited by the monarchy).

There was also discontent among emerging elites with under-representation in the politics of the monarchy. Groups in society began to demand greater participation through elections. The abolitionist question also added strength to the republican movement. These groups united in a coup that toppled the monarchy and expelled the royal family from Brazil.

Accessalso: A summary of the main events of the First Republic

monarchy in crisis

The Proclamation of the Republic, in November 15, 1889, was the result of a long process of crisis of the monarchy in Brazil. The monarchic regime began to fall into decay soon after the end of the

Paraguay War, in 1870, which resulted from the inability of the monarchy to meet the interests and demands of Brazilian society.A series of new actors and new political ideas emerged and gained strength through the republican movement, officially structured from 1870, when the republican manifesto. Around republican ideas, a consistent group was formed that organized a coup against the monarchy in 1889.

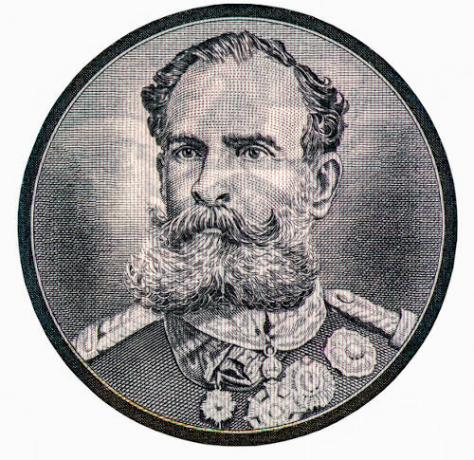

![The crisis of the monarchy led civilians and military to organize a coup to overthrow the monarchy, on 15 November 1889.[1]](/f/c43a7d9daf76c4bfff3e306fb018d2a4.jpg)

Political disputes and the consolidation of the Army as a professional institution are two important factors in this crisis of the monarchy. The demand for the modernization of the country made many civilians and military people see the repúpublic the solution for the country, as the monarchy began to be regarded as incapable of existing demands.

Do not stop now... There's more after the advertising ;)

Military

THE military dissatisfaction it is directly related to the professionalization of the corporation. After that, they began to demand improvements in their careers in recognition of their services in Paraguay. The main requirements were salary and promotion system improvements.

Another strong dissatisfaction is related to the Brazilian Army's involvement in politics. The military understood themselves as tutors of the Brazilian State and, therefore, wanted to have the right to publicly express their political opinions. A symbolic case occurred in 1884, when official Sena Madureira was punished for showing support for Ceara's abolitionists.

The monarchy also sought to censor the military, prohibiting them from expressing their opinions in newspapers and in military corporations. There were also demands among the military for Brazil to become a parentssecular. Internally, military grievances have rallied around the positivist ideology.

From positivism, the military began to claim the idea that the modernization that Brazil needed would take place through a governmentrepublicandictatorial. Thus, they believed that it was necessary to choose a ruler who would lead the country on the path of modernization and, if necessary, that ruler could depart from the popular will.

Read too: What is military intervention?

politics and society

The policy in second reign it has always been complicated, especially by the fierce fight between conservatives and liberals. crisis of underrepresentation of some provinces. In the second half of the 19th century, the country's economic axis had consolidated its shift from the Northeast to the Southeast.

The province of São Paulo had already positioned itself as the great economic center of Brazil, but the political elites in that province were bothered by the fact that their representation in politics was little. Other economically decaying provinces, such as Rio de Janeiro and Bahia, enjoyed great political representation.

This situation alienated the elites of that province with the monarchy, and this helps us to understand, for example, why the province of São Paulo had the largest republican party of the Second Reign, the Republican Party of São Paulo (PRP).

there was also under-representation of society in the political system. Cities grew and new social groups established themselves. These emerging groups demanded greater participation in Brazilian politics, and the path taken was the opposite. Liberals advocated widening the vote to weaken conservatives and big farmers, but conservatives managed to pass the LawHail, in 1881.

This law established new criteria for stipulating who would be entitled to vote and, after its approval, the number of voters in Brazil fell from 1,114,066 people to 157,296 people|1|. This corresponded to only 1.5% of the Brazilian population, that is, the demands for participation were not met and the existing exclusion was increased.

These new elites began to occupy political spaces in other ways and expressed their opinions through newspapers, associations and public demonstrations in defense of causes such as the laic State|2|. This dissatisfaction with the problems of the monarchy obviously reinforced the republican cause in the country.

In 1870, the ManifestRepublican, a document that criticized the centralization of power in the monarchy and demanded a federalist model in Brazil (a model that gives autonomy to the provinces). This manifesto also attributed responsibility for the country's problems to the monarchy and indicated the republic as the solution. The manifesto was a guide for the republican movement at the end of the Empire.

Another cause that greatly reinforced the republican movement was the defense of abolition. O abolitionism it mobilized Brazilian society in the 1880s, and a large part of the abolitionists defended the republic.

In general, sociologist Ângela Alonso summarizes that the Brazilian monarchy was structured on the following tripod:

- restricted political participation;

- slavery (and exclusion of the African element); and

- Catholicism as defender of social hierarchies|2|.

The 1870s and 1880s came to question this tripod, as there were demands for greater participation social, abolitionism required the insertion of blacks in society and secularism sought to establish a society lay.

Also access: See how tenentism shook the First Republic in Brazil

Proclamation of the Republic

There were then dissatisfactions with the monarchy in different layers of our society. Emerging elites, military, politicians, popular classes, slaves were all groups with criticisms of the monarchy. All these dissatisfactions, sometime in the 1880s, became a conspiracy.

![One of the first actions of the November 15 coup was the agglomeration of troops under the leadership of Deodoro da Fonseca in Campo do Santana.[2]](/f/65c7a058cef477d80e40dc007748807b.jpg)

Throughout that decade, public demonstrations began to become commonplace, and criticism of the emperor grew. An attack on the emperor's car in July 1889 motivated the Empire to prohibit public demonstrations in defense of the republic, but Brazil was on a path of no return, as the group of dissatisfied was very large.

By November 1889, the conspiracy was underway and had names like AristidesWolf, BenjaminConstant, QuintinoBocaiuva, RuiBarbosa, solonbrook, between others. What the conspirators lacked was the adhesion of the marshal Deodoro da Fonseca, an influential military man and the first president of the Clube Militar.

On November 10, supporters of the coup against the monarchy met with Deodoro to convince him to take part in the movement. In the following days, the rumors that a conspiracy was underway began to gain traction, and on the 14th, false information about the monarchy began to be announced in public with the aim of enlisting supporters.

O coup against the monarchy followed on the 15th, when Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca and troops went to the headquarters located in Campo do Santana. was required to Dismissal of the Viscount of Ouro Preto of the presidency of the ministerial cabinet. The Viscount resigned and was arrested by order of Deodoro da Fonseca.

Meanwhile, the marshal was waiting for the emperor to organize a new cabinet, so he cheered D. Pedro II and then returned to his home. The overthrow of the cabinet did not end the events of the 15th, and political negotiations followed. Republicans decided to hold an extraordinary session at the Rio de Janeiro City Council to hold a solemnity of Proclamation of the Republic.

THE Proclamation of the Republic took place in the Chamber, being announced by councilor José do Patrocínio. There was a celebration in the streets of Rio de Janeiro, with those involved in the proclamation cheering the republic and singing A Marseillaise (a revolutionary song produced during the French Revolution) on the streets of the capital.

During this turn of events, an attempt at resistance was organized under the leadership of André Rebouças and Conde d'Eu, husband of PIsabella, but this resistance failed. The emperor D. Pedro II he remained confident that the situation would be easily resolved, but that was not how it happened.

One governmentprovisionalwas formed, O Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca he was nominated as president of Brazil (the first in our history) and others involved in the coup assumed important positions in the government. THE royal family was expelled on November 16, and the following day, they embarked with their goods for the city of Lisbon, in Portugal.

Accessalso: How many coups d'etat have there been in Brazil since independence?

What were the consequences?

The Proclamation of the Republic radically changed Brazilian history. National symbols and new heroes were exchanged, such as Tiradentes, were established. In addition to the change in the form of government, Brazil became a nation with powerdecentralized, as the federalism. Changes took place in the electoral system, as the census criterion was abandoned, and universal male suffrage for men over 21 was established.

Brazil became a statesecular, it's the presidentialism became the system of government. The organization of the republic took shape when a new constitution in the year 1889. The 1890s were marked by a period of dispute between republicans and royalists and deodorists and florianists.

Grades

|1| LESSA, Renato. The republican invention: Campos Sales, the bases and the decadence of the First Brazilian Republic. Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks, 2015, p. 73.

|2| ALONSO, Angela. Establishment of the Republic in Brazil. In.: SCHWARCZ, Lilia M. and STARLING, Heloisa M (eds.). Dictionary of the Republic: 51 critical texts. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2019, p. 165.

Image credits:

[1] commons

[2] FGV/CPDOC

By Daniel Neves

History teacher