Carolina Mary of Jesus was a writer from Minas Gerais born on March 14, 1914. Despite having only two years of formal study, she became a writer and became nationally known in 1960 with the publication of her book Eviction Room: Diary of a Favela, in which she reported her daily life in the Canindé slum, in Sao Paulo city. Died on February 13, 1977. Today she is considered one of the most important black writers gives literature Brazilian.

your bookstorage room brings the memories of a black and slum dweller (as the subtitle says) who saw writing as a way out of social invisibility where she found herself. With her diaries, her memories recorded through writing, Carolina Maria de Jesus gave meaning to her own history and today she is an essential figure in Brazilian literature.

Read too: The representation of blacks in Brazilian literature

Biography

the writer Carolina Mary of Jesus was born in the city of Sacramento, Minas Gerais, on the day March 14, 1914. Daughter of a poor family, she had only two years of formal education. From 1923 to 1929, the family of farmers migrated to Lajeado (MG), Franca (SP), Conquista (MG), until returning permanently to Sacramento. In that city, the writer and her mother were imprisoned for a few days. As Carolina knew how to read, the authorities concluded that she read to do witchcraft.

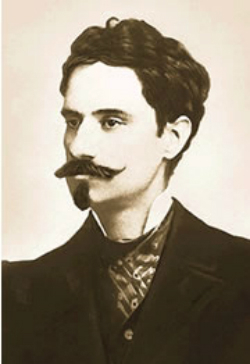

![The writer Carolina Maria de Jesus, in 1960. [1]](/f/3ee591a2dd21351fdf70fc2ee71eedad.jpg)

In 1937, Carolina Maria de Jesus moved to the city of São Paulo, where she worked as a maid. In 1948, she went to live in Canindé slum, where their three children were born. While she lived there, her livelihood was pick papers and other materials to recycle.

In the midst of all this difficult reality, there were books. Carolina Maria de Jesus was in love with reading. Literary writing, therefore, was a consequence. So, in 1950, she published a poem in honor of Getulio Vargas, in the newspaper The defender. In 1958, the journalist Audalio Dantas (1929-2018) met the author and discovered that she had several notebooks (diaries) in which she gave her testimony about the reality of the favela.

Do not stop now... There's more after the advertising ;)

It was he who helped the writer to publish her first book — Eviction Room: Diary of a Favela. So, in 1960, the book was published and became a bestseller. That same year, the author received honors of the Paulista Academy of Letters and the Academy of Letters of the Faculty of Law of São Paulo, in addition to receiving an honorary title gives Order Caballero del Tornillo, in Argentina, in 1961.

![Carolina Maria de Jesus autographing her book Quarto de espejo, in 1960. [1]](/f/42516f139244cfea37b7e64d6752c30a.jpg)

After the success of her book, Carolina Maria de Jesus moved from the Canindé favela, she recorded an album with her own compositions and continued to write. However, her next works were not as successful as the first. In 1977, on the day February 13th, Carolina Maria de Jesus died in Parelheiros, a district of the city of São Paulo.

Read too: Black Literature - literary production whose subject of writing is black himself

Main works

Carolina Maria de Jesus' work is markedly memorialistic, one testimony literature, in which the author exposes the reality in which she lives and reflects on it. From this perspective, his main books are:

- storage room (1960);

- Brick house (1961);

- Bitita Diary (1986);

- my weird diary (1996).

The book that was most successful was Storage room, but this did not happen again. You next booksdid not arouse interest neither from the critics nor from the Brazilian press. The author began to fall by the wayside. But in the year before her death, in 1977, her first book was re-released by the publisher Ediouro. In 1986, almost ten years after his death, your posthumous work, Bitita Diary, was published in Brazil. However, this book had already been published, in 1982, in Paris, with the title: Bitita's Journal.

![Cover of the book Diário de Bitita, by Carolina Maria de Jesus, published by SESI-SP. [2]](/f/7c15d1a57410004f424ce225cd83f969.jpg)

It was in 1994 that the book Black Cinderella: the saga of Carolina Maria de Jesus, by José Carlos Sebe Bom Meihy and Robert M. Levine, was published and generated a new interest in the writer. The following year, the same authors launched, in the United States, the book The life and death of Carolina Maria de Jesus. Also, they organized the books. my weird diary and personal anthology, composed of texts left by the author and published in 1996.

The book storage room is the masterpiece of Carolina Maria de Jesus. It has been translated into several languages. Currently, about 40 countries know this work. After the author's death, this book continued to be edited, Carolina Maria de Jesus became the name of the street and library, she had books produced about her and many academic dissertations and theses were written mainly about her first work. The author, therefore, conquered a prominent place in literature and national history.

According to Fernanda Rodrigues de Miranda, master in Letters: “Carolina Maria de Jesus is the forerunner of Peripheral Literature in the sense that she is the first Brazilian author of breath to establish the weaving of her word from experiences in the space of the favela, that is, Her narrative brings the peripheral everyday not only as a theme, but as a way of looking at oneself and the city. Therefore, her gaze becomes increasingly critical in the face of the illusions that São Paulo projected with its false image of a place with opportunities for everyone”.

See too: Women and Brazilian Poetry

➔ storage room: diary of a slum dweller

![Cover of the book Quarto de espejo, by Carolina Maria de Jesus, published by Ática publishing house. [3]](/f/39b48b374913665ad3837a2a1bbdbdad.jpg)

The book storage room, by Carolina Maria de Jesus, is the author's diary written from 1955 to 1960. In it, the first thing that stands out is the language, closer to colloquial, without worrying about grammatical rules, which makes the work truer, closer to reality.

Carolina Mary of Jesus I really liked to read. This made a difference in her life, as she became a world-renowned writer and, through writing, he was able to leave the favela context. For her, reading was something necessary and, despite the misery in which she lived, she always found a way to continue with this habit: “I picked up a magazine and sat on the grass, receiving the sunbeams to warm me up. I read a short story. When I started another one, the children came asking for bread”.

Her portrait of the Canindé favela is raw, straight, untouched: “During the day, 15 and 18 year olds sit on the grass and talk about theft. And they've already tried to rob Mr. Raymundo Guello's emporio. And one was stamped with a bullet. The robbery started at 4 o'clock. When day broke the children collected money in the street and in the grass. There was a child who collected twenty cruzeiros in currency. And smiled showing off the money. But the judge was strict. He punished mercilessly”.

The author is the slum voice and it performs the function of showing this reality, in her diary, as violence against women and the situation of children in this environment: “Silvia and her husband have already started the show in the open air. He is beating you. And I am disgusted with what the children witness. They hear bad words. Oh! if I could move from here to a more decent nucleus”.

Her diary is also a instrument of resistance and justice, the author believes in the power of the written word, in the power of literature. On one occasion, Carolina Maria de Jesus goes to a butcher shop, where the cashier refuses to sell her anything. Later, the author writes: “I went back to the favela in a rage. So the favelado's money has no value? I thought: today I'm going to write and I'm going to swear at the disgraceful box at the Bom Jardim Açúgue”. And she fulfills her promise: “Ordinary!”.

Furthermore, she is aware that her writing can change your life: “It's just that I'm writing a book, to sell it. With this money I intend to buy land for me to leave the favela. I don't have time to go to anyone's house”. However, she was not understood by her neighbors: “José Carlos heard Florenciana say that I look crazy. That I write and earn nothing”. Or: “A shoemaker asked me if my book is communist. I replied that it is realistic. He told me that it is not advisable to write the reality”.

Another interesting fact of the author's life is her option not to marry, which shows an independent and strong woman for her time: “I face any kind of work to keep them [the children]. And they have to beg and still be beaten. He looks like a drum. At night, while they ask for help, I quietly listen to Viennese waltzes in my shed. [...]. I don't envy the married women of the favela who lead the lives of Indian slaves.”

This independence of his is also manifested in this excerpt: “Mr. Manuel appeared saying that he wants to marry me. But I don't want it because I'm already mature. And then, a man is not going to like a woman who cannot get by without reading. And that he gets up to write. And that he sleeps with pencil and paper under the pillow. That's why I prefer to live only for my ideal”.

for being a strong personality woman, Carolina Maria de Jesus, in the context of the work, is not much appreciated by the other women in the favela. But writing (in addition to reading) is the way the author finds to support the problems of her reality: “Here, everyone teases me. They say I speak very well. That I know how to attract men. When I get nervous I don't like to argue. I prefer to write. Every day I write. I sit in the backyard and write”.

The reference to the reading and how important she is in the writer's life: “I spent the rest of the afternoon writing. At half past four, Mr. Hector turned on the light. I bathed the kids and got ready to go out. I went to get some paper, but I was unwell. I left because the cold was too much. When I got home it was 22.30. I turned on the radio. I took a shower. I heated up food. I read a little. I can't sleep without reading. I like to handle a book. The book is man's best invention”.

Another element that is repeated in the diary is the mention of hunger: “I went to the market on Rua Carlos de Campos, to pick up something. I gained a lot of vegetables. But it had no effect, because I don't have fat. The boys are nervous because they don't have anything to eat”. And yet, on the anniversary of the signing of the Golden Law, Carolina Maria de Jesus wrote: “And so on May 13, 1958 I struggled against current slavery — hunger!”.

In fact, Audálio Dantas, the journalist who introduced Carolina Maria de Jesus to the world, made the following statement about this: “Hunger appears in the text with an irritating frequency. Tragic, unstoppable character. So big and so striking that it acquires color in Carolina's tragically poetic narrative”.

And, by experiencing hunger, the author demonstrates the awareness of social inequality when he criticizes the government at the time: “What Mr. Juscelino [Kubitschek] has of usable is his voice. He looks like a thrush and his voice is pleasant to the ear. And now, the thrush is residing in the golden cage that is Catete. Sabeiá be careful not to lose this cage, because when cats are hungry they contemplate the birds in the cages. And the favelados are the cats. You are hungry”.

So, rholds the government accountable for poverty: “When Jesus said to the women of Jerusalem: — 'Don't cry for me. Weep for you — his words prophesied the government of Mr. Juscelino. Pain of hardships for the Brazilian people. Too bad that the poor will have to eat what they find in the garbage or else sleep hungry”.

Not only is the president of Brazil the target of his criticisms, as we can see below: “Politicians only appear here during electoral periods. Mr. Cantidio Sampaio, when he was a councilor in 1953, spent Sundays here in the favela. He was so nice. Drank our coffee, drank from our cups. He addressed us with his viludo phrases. He played with our children. He left good impressions here and when he ran for congressman he won. But in the Chamber of Deputies he did not create a project to benefit the favelados. He didn't visit us anymore”.

besides your conscience as a woman and a slum dweller, she is also aware of prejudices and racial discrimination: “I was paying the shoemaker and talking to a black man who was reading a newspaper. He was angry with a civil guard who beat a black man and tied him to a tree. The civil guard is white. And there are certain whites that turn black into a scapegoat. Who knows if the civil guard doesn't know that slavery has already been extinguished and that we are still under the whip?”.

When he goes to pick up papers offered by a lady, who lives in a building, going up the elevator, barefoot, on the sixth floor, “the gentleman who entered the elevator looked at me with disgust. I am already familiar with these looks. I don't grieve”. Then the well-dressed man wants to know what she is doing in the elevator. She explains herself and asks if he's a doctor or a deputy, he says he's a senator.

Lastly, Carolina Maria de Jesus justifies the title of her book: “the Police still haven't arrested Promessinha. The insane bandit because his age does not allow him to know the rules of the good life. Promessinha is from the Vila Prudente favela. It proves what I say: that favelas do not form character. The favela is the eviction room”. And also: “I classify São Paulo like this: the Palacio, it's the living room. City Hall is the dining room and the city is the garden. And the favela is the backyard where garbage is thrown”.

The book storage room it is marked, as it became clear, by a very critical view of reality. The author Carolina Maria de Jesus does not refrain from talking about politics, the situation of black and slum women in society, and hunger. His work, besides literary (and a declaration of love for reading and writing), carries a strong political load, so that it is not possible to separate one perspective from the other. Thus, when she writes that the favela is the eviction room, the author makes clear her indignation at the reality in which she lives.

Image credits:

[1] National Archive / Public Domain

[2] Sesi-SP Publisher / Reproduction

[3] Editora Ática / Reproduction

by Warley Souza

Literature teacher