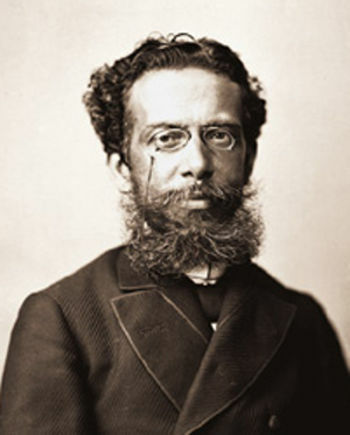

Gonçalves Dias (Antônio Gonçalves Dias) was born on August 10, 1823, in Caxias, Maranhão. He was the son of a white Portuguese and a Brazilian descendant of Indians and blacks. He later studied law in Portugal at the University of Coimbra. Back in Brazil, in addition to publishing books, he worked as a professor and, in addition, was appointed an official in the Foreign Affairs Secretariat.

The poet, who died on November 3, 1864, in a shipwreck, it's part of first generation of romanticism Brazilian. His works, therefore, have Indianist and nationalist elements, as can be seen in his poems exile song and I-Juca-Pirama. Furthermore, her texts have a theocentric character and realize the idealization of love and women.

Read too: Maria Firmina dos Reis – 19th century Brazilian romantic writer

Gonçalves Dias (Antonio Gonçalves Dias) was born on August 10, 1823, in Caxias, in the state of Maranhão. His father was the Portuguese merchant João Manuel Gonçalves Dias. His mother, Vicencia Mendes Ferreira, from Maranhão. Thus, the father was white, and Vicencia, “Mestiza of Indians and blacks”, according to the Doctor of Letters Marisa Lajolo.

The author's parents were not married, and when João Manuel married another woman in 1829, he took their son to live with them. Then the writer was literate in 1830, and three years later he went to work in his father's store. Years later, in 1838, the young Gonçalves Dias left for Portugal, where he studied Law at the University of Coimbra.

Back in Brazil, he moved to Rio de Janeiro in 1846. That same year, your play Leonor de Mendonça was censored by the Dramatic Conservatory of Rio de Janeiro. As early as 1847, he was appointed to work as secretary and professor of Latin at the Liceu de Niterói.

Do not stop now... There's more after the advertising ;)

In 1849, he became a professor of Brazilian History and Latin at Colégio Pedro II. Two years later, in 1851, he traveled to the North, on an official basis, to analyze public education in that region. That same year, he intended to marry Ana Amélia Ferreira do Vale (1831-1905), but the girl's mother did not give her consent.

This is because the poet, as he himself wrote in a letter to the girl's brother, had no fortune and, “far from being a blue-blooded nobleman”, was not even a legitimate son. In addition, there was the racial issue, which, it seems, also weighed in the decision of Ana Amélia's mother.

Thus, the author began an unhappy marriage, in 1852, with Olímpia Coriolano da Costa. This year, assumed the position of official of the Secretariat of Foreign Affairs. Then, between 1854 and 1858, he worked at the Europe, in the service of the secretary, and, during this period, he separated from his wife in 1856.

During the years 1859 and 1862, was part of the Scientific Exploration Committee, who traveled by North and North East of Brazil. However, in 1862, he decided to return to Europe for treatment, as he had tuberculosis. Two years later, when he returned to Brazil, suffered a shipwreck and died on November 3, 1864.

Read too: José de Alencar – great name in Brazilian romantic prose

Gonçalves Dias is an author of the first generation of Brazilian Romanticism. He wrote poems Indian in character, in which the indigenous is the central element, and also nationalist, for praising Brazil. In this way, every Indianist poem by the author is also nationalist, since the indigenous is seen as the national hero.

However, not every nationalist poem is Indianist, as is the case with exile song, where it is not possible to point out the figure of the Indian, but only bucolicism, when the lyrical self refers to elements of Brazilian nature. It is noteworthy that romantic nationalism is boastful, that is, not critical, but just uplifting.

The local color, that is, the geographic and cultural characteristics of the Brazilian territory, is also present in the author's poetry. In this case, we are talking about the forest and indigenous culture, but we must not forget that the romantic Indian is just a Brazilian symbol. Therefore, it is idealized and not realistic, so that, in most cases, it is associated more with bourgeois values than with indigenous ones.

Finally, both in Indianist poetry and in loving-lyrical poetry, the love theme is present,associated with female idealization. Furthermore, since Romanticism takes up medieval values, loving suffering and a theocentric perspective are imprinted in the romantic poet's verses.

![Cover of the book I-Juca-Pirama, by Gonçalves Dias, published by the publisher L&PM.[1]](/f/c664165ee957da3d9c2e3b471ca5e2b0.jpg)

patkull (1843) — theatre.

Beatriz Cenci (1843) — theatre.

first corners (1846) — Indianist and lyrical-loving poetry.

Meditation (1846) — prose.

Leonor de Mendonça (1846) — theatre.

Agapito's Memories (1846) — prose.

second corners (1848) — Indianist and lyrical-loving poetry.

Friar Antao's sextiles (1848) — poems of a historical and religious character.

Boabdil (1850) — theatre.

last corners (1851) — Indianist and lyrical-loving poetry.

the timbiras (1857) — Indian epic poem.

See too: 5 best poems by Fernando Pessoa

The poem "green leaf bed", from the book last corners, is composed of decasyllable verses (ten poetic syllables), uncommon during the Romanticism, but consistent with the narrative character of the poem. In him, O me lyric is an indian woman waiting for her beloved, Jatir, for a night of love. She is in the woods, where she made a bed of leaves to be with her lover. However, he does not arrive, and the day dawns:

Why delay, Jatir, what a cost

Does the voice of my love move your steps?

From the night the turning moving the leaves,

Already at the top of the woods it is rustling.

Me under the canopy of the haughty hose

Our gentle bed zealously covered

With beautiful soft-leaf tapiz,

Where the limp moonlight plays among flowers.

[...]

The flower that blooms when dawn breaks

A single turn of the sun, no more, vegetates:

I'm that flower I still wait

Sweet ray of the sun that gives me life.

[...]

My eyes other eyes never saw,

Did not feel my lips other lips,

No other hands, Jatir, other than yours

The arazoia in the belt squeezed me.

[...]

Don't listen to me, Jatir; don't be late

To the voice of my love, which calls you in vain!

Tupan! there the sun breaks! of the useless bed

The morning breeze shakes the leaves!

Already in the poem "time urges”, also from the book last corners, the lyrical self speaks of the passage of years, which brings change in nature. However, according to the poetic voice, the human spirit, over time, acquires greater brilliance. Furthermore, she states that affection does not change, does not end, but grows with time:

Time is urgent, the years go by,

Eternal change the toilsome beings!

The trunk, the shrub, the leaf, the flower, the thorn,

Who lives, who vegetates, takes

New looks, new shape, while

Rotates in space and balances the earth.

Everything changes, everything changes;\

The spirit, however, as a spark,

Which goes on undermining and hidden,

At last it becomes fire and flames,

When he breaks the dying rags,

Brighter shines, and to the skies I can drag

How much he felt, how much he suffered on earth.

Everything changes here! only affection,

Which is generated and nurtured in big souls,

It doesn't end, it doesn't change; keeps growing,

As time increases, more strength increases,

And death itself purifies and makes it beautiful.

Like a statue erected among ruins,

Firm at the base, intact, more beautiful

After time has surrounded her with damage.

The poem “Song of exile” from the book first corners, is a symbol of Brazilian romantic nationalism. The work is composed in a larger round (seven poetic syllables), a type of verse often used in Romanticism. Written when the author was studying in Portugal, in 1843, the poem reflects the longing that Gonçalves Dias felt for his homeland. Thus, the work praises Brazil by stating that there is no better place than that country:

My land has palm trees,

Where the thrush sings;

The birds, which chirp here,

It doesn't chirp like there.

Our sky has more stars,

Our floodplains have more flowers,

Our forests have more life,

Our loves more life.

In brooding, alone, at night,

More pleasure I find there;

My land has palm trees,

Where the thrush sings.

My land has primes,

Such as I do not find here;

In brooding alone at night

More pleasure I find there;

My land has palm trees,

Where the thrush sings.

Don't let God let me die,

Without my going back there;

Without enjoying the primes

That I don't find around here;

Without even seeing the palm trees,

Where the thrush sings.

Image credit

[1] L&PM Editors (reproduction)

by Warley Souza

Literature teacher